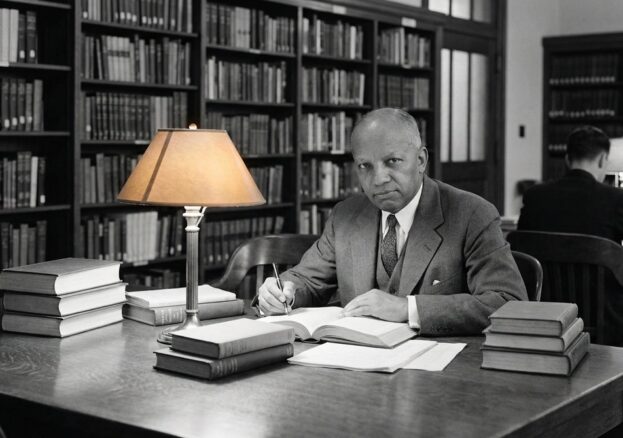

In the early decades of the twentieth century, when Black history was distorted, marginalised, or ignored entirely within American education, Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson set himself against the silence. He did not merely argue that Black history mattered — he built the institutions, scholarship, and frameworks that ensured it would endure. Woodson’s legacy is not confined to a single month or movement. It is embedded in the very idea that history should be truthful, inclusive, and shaped by those whose lives it records.

A Scholar Shaped by Exclusion

Carter G. Woodson was born in 1875 in Buckingham County, Virginia, to formerly enslaved parents. His early life was defined by poverty and labour; as a child, he worked in coal mines to support his family. Formal education came late and irregularly. Yet Woodson was driven by an intense intellectual hunger. Largely self-taught in his early years, he eventually attended high school in his twenties, completing the curriculum in just two years.

His academic ascent was extraordinary. Woodson earned degrees from Berea College and the University of Chicago before becoming only the second African American — after W.E.B. Du Bois — to receive a PhD from Harvard University. But prestige did not protect him from exclusion. Despite his credentials, Woodson found himself shut out of mainstream academic institutions, denied positions and platforms that his white contemporaries took for granted.

Rather than seeking acceptance, he chose independence — a decision that would define his life’s work.

Writing Black People Back into History

Woodson was deeply troubled by how history was taught. Textbooks routinely portrayed Black people as passive, inferior, or absent altogether. Where they did appear, it was often only in relation to enslavement, framed through white perspectives and priorities. Woodson understood that this absence was not accidental; it was a deliberate product of power.

In response, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) in 1915. Its mission was radical for the time: to research, preserve, and disseminate the history of people of African descent, told with scholarly rigour and pride. The following year, he launched The Journal of Negro History, creating a professional academic outlet when none existed.

Woodson believed that history was not simply about the past — it shaped self-worth, aspiration, and political possibility. A people denied knowledge of their achievements, he argued, would struggle to imagine their future.

The Birth of Black History Month

In 1926, Woodson introduced Negro History Week, choosing February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The intention was not symbolic tokenism, but strategic education. He envisioned schools, churches, and civic organisations using the week to study Black achievements across science, politics, culture, and resistance.

Crucially, Woodson never intended this focus to be limited to a single week. He saw it as a catalyst — a corrective to a curriculum that had long excluded Black contributions. Over time, Negro History Week expanded, eventually becoming Black History Month, officially recognised in the United States in 1976.

Today, Black History Month is observed across the world, including in the UK. While its form has evolved, its purpose remains rooted in Woodson’s original vision: to challenge historical erasure and affirm Black humanity through knowledge.

The Mis-Education He Warned Against

One of Woodson’s most influential works, The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), remains strikingly relevant. In it, he argued that education systems often trained Black students to accept inequality by internalising white supremacist assumptions. The problem, Woodson insisted, was not ignorance alone, but education divorced from truth.

He criticised curricula that celebrated European achievement while dismissing African civilisations, Black intellectuals, and resistance movements. For Woodson, education should be a tool of liberation, not accommodation.

His arguments continue to resonate in contemporary debates about representation in education, inclusive curricula, and whose knowledge is valued.

Independence Over Recognition

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Woodson remained sceptical of white patronage. He often funded his work personally, lived modestly, and resisted institutional control. This independence allowed him to publish uncompromising scholarship, but it came at personal cost. He worked relentlessly, often in isolation, and died in 1950 without widespread recognition.

Yet the movement he began outlived him.

The institutions Woodson built continue today under the name Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). His methods — archival research, community education, and historical self-determination — have influenced generations of scholars, teachers, and activists.

A Global Legacy

Although Woodson’s work was rooted in the African American experience, its implications are global. Across Britain, the Caribbean, Africa, and beyond, educators and historians have drawn on his ideas to challenge narrow national histories and reclaim suppressed narratives.

In the UK context, where Black British history has often been sidelined or treated as recent, Woodson’s insistence that history belongs to those who live it remains deeply relevant. His work reminds us that inclusion is not an act of generosity, but of justice.

Remembering Carter G. Woodson Today

Dr. Carter G. Woodson did not ask permission to tell the truth. He understood that history is not neutral — it reflects power, choice, and voice. By insisting that Black history be researched, taught, and respected, he changed not only what was known, but who was allowed to know it.

Black History Month, at its best, is not a pause from the curriculum, but a challenge to expand it. That challenge began with Woodson — a scholar who refused to let history forget.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson died on 3 April 1950, aged 74. His work continues to shape how Black history is studied and understood around the world.