History has a habit of simplifying innovation. It favours singular geniuses and neat origin stories — one inventor, one breakthrough, one decisive moment that changes everything. But the reality of technological progress is far more complex. It is collaborative, cumulative and often shaped by individuals whose names rarely appear in textbooks.

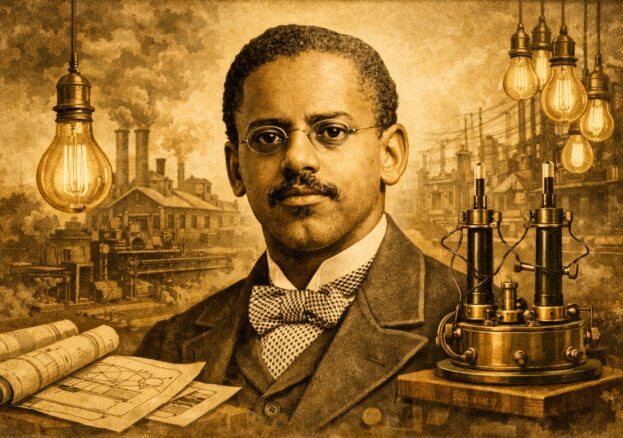

Lewis Howard Latimer was one such figure.

His work helped transform the electric light bulb from a fragile experiment into a practical and enduring tool of modern life. His drafting skills secured patents that altered the course of communications history. His technical expertise helped electrify cities in the United States and abroad. And yet, despite his extraordinary contributions, Latimer’s name is too often relegated to the margins of the story.

To restore him to his rightful place is not an act of correction alone — it is an act of historical clarity.

A Childhood Shaped by the Struggle for Freedom

Lewis Latimer was born in 1848 in Chelsea, Massachusetts, to George and Rebecca Latimer, formerly enslaved people who had escaped from Virginia. Their journey to freedom was perilous, and their story became nationally known when George Latimer was captured in Boston under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Abolitionists rallied in protest. Public meetings were held. Funds were raised. Eventually, money was collected to purchase George Latimer’s freedom, preventing his forced return to enslavement. The case became a powerful example of resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act and fuelled anti-slavery activism in the North.

For young Lewis, freedom was not an abstract ideal. It was something his parents had fought for, and something that could never be taken for granted.

Opportunities for Black Americans in mid-nineteenth century New England were still sharply limited. Education was uneven, employment prospects narrow. Yet within this environment, Latimer displayed determination and intellectual curiosity.

At fifteen, he enlisted in the United States Navy during the Civil War, serving aboard the USS Massasoit. After the war, he returned to Boston seeking work — and found it at a patent law firm, Crosby & Gould.

He was hired not as an engineer, but as an office boy.

Self-Taught Mastery

The patent office proved to be Latimer’s true classroom.

Patent law firms relied on precise technical drawings to accompany applications. These illustrations required accuracy, mechanical understanding and artistic skill. Latimer observed the draftsmen closely. In the evenings, he practised. He studied geometry and mechanical principles independently. Over time, his talent became undeniable.

Within a few years, he had risen to the position of head draftsman — an extraordinary achievement for a Black man in the 1870s.

His breakthrough moment came in 1876, when Alexander Graham Bell rushed to finalise drawings for his telephone patent application. Latimer was entrusted with preparing the detailed diagrams. The clarity and technical precision of those drawings were instrumental in securing Bell’s claim, just ahead of competing inventors.

It was a pivotal moment in communications history. And Latimer was central to it.

Yet drafting patents for others was only the beginning of his career in innovation.

Improving the Light Bulb

The late nineteenth century was defined by a race to harness electricity. Thomas Edison’s work on the incandescent light bulb marked a turning point — but early versions of the bulb had significant limitations. Chief among them was the fragility and short lifespan of the carbon filament inside the glass.

A bulb that burned out quickly was not commercially viable.

Latimer recognised this challenge and developed a method for producing more durable carbon filaments. In 1881, he patented a process that improved both the efficiency and longevity of incandescent bulbs. His innovation reduced manufacturing costs and made electric lighting more practical for widespread adoption.

