To jazz followers, however, it meant the arrival of Jamaican alto saxophonist, Joe Harriott and other modern musicians who rode the wave of emigration to find professional opportunities in England.

However, Harriott and his fellow-travellers were not the first to do this. The music of the Pre-War jazz age became a major form of popular music via dance bands, and this was due to an earlier influx of Caribbean jazz musicians who had enriched the British swing scene.

To jazz followers, however, it meant the arrival of Jamaican alto saxophonist, Joe Harriott and other modern musicians who rode the wave of emigration to find professional opportunities in England. er, Harriott and his fellow-travellers were not the first to do this. The music of the Pre-War jazz age became a major form of popular music via dance bands, and this was due to an earlier influx of Caribbean jazz musicians who had enriched the British swing scene.

Most of these earlier jazz pioneers were linked to the ill-fated late-1930s dance orchestra of Ken Johnson, considered by many to be the ‘swingiest’ swing band in Britain.

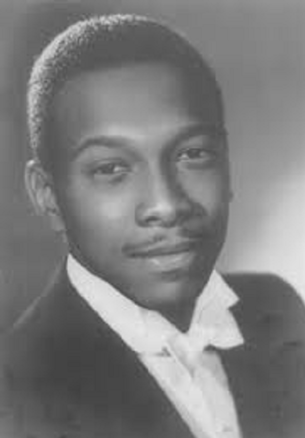

Ken Johnson

Just prior to the start of Johnson’s career , the Jamaican-born Leslie Thompson was a prominent London-based 1930s jazz and stage musical trumpeter, who played in Louis Armstrong’s 1934 European band. It is no surprise he was hired by the American jazz legend, for he had by that time built his reputation in the pit orchestras of many high-profile West End stage musicals, bringing them a contemporary credibility.

Just prior to the start of Johnson’s career , the Jamaican-born Leslie Thompson was a prominent London-based 1930s jazz and stage musical trumpeter, who played in Louis Armstrong’s 1934 European band. It is no surprise he was hired by the American jazz legend, for he had by that time built his reputation in the pit orchestras of many high-profile West End stage musicals, bringing them a contemporary credibility.

One of his contacts was the African-American choreographer, Buddy Bradley, who had already taught Fred Astaire and other Hollywood screen dancers. That dancing and jazz were linked was not lost on him and he longed to unite the two.

Thompson was further influenced by Marcus Garvey, who had been deported from America and, although known as the 20th century’s first important pan-Africanist, was no stranger to the music business himself, having written an American hit, Keep Cool. By the 1930s Thompson was well aware of Garvey’s messages, delivered frequently at Speakers Corner in Hyde Park, and his British newspaper, The Black Man. Consequently Thompson was inspired to form an all-black dance band and, although there were African-American jazz musicians who frequented Europe, his ideal ensemble would be a solely West Indian one.

By coincidence, the Guyanese student, Ken Johnson’s first show business aspiration was London cabaret dancer. The lure of the Jazz Age drew him to study tap dancing with Buddy Bradley, and between 1934-1935 he went to the United States where he studied this art and mastered film star Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson’s stairs-dance routine.

Like Leslie Thompson’s Garvey-inspired dream, Ken Johnson, now known as ‘Snakehips’, saw that all-black swing-jazz success need not be limited to the United States. He returned to the Caribbean, where he formed a touring band with prominent musicians including the Barbados trumpeter Dave Wilkins, the Trinidad clarinettist Carl Barriteau and fellow Trinidadian saxophonist, Dave ‘Baba’ Williams, all of whom would later feature prominently at a key juncture in Johnson’s career.

In January 1936, Johnson went to England to further his dream. While he had been abroad his tap-and-shuffle dance had been well received in the1935 film, Oh Daddy!. Johnson needed a seasoned musician, a so-called ‘straw boss’, to rehearse the group, and the real work was done by Leslie Thompson, who worked hard to form the band.

Alto/tenor sax and clarinet star Bertie King, alto sax and clarinet expert Louis Stephenson, fellow saxophonist Joe Appleton, trumpeter Leslie ‘Jiver’ Hutchinson and pianist Yorke de Souza were all from Jamaica. Trumpeter Wally Bowen arrived from Trinidad, the alto sax and clarinet specialist Robert Mumford-Taylor’s father was from West Africa, guitarist Joe Deniz moved down to London from Cardiff, double-bassist Abe ‘Pops’ Clare was also from the Caribbean. Another bassist, Bruce Vanderpoye, was a South African, and drummer Tommy Wilson was from Birmingham.

