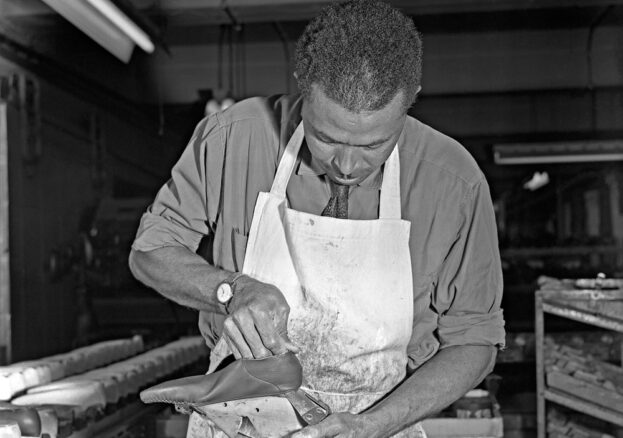

In a Leicester shoe factory in 1959, a worker bends over a half-stitched moccasin, the light catching the curve of the leather as he guides it into shape. The rhythm of the workshop surrounds him: the thud of presses, the pulsing of stitching machines, the low murmur of workers concentrated on their tasks. The air carries the industrial scent of polish, adhesives and freshly cut hide. To the casual observer, it is an ordinary industrial scene. Yet within its ordinariness lies one of the most profound social shifts in Britain’s modern history. His hands, steady and practised, belong to a generation whose labour quite literally helped rebuild post-war Britain.

When the Second World War ended in 1945, Britain emerged victorious but exhausted. Cities bore the scars of Luftwaffe bombing. Housing stock was depleted. Transport networks were strained. Whole sectors of the economy — from textiles to steel to heavy industry — were suffering from severe labour shortages. The government quickly realised that demographic recovery would take decades. Between 1945 and the mid-1950s, British employers repeatedly warned ministers that output could not be sustained with the existing workforce. The Ministry of Labour’s own reports carried stark language: “Production targets cannot be met without additional labour from the Commonwealth.” Britain needed workers, and it needed them urgently.

Into this gap stepped thousands of men and women from the Caribbean, travelling on British passports as citizens of the Empire and later the Commonwealth. They arrived with expectations shaped by years of schooling under British colonial curricula: images of Britain as the “Mother Country,” a place of opportunity, stability and belonging. Many came believing that they would be welcomed, and that their skills and labour would help build a fairer, more prosperous nation. The reality they found was more complex — a mixture of opportunity and hostility, necessity and exclusion — but their contribution would reshape Britain’s workforce and its social landscape.

Leicester’s footwear industry was one of the many sectors that depended on their arrival. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the Midlands had been the beating heart of the British shoemaking trade. Towns such as Northampton, Kettering, Market Harborough and Leicester formed a production belt renowned across the world. In the late 1950s, Leicester alone employed more than 23,000 workers in its footwear factories. Despite the introduction of mechanised cutting and stitching machines, shoemaking remained a craft rooted in human skill. Every stage — from clicking the hide to shaping the upper, from pegging and lasting to double stitching — demanded precision, muscle memory and a level of craftsmanship that machines could not replicate. National output exceeded 180 million pairs of shoes a year, a figure that was impossible to maintain without a consistent and reliable workforce.

By the mid-1950s, Britishborn workers were increasingly leaving factory floors for clerical, retail or administrative jobs. Manufacturers struggled to fill vacancies. It was in this context that Caribbean migrants, many of whom had trained in trades, agriculture or skilled manual work back home, became indispensable. Local recruitment efforts often spread by word of mouth: a friend already in Leicester might write home saying that the shoe factories were hiring, that shifts were steady, and that the wages — while modest — offered stability. For newly arrived migrants, this stability mattered. Leicester’s factories became both workplaces and gateways into British life.

The worker in the 1959 photograph — his attention fixed on the moccasin in his hands — represents a generation whose contribution is far larger than any single moment captured on film. His careful movements remind us that the post-war recovery was not built in urgent political speeches or grand architectural projects but in thousands of repetitive, highly skilled acts carried out day after day. It was the quiet steadiness of this labour, often overlooked and under-acknowledged, that enabled Britain to meet production demands, sustain export markets and keep its industries competitive.

