The article said that it took 13 years for the victim to be recognised as a legal citizen. During this period, the victim’s mother had passed away in the Caribbean and with great sadness the victim said, “The worst thing that has happened to me in my entire life was that my mother passed away and I wasn’t with her. She worked in factories, she saved to bring me over. She taught me to read and write, when I was in trouble at school, she did everything for me. I haven’t been by her graveside.” In London, my mother also worked in factories and saved to bring me over.

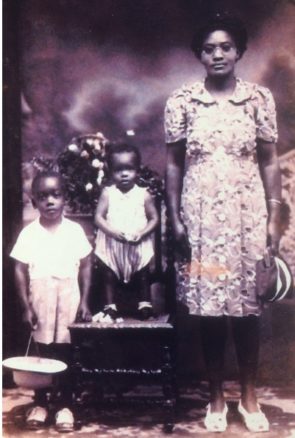

My father was a shoemaker. He left us and went to America when I was about ten years old. My mother never saw him again. She took my younger brother and I to live with her grand-aunt (Auntie) and eight sisters in Allman Town, Kingston. She had difficulties earning a living as a dressmaker. In early November 1951, when I was eleven years old, about the age my mother left school, one of my aunts woke me and said, “Your mother is going to England, get up and see her get the ship…” We dismounted from Mr Green’s truck at Port Antonio. I remember waving to her as the ship sailed away. She waved back from the top deck of the ship which was loaded down with people and green bananas. Recent research by a friend, Marjorie Morgan, has informed me that my mother sailed on the Ariguani in 1951, not the Mauritania as I was told as a child. Her passenger status was British.

I did not see my mother again until 1955. I was fourteen years and eleven months old. It took her four years to save my fare to ‘bring me over’. The fare was £86. I disembarked from the Ascania at Liverpool and took a train to Paddington. I wormed my way along a platform full of people until a ‘woman’ grabbed me by the shoulder and said, “I am your mother, come with me.” I would not have recognised her but when I looked into the mirror, we resembled each other. She took me home to a house in North London. Every room contained a family of at least two people. Marjorie’s research also shows that my mother had registered me on the passenger list of my ship as a Scholar.

However, after arriving on the 2nd March 1955, my mother woke me early on the 3rd March and told me she had secured me a job working in a grocer’s shop which delivered lunches. My mother needed help with the rent. Her wages were less than £5 per week and the rent for her single room was about half this sum.

As we were about to leave the house at about 7.45 am, a man stopped us and asked my mother where we were going, my mother said that we were going to work. The man said to my mother, “You can go to work but he cannot. He is not yet fifteen years of age…the school leaving age in this country is fifteen” My mother stated that she could keep me at home until I was fifteen years of age…my fifteenth birthday was on the 9th April 1955. My mother argued that one month should not keep me away from work but the man was adamant, “I don’t make the rules, he has to go to school.” My mother relented and took me to a local Comprehensive School. The school concluded that I was ESN (Educationally Sub-Normal) and sent me to Shelburne Road Secondary Modern School. The great irony was that, unknown to me, my mother had registered me on the ship’s passenger list as a “Scholar”. Inadvertently, her actions started my ‘scholarly career’ outside her front door on the 3rd March 1955.

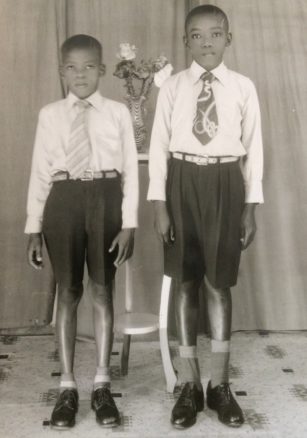

The Headmaster at Highbury Grammar School effected my transfer from Shelburne School to Highbury in September 1955. The Headmaster was interested in my cricketing skills. My mother was still keen on me working but agreed to the school transfer. She could not afford to pay for new uniforms and was pleased when Highbury Grammar offered her a few pounds. I shared my paper-round wages with her. She rented a larger room but after about two years the landlord give us notice to leave. We fought him in the magistrate’s court and won. We lived in the shadow of Pentonville Prison but not far from the Islington Library. I used the Library to keep warm and do my homework. The landlord turned our kitchen into a room and rented it. He locked the bathroom and my mother and I had to travel to a friend’s house to have a bath on Sundays. She cooked in our room on a paraffin heater and lost a job because she missed work after an operation. She never took her annual holiday and worked during this holiday period to double her income with her ‘holiday pay’.

I left Highbury Grammar in 1958, worked at Queen Elizabeth College as a technician and after a few rejections, I entered Leicester University in 1961. In 1964, when the only job I could find with an Honours degree in Botany was peeling potatoes in a nearby restaurant at Nags Head, my mother encouraged me to be patient. In December 1964 I was accepted for a PhD in Edinburgh, at the Heriot Watt University/Edinburgh University. I completed the PhD in 1967. My mother always knew where I was during my research-academic career…from 1968 to 2003, the year she passed away. She was the primary part of my sense of belonging. Although she never saw my father again after he left for America, when he died, she insisted that I should “go and bury him” in New York. I returned to the Heriot Watt University as a staff member in 1977. She used to ring the University and say, “Tell my son to call me, Miss Pennycook needs his advice”. Miss Pennycook was her Jamaican friend. Incidentally, there is a small town in Scotland called Penicuik…the old spelling was Pennycook! In passing, please note that this Scottish-Jamaican connection also extends to family names…for example, my mother’s surname was Larmond. The Scottish equivalent is Lamond. My cousin’s Scottish surname is Mowatt and another cousin was called, Gladstone Wood. Indeed, there are more Scottish Campbell surnames in the Jamaica telephone directory than are in the telephone directory of Edinburgh and surrounding areas.