Thompson said he could only find one good Black trombonist when he was forming the Ken Johnson-fronted orchestra. However, the Black British musician, possibly Ellis Jackson , who also sang both conventionally and with Negro stereotype dialect in the Billy Cotton band, wouldn’t go on tour.

But this difficulty was overcome in the Johnson Orchestra . After all, despite their contrasting backgrounds they were foremost a Black British band working in white Britain.

Like white musicians, Black jazz players were drawn to London by the opportunity to play in small nightclub bands but the Black artists could not get work in the white bands. A typical place of work was The Nest Club, which was frequented by Black performers from visiting American jazz attractions such as The Mills Brothers and Fats Waller.

Generally musicians who made up the house bands in such niteries received up to £5 a week for their work, a reasonable rate, but not stable employment. As a result the Black musicians found that having their own orchestra was a more secure means of employment.

The ‘Snakehips’ Johnson Orchestra

So the ‘Snakehips’ Johnson Orchestra, co-led with Leslie Thompson was born in the spring of 1936, touring cinemas and other venues throughout the country. By early 1937, the Orchestra was playing at the Old Florida Club in the West End, owned and managed by the former Duke Ellington Orchestra vocalist, Adelaide Hall. Thompson earned at least £20 per week but, although he was the original backer and practical organiser of the group, Johnson and his manager legally formalised a joint ownership of the Orchestra with the result that Thompson was cut out of any financial interest. This took place just as the Orchestra was being scouted by a BBC producer for broadcasts.

Many of the players resigned in support of Thompson and the Orchestra would have been decimated, but Ken Johnson retained Jiver Hutchinson and he had already made overtures to other musicians in the Caribbean. The quality newcomers, Barriteau, Wilkins, and Williams, were summoned to Britain and sailed on banana boats. These strong players helped maintain the Johnson Orchestra’s reputation as superlative swingers.

The Johnson Orchestra’s BBC radio programmes, broadcast from the Café de Paris, could not have happened at a better time. The night spot was a magnificent, expensive supper club, featuring an oval, mirrored room with a spacious dance floor. A pair of curved staircases surrounded the bandstand and, from these, the exclusive clientele entered the basement premises.

In 1999, the British Library Sound Archive received a collection of Johnson’s 1938 radio broadcasts. No doubt Ken Johnson understood that singers added variety to his Orchestra’s show, but he only hired a female singer for BBC broadcasts, as the Corporation then had a requirement for two vocal numbers per half hour of such programming.

The commercial disc issues made for British Decca (1938) and HMV (1940) were just that: an attempt to reach the generic buyers of dance band records. The British record industry was not ready to categorise Ken Johnson and His West Indian Dance Orchestra as a jazz market act, but rather as a mainstream dance band.

On 8 March 1941 the Snakehips Johnson Orchestra was still holding down the prestigious and lucrative spot at The Cafe de Paris, when London suffered aerial bombardment and the club suffered two direct hits. While some musicians were seriously injured, Ken Johnson, saxophonist Dave ‘Baba’ Williams and many of the club’s dancers died in the attack. Read about the arrangements made for Johnson’s funeral and correspondences with his mother about his memorial service.

The Orchestra, of course, dispersed but most musicians were hired by various white bandleaders. Carl Barriteau, Leslie ‘Jiver’ Hutchinson, Dave Wilkins, Joe Deniz and the Birmingham drummer, Tommy Bromley, all appeared on the famous November 1941 ‘First English Public Jam Session Recording’, held at the Abbey Road studios. Some of the musicians made private recordings and there were a few small group sessions that were issued commercially, such as those by the Cyril Blake’s Jigs’ Club Band and the Spirits of Rhythm Sextet. This was led by Joe Deniz’s brother, Frank, who was also a guitarist. ‘Jiver’ Hutchinson eventually revived the all-Black big band concept, which toured throughout the 1940s. His daughter, jazz vocalist Elaine Delmar, became a favoured star of Ronnie Scott’s Club in Soho.

Fortunately a number of Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson’s major players were interviewed in their later years for the British Library Sound Archive’s Oral History of Jazz in Britain Project. These recordings are available for study in the Listening Service at the Library. Such life stories complement the Library’s holdings of periodicals documenting the era, such as the Melody Maker, many jazz-specific publications, and the BBC’s own Radio Times. The Humanities 2 Reading Room also provides information on vintage commercially-issued discs by way of record company catalogues, the Gramophone, and the like.

The surge of Post-War Caribbean immigration would later enrich the London jazz milieu, with the arrival of Jamaican-born alto saxophonist, Joe Harriott, guitarist, Ernest Ranglin, and the St Vincent-born trumpeter, Shake Keane, among others. But it was the pioneering black British swing artists who set the stage for the stars of more recent times.