Oral histories held in the East Midlands Oral History Archive provide vivid testimonies from the era. One Caribbean-born factory worker, reflecting on his early years on the production line, recalled: “Britain needed workers, and we came. We kept the lines moving when no one else would.” His words cut through the myth that migrants merely filled low-skilled gaps; they reveal a truth essential to the national story. Without the Windrush generation, Britain’s industrial output would have faltered in the very years it sought to rebuild its economy and international standing.

Yet the work was far from easy. Many migrant workers encountered racism both inside and outside the factory. Some were given the dirtiest or most repetitive jobs, often with little chance of advancement. Pay disparities were common, and union representation was inconsistent. Securing housing in Leicester could be even more challenging: landlords frequently refused to rent to Black tenants, forcing new arrivals into overcrowded and poorly maintained lodgings. Despite these systemic barriers, communities formed. Churches, social clubs and community gatherings became essential networks of mutual support, resilience and cultural continuity.

The Windrush generation’s contribution extended far beyond the industrial floor. Their presence held up the expanding National Health Service, which was itself struggling to fill thousands of nursing, midwifery and support roles. It kept buses and trains running in cities like London, Birmingham and Bristol, where transport authorities actively recruited in the Caribbean. It supported steelworks, engineering plants, textile mills and other pillars of British industry. Britain’s welfare state — celebrated today as a cornerstone of post-war democracy — could not have functioned without their labour. A nurse who arrived in the 1950s, reflecting decades later in an interview recorded by the King’s Fund, simply said, “We helped to make this country strong again.” The power of that statement lies in its understatement. It speaks to work done without applause, service provided without expectation of reward.

Leicester itself was transformed by these arrivals. Neighbourhoods in Highfields, Belgrave and other districts grew into vibrant centres of Black British life. Children of the factory workers walked to school past the very workshops where their parents stitched and shaped shoes. Those children — and their children — would go on to become business owners, councillors, teachers, artists, athletes and community leaders. The cultural landscape of Leicester began to change: Caribbean food, music, language and traditions found new homes, weaving themselves into the social fabric of the city.

This photograph, then, is not just an image of a man making a shoe. It is a window into a moment when Britain was being reshaped by people whose contributions rarely appeared in official histories. His hands guided leather into form, but they also helped guide Britain into a new era. They remind us that the making of a modern nation was not only the work of statesmen and planners but of immigrants who believed enough in Britain’s promise to give their labour, their families and their futures to it.

Sixty years later, the factory floor has fallen silent. Many of the companies that once defined Leicester’s industrial strength have closed. But the legacy of those who worked there has not faded. Leicester today is one of the most diverse cities in the United Kingdom, its vibrancy inseparable from the communities built by the Windrush generation. Their story is not one of marginal presence but of central importance. The man in the photograph is not merely performing a task of industrial routine; he is helping to craft the Britain we know today — stitch by stitch, day by day, generation by generation.

References & Further Reading

- UK Government, “Celebrating the Windrush Generation” – overview of who the Windrush generation are and their contribution to Britain.

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/celebrating-the-windrush-generation GOV.UK - East Midlands Oral History Archive (EMOHA), University of Leicester – collections including migrant experiences and work in Leicester.

General archive page: https://le.ac.uk/emoha University of Leicester

Learning resource on migration to Leicester: https://le.ac.uk/emoha/learning/migration University of Leicester - The King’s Fund, “You called and we came: Windrush and the NHS” – oral histories and reflections from Windrush-generation NHS staff.

https://features.kingsfund.org.uk/windrush-and-the-nhs/ features.kingsfund.org.uk - English Heritage, “The Story of Windrush” – historical background on the Empire Windrush and post-war migration to Britain.

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/the-story-of-windrush - UK Government, Windrush Monument & Education Resources – materials on the Windrush story and its significance in British history.

Windrush Monument education resources: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/windrush-monument-education-resources - East Midlands Oral History Archive digital collection – over 700 recordings covering work, migration and everyday life in Leicester and the East Midlands.

https://leicester.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15407coll1 - Black History Month (UK), “You Called and We Came: Remembering Nurses of the Windrush Generation”, Laura Serrant – on the vital role of Caribbean nurses in the NHS.

https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/the-windrush-generation/called-came-remembering-nurses-windrush-generation/