Marshall Street was an unassuming, unexceptional street in Smethwick, in the west Midlands. Its terraced houses were not particularly striking or notable and the declining industrial town it stood in, resembled many others across the country, facing a myriad of social and economic challenges. But Marshall Street was at the centre of a thick hostile local and national race row, which called into question the very nature of what it meant to be British.

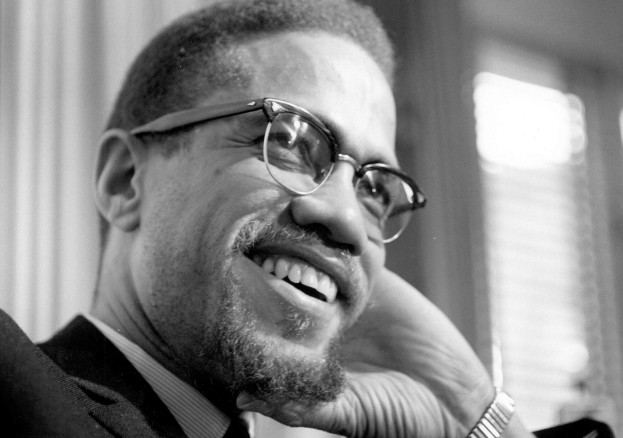

A visit by Civil Rights activist, Malcolm X, in February 1965, just before his death, ensured that the struggles centred around this Street went global and Smethwick was thrust into the international spotlight.

Smethwick’s recent history was intimately associated with racism and white supremacy. As the constituency of former British Union of Fascists leader, Oswald Mosely, the shadow of his hateful politics hung over the town, even as it diversified in the years following the war. Smethwick had an immigrant population of 6.7%, a small figure but significantly higher than the national average of 1%. This substantial immigrant population was contested by large sections of the town’s white residents, whose image of a white British nation was challenged. More recently, the parliamentary election for the Smethwick House of Commons seat had been embroiled in bitter racism. Conservative Peter Griffiths won the vote from the incumbent Labour candidate, as dissatisfied residents and voters organised around the slogan: “if you want a n****r for your neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour”. When confronted about the vile phrase, Griffiths defended it as a “manifestation of popular feeling”.

Griffiths’ ties to Marshall Street were deeper than the hotly contested 1964 election. As part of the Smethwick Council, he had been at the centre of plans to essentially implement segregation on the streets of Britain. A campaign by many of the white residents on the racially diverse street lobbied for the government to buy up the remaining houses and reserve them only for white residents. The so-called Marshall Plan, intended to make Marshall Plan a white only street, implementing US Jim Crow-style segregation on where people could live.

Malcolm X’s visit to the UK was an eclectic, fast-paced trip to notable locations and some of Britain’s largest Black communities. As Graham Abernathy writes, he arrived “eager to explore and publicise the social and political barriers faced by Black people living in Britain” and to “foster transatlantic” cooperation. After a visit to Oxford, which included talking at the Oxford Union, and a stay in London, Malcolm X voyaged outside of these arguably unsurprising locations, into the English midlands, arriving in Smethwick on 12th February.

An invitation from the Indian Workers Association, a group formed to mobilise and represent migrants from the Indian subcontinent in the late 1930s, had brought Malcolm X to Smethwick. The intense racism and discrimination faced by both the Black and South Asian communities had caught his attention. In journeying to Smethwick, Malcolm X ventured outside of what may be considered unsurprising locations for his visit (Oxford, as an intellectual centre, and London as the capital and the home to a large and visible Black community) into, what Joe Street of the University of Kent describes as “the heart of England” into, arguably, the country’s “most racist locality”.

