But Gayle, better known as first black footballer in Liverpool’s 89-year history, was born in Toxteth and spent many of his teenage years knocking around on Granby Street – a gritty melting pot of a community south of Liverpool’s city centre.

A Liverpool supporter, he followed the team home and away as a self-confessed football hooligan before he emerged from the terraces as a first team player. Howard later joined Birmingham City, taking in spells at Sunderland and Blackburn Rovers also. He now lives back in Liverpool’s south end, on the streets where he spent his earliest years.

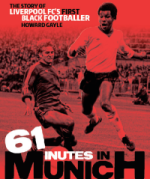

Gayle who has just released is autobiography, 61 Minutes in Munich talks to Black History Month about his life in the city of Liverpool during one of the most turbulent periods in its history.

Your autobiography, 61 Minutes in Munich, is released in October. Why now?

Circumstance. I’ve been working on this project for more than six years. There have been one or two complications along the way. I just feel that now is the right time; the right moment. I wanted it to be right for me, my family and my friends. And I think it is.

A big theme in the book is the issue of race. How much of an impact do you think race had on your life?

What I am today is a consequence of what has happened to me in the past. I had difficulties growing up with institutions affecting my path along the way and how I view life: the education system, the judicial system and even Liverpool FC. I’ve experienced inequality. It shapes who you are. The bad experiences and the good experiences contribute towards the personality of who I am today: how I see life, how I see people and how they judge me.

Do you think your football career would have been different at Liverpool had you been in a working environment where you weren’t in the minority?

Yeah, maybe it would have been. As a 19-year-old entering a famous institution, you are always conscious of your surroundings anyway, regardless of race. It was a club that I’d supported – a club that I loved. I’d experienced inequalities on the terraces supporting Liverpool throughout the 1970s and perhaps that helped prepare me for what was to come to a certain extent…

As Liverpool’s first black player, were you conscious that you were making history, though?

No. There were other black players at Liverpool. It wasn’t something we spoke about. There was Stevie Cole and Lawrence Iro playing in the A and B teams, though they didn’t go as far as I did. I made my Liverpool debut against Manchester City and on that day, nobody mentioned that I was the first black player. It was only when I left Liverpool that historians looked back and realised the significance.

What kind of issues did you have to face that maybe others did not?

I remember my brothers telling me that I’d have to be twice as good as the white people to make it as a footballer. Perhaps that was true. First of all, as a footballer, you always have to convince the decision makers at the club that you can play football. That never stops. But I felt there was more focus on me to see whether I could handle the pressure of playing football – and more importantly, playing football for what was considered one of the greatest sporting institutions. Liverpool was a juggernaut in English and European football. As the first black player, some people at Liverpool didn’t understand the black culture. If they’d have known a little bit more about me and understood a lot of the challenges that I needed to go through to get to where I was, then maybe I’d have had a bigger role in the club’s history. Instead, I only made a small contribution. I felt I had more to offer. I trained with world class every single day and didn’t feel out of place. In the end it was a big decision to move away from a club and a city that I loved. But it was something I had to do.

Liverpool’s growth as a city is linked to the empire isn’t it – more than people care to recognise?

Yes. I’m from Toxteth and you only have to look around there to understand the impact it had and the wealth it generated. Liverpool grew strong through its links with West Africa and the Caribbean and the distribution of cotton, sugar and other commodities. That was only made possible because of the slave trade. Liverpool became a major port as a result of many unfortunate people suffering.

There are issues in isolation covered the book that many people will be able to relate to. Yet your story when all of those issues are placed together is quite unique…

There are stories in the book that I’ve had to live with my whole life without being able to tell anyone for a number of reasons. I’d rather people bought the book to read them in their full context instead of detailing them here. When readers arrive at the end of the book, I hope they have a better understanding of who I was then and who I am now. All the way through my football career, for example, it was said that I had a chip on my shoulder. It was a criticism levelled at other black players too. If that’s the case, then it’s there for a reason: due to attitude and treatment. I’d like this book to enlighten people and help them understand the issues that I have faced and why they have affected me.

In August, you rejected an MBE because of the empire’s links to the slave trade…

All of the reasons for this are explained in the book. But the stand-out issues behind my reasoning, I’ve made clear. The slave trade is a part of my history, my upbringing and my culture. I don’t see why I should move on and ignore what has happened in the past. My ancestors would turn in their grave. What happened was appalling. I also think about the Hillsborough disaster and how the establishment treated the affected families and the city of Liverpool. Through political machinery, they tried to blame Liverpool people and capitalise on the stigma that existed. It was a smear on the people of Liverpool. In my opinion, the establishment had not forgotten what happened during the Toxteth riots of 1981 and this was their opportunity to condemn the city.

*Howard Gayle’s 61 Minutes in Munich (deCoubertin) will be available from October.

TITLE 61 Minutes in Munich

AUTHOR Howard Gayle

ISBN13 978-1-909245-39-6

PRICE £16.99

BIC CODE WSJA

RPT CODE NP