This was not a minor refinement. It was a critical advancement in making electric lighting commercially sustainable.

Latimer’s expertise soon brought him into direct collaboration with Edison’s enterprise. He joined the Edison Electric Light Company and later became a founding member of the Edison Pioneers — the only Black member of that elite group of early electrical engineers.

His responsibilities extended beyond laboratory work. Latimer supervised the installation of electric lighting systems in major cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Montreal and London. He travelled internationally, representing cutting-edge American technology abroad.

In an era defined by rigid racial hierarchies, Latimer operated at the forefront of industrial transformation.

A Broader Intellectual Life

Latimer’s achievements were not confined to engineering.

In 1890, he published Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System, one of the earliest comprehensive guides to electric lighting technology. The book demonstrated not only his technical mastery but his ability to translate complex systems into accessible explanations. He understood that innovation required both invention and education.

Beyond science, Latimer was also a poet and musician. He wrote verse, played instruments and engaged in cultural life within his community. His intellectual breadth challenges modern assumptions that technical minds operate separately from artistic sensibilities. For Latimer, creativity was holistic.

He was also active in civic and community affairs, contributing to discussions about racial equality and professional advancement for Black Americans. His career stood as quiet evidence of Black excellence in fields that were often systematically closed to people of colour.

Recognition and Erasure

Despite his accomplishments, Latimer did not receive the level of recognition afforded to some of his contemporaries. The narrative of the light bulb became strongly associated with Edison alone. The collaborative networks of engineers, draftsmen and innovators who made electrification possible were often omitted from popular memory.

This pattern was not unique to Latimer. The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries contain numerous examples of Black inventors whose contributions were minimised or obscured by structural racism and selective historical storytelling.

Yet Latimer’s work is woven into the infrastructure of modern life.

Electric lighting extended productive hours, reshaped urban design, improved public safety and transformed domestic routines. Factories operated more efficiently. Streets became safer after dark. Homes were no longer reliant on candles or gas lamps. The rhythms of daily life shifted.

Latimer helped make that transformation durable and scalable.

To acknowledge this is not to diminish Edison or others, but to recognise that innovation is rarely solitary. It is collaborative, layered and dependent on skilled individuals across disciplines.

A Life of Enduring Significance

Lewis Latimer died in 1928 in Queens, New York. By that time, electric light was no longer a novelty; it was an expectation. Cities glowed at night. Industry depended upon electrification. The world had changed.

Today, his legacy stands as both inspiration and instruction.

Inspiration, because his life demonstrates intellectual resilience in the face of systemic barriers. As the son of formerly enslaved parents, operating in a racially stratified society, Latimer achieved professional distinction through discipline and self-education.

Instruction, because his story reminds us that historical narratives require continual reassessment. Who is remembered? Who is footnoted? Who is omitted?

As conversations about representation in science, technology, engineering and mathematics continue in the twenty-first century, Latimer’s life feels strikingly contemporary. He embodied technical excellence long before diversity initiatives or inclusion strategies existed. His presence in elite engineering circles was not symbolic; it was substantive.

Every illuminated office tower, every hospital ward lit through the night, every railway platform glowing under electric light owes something to the evolution of incandescent technology. That evolution bears Latimer’s imprint.

Restoring the Record

To write Lewis Latimer back into the centre of the story is not revisionism. It is restoration.

The history of invention is richer, more accurate and more instructive when it reflects the full range of contributors. Latimer’s career bridges abolitionist history, Civil War service, patent law, industrial electrification and early globalisation. Few individuals occupy so many pivotal chapters of nineteenth-century transformation.

He helped secure the patent for the telephone.

He improved the durability of the light bulb.

He authored one of the first practical guides to electric lighting systems.

He installed electrical infrastructure in major cities across continents.

And he did so as the son of people who had once been legally defined as property.

That arc — from enslavement to electrification — is one of the most powerful narratives in American industrial history.

When we speak of the modern world, we often refer to it as an age of illumination. Lewis Latimer helped make that phrase literal.

His legacy deserves to stand not in shadow, but in light.