Arriving in Smethwick, Malcolm X enjoyed considerable time with members of the local branch of the IWA. The significance of the interracial cooperation his association with the IWA signalled, is further explored by Joe Street, who argues it is symptomatic of Malcolm X’s changing views on racism and anti-racism cooperation. Street writes, Malcolm X’s philosophy, once focused uniquely on the Black American experience, had altered after his travels to Africa and Mecca in 1964, to advocate for “the need for minorities to unite around their minority status, rather than their (specific) racial identity”. Thus, in meeting with and cooperating with the IWA and Smethwick’s South Asian population, Malcolm X was actively promoting solidarity between the Black and South Asian communities in the face of white British racism. Previously active in the Nation of Islam (NOI), which focused mainly on mobilising Black Americans specifically, Malcolm X’s ideology and view of interracial cooperation and solidarity had significantly changed over the course of his travels, leading him to break from the NOI in 1964. His visit to, and actions in Smethwick, fit into this story of ideological change and his split from the NOI, which would have profound consequences for him and the Civil Rights movement more generally.

Malcolm X made a series of striking comments during his time in Smethwick, directly attacking and challenging British racism. Asked why he would choose to visit Smethwick of all places, he replied: “I have heard that the Blacks…are being treated in the same way as the Negroes were treated in Alabama-like Hitler treated the Jews”. Drawing a line between the racism in the US and the horrors of the Holocaust, still well within living memory of many of the residents of Smethwick, Malcolm X exposed British racism for exactly what it was. For white Brits who remembered the war and the suffering enacted through the Holocaust, these comments, perhaps shockingly, equated their actions and motives with those of Hitler and the Nazi regime, casting British racism in a resolute and unflinching manner. He also cautioned the Black and South Asian population in Smethwick not to wait for the “fascist element” in the town to erect “gas ovens” before it organised itself.

Most notably, Malcolm X made a point of walking down Marshall Street. The ordinary, rows of terraced housing, caught up in an attempt to introduce social segregation, stood by as one of the most notable Civil Rights activists in the world strode past them. Chairman of the local IWA branch, Avtar Singh Johal recalled, in conversation with Al Jazeera, that Malcolm X had asked to spend time on the street, talking to residents and inspecting the racist signs on the street, which doubtless included placards repeating the common refrain: No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs. This visit to Marshall Street was followed by a trip to the Blue Gates Pub, where Malcolm X, Singh Johal and other IWA members and Black residents were told to leave on account of their race and skin colour.

His visit was met with fierce criticism and derision, from those who insisted the ‘race problems’ in England, America and elsewhere were fundamentally different. Griffiths retorted that, “Smethwick rejects the idea of being a multi-racial society”. He went on to pedal segregationist policies, including advocating for children of Indian descent to be taught separately from white British children and housing segregation, until he lost his seat to the Labour candidate in the 1966 election. Yet, for the community of Colour in Smethwick, Malcolm X’s visit had put their daily struggles and ongoing fight against British racism into the spotlight.

Two weeks later in the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, New York, Malcolm X was shot dead by an individual associated with the NOI. His actions in the last few weeks of his life, spanned countries and continents, linking up Smethwick, an ordinary and unexceptional British town, with the likes of Harlem, one of the most famous Black communities in the US. Malcolm X’s visit to Smethwick and the West Midlands, though brief, was of insurmountable importance in pushing back against the prevailing racist culture and highlighting the importance of solidarity and cooperation in the fight against racism in Britain.

Sources

- Abernathy, ‘“Not Just an American Problem”: Malcolm X in Britain’, Atlantic Studies, Vol.7, No.3, pp.285-307, (3 September 2010)

- Buettner, ‘“This is Staffordshire not Alabama”: racial geographies of commonwealth immigration in early 1960s Britain’, The journal of imperial and Commonwealth history, vol.42, no.4, pp.710-740, (2014).

- Goodwin, ‘If you want a n****r for your neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour’, New African, pp.40-42, (Oct., 2004).

- Pitts, ‘Malcolm’s Journey to England to organise Blacks there’, New York Amsterdam News, Vol.84, No.2, p.32, (9 Jan, 1993).

- Street, ‘Malcolm X, Smethwick and the Influence of the African American Freedom Struggle on British Race Relations in the 1960s’, Journal of Black Studies, Vol.38, No.6, pp.932-950, (Jul., 2008).