When I gained my Doctor of Science degree my mother came to Edinburgh and powdered my face ‘to remove the shine’ before the photographs were taken . Later when I told her that the University had awarded me a Professorial Chair…she replied jokingly, “You have enough chairs in the house, tell them to give you more money!” Although most people called me Geoff, she called me Godfrey which is my real name. However, she would have been delighted to call me, Honorary Consul for Jamaica in Scotland. Her religious view regarding my ‘achievements’ was simple, “My son is just a vehicle…”

Family links were very important to my mother. She kept a notebook of the addresses of all members of the family. They called her Aunt Ivy. Friends called her, Miss Ivy. Grandchildren called her Nana or Grandma and I called her Mama. When she was very ill, I asked her to come to Scotland to live with me but she refused. She said that my brother needed her more. She was also aware that I had an interest in the history of British slavery in the West Indies. One day she told me that my middle name, Henry, came from our slavery ancestor whose only name was, Henry. Her father’s Christian name was Henry and she was pleased when I used my grain-research and teaching skills in Africa.

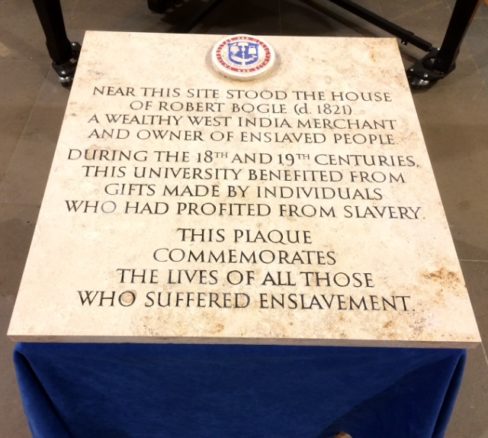

On the 23rd August 2019, I was given the great honour by Glasgow University of unveiling a plaque in the Chapel of the University to British enslaved people.

The marble plaque reads… “Near this site stood the house of Robert Bogle (d 1821). A wealthy West India merchant and owner of enslaved people. During the 18th and 19th centuries this University benefited from gifts made to individuals who had profited from slavery.

This Plaque commemorates the lives of all those who suffered enslavement”. Although this ‘reparative justice’ will benefit Caribbean and African students, this plaque is symbolic of the hopes of our ancestors come true. Paul Bogle (Morant Bay Rebellion, 1865) is a National Hero of Jamaica…both white Robert Bogle and black Paul Bogle have historical links with St Thomas, Jamaica…this coming together of history is important. Therefore, the action of Glasgow University is a first light which others should follow to help repair the consequences of chattel slavery which was the most profitable evil the world has known.

This Plaque commemorates the lives of all those who suffered enslavement”. Although this ‘reparative justice’ will benefit Caribbean and African students, this plaque is symbolic of the hopes of our ancestors come true. Paul Bogle (Morant Bay Rebellion, 1865) is a National Hero of Jamaica…both white Robert Bogle and black Paul Bogle have historical links with St Thomas, Jamaica…this coming together of history is important. Therefore, the action of Glasgow University is a first light which others should follow to help repair the consequences of chattel slavery which was the most profitable evil the world has known.

In the late 1990s my mother received a letter from the Home Office stating that if she did not apply to register, she would be deported. She threw the letter into the bin with disdain but I filled in the form and paid the fee. Like many of the ‘Windrush Generation’, she always treated racism with disdain…neither Enoch Powell nor Oswald Mosley bothered her. My mother was aware of her Jamaican-British historical connections. She was also aware that she and her ancestors had contributed ‘twice’ to Britain significantly…during slavery and during the Windrush period. She was too ill to accompany me to Buckingham Palace to receive my OBE (Order of the British Empire) award in 2003. However, she said, “You go get it for us…we made the Empire, and remember, wear your marina (vest) because ‘them places’ can be cold.”

Depending on how tired she was, she attended the church (black or white) that was closest to her home. She would sit reading her Bible. One day ladies from the local Greek Orthodox Church in Haringey asked me, “Is that dark lady your mother?” I nodded. They then asked, “Does she speak Greek?” I smiled and they smiled and said, “She is welcomed.” Before she sadly passed away in 2003, she said, smiling, “Make sure I am buried at home in Jamaica…it is too cold here.”

If we had a disagreement she would jokingly say, “Give mi back, what you can’t give mi back, mi £86!” She would then smile and say, “You see what a little hard work and the goodness of people can do.” Indeed, it was her love and support, a little hard work and the goodness of people that turned a ‘grocery boy’ into a ‘Scholar’. A sense of belonging and education go together to help people to give their best to society.

Some people say I was lucky but people’s lives should not be dependent on luck. To celebrate my mother’s life a plaque was placed in the George Square Garden of Edinburgh University. I often watch students and other people as they stand in front of my mother’s plaque and wonder why a mother called Mrs Ivy Georgina Larmond-Palmer, at rest in Jamaica, would be associated with the view that, ‘People are not just ‘races’, named and ranked by man, people are people’. For a distance I can hear my dear mother saying, ‘my son wrote that for everybody’.