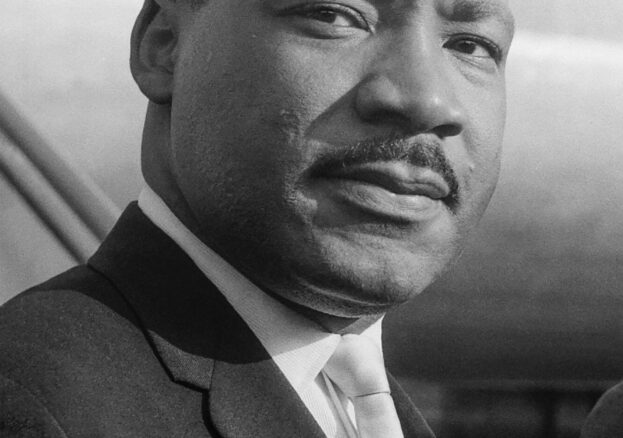

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was not only the most recognisable leader of the American Civil Rights Movement, but also one of the twentieth century’s greatest moral voices. His life tells the story of how conviction, faith, and courage can transform the course of a nation. Though his journey ended with his assassination at just thirty-nine years old, the ideas he preached—justice, non-violence, and love as a force for change—remain alive in struggles for equality across the world.

He was born Michael King Jr. on 15 January 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia, into a world shaped by segregation. His father, Martin Luther King Sr., was a powerful Baptist preacher, and his mother, Alberta, a teacher who passed on her love of music and learning. It was a devout, disciplined household, but also one that instilled in the young King a strong sense of dignity. He grew up in a community where children attended separate schools, where cinemas and buses divided people by race, and where lynchings and intimidation were facts of life. At the age of six, one of his white playmates was told by his parents that he could no longer play with him. It was a painful introduction to the reality of racism, and one King never forgot.

From an early age, his parents encouraged him to believe in himself and in the value of education. He excelled at school and skipped two grades, entering Morehouse College at just fifteen. There, under the influence of the college president, Benjamin Mays, a great preacher and advocate for social justice, King’s calling to ministry deepened. After Morehouse he studied at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where he was elected student body president, and then earned his doctorate in systematic theology at Boston University in 1955. It was during these years that he encountered the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi’s campaigns of non-violent resistance against British colonial rule in India struck King like a revelation. For him, the teachings of Christ provided the spiritual basis of love and justice, but Gandhi had shown how those principles could become the method for mass political action. King would later say: “Christ showed us the spirit, and Gandhi showed us the method.”

In 1954, King accepted his first pastorate at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Just a year later, history called him to leadership. In December 1955, Rosa Parks, a seamstress and activist, refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white passenger. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott. At just twenty-six, King was chosen to lead the newly formed Montgomery Improvement Association. For 381 days, African Americans in Montgomery refused to ride the buses. They walked to work, shared cars, endured harassment and violence, and suffered bombings and arrests. King’s home was bombed, but he refused to back down. His speeches during this period revealed his extraordinary gift: blending the cadence of the pulpit with the urgency of politics, he lifted people’s spirits while giving them practical courage. When the Supreme Court finally ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional, the boycott ended in victory. In his first book, Stride Toward Freedom, King wrote: “The boycott was not a victory for Negroes alone but for all America. It was a moral victory, a vindication of the idea that justice is indivisible.”

From that moment forward, King became the symbol of a rising movement. Over the next decade, he travelled constantly, organising demonstrations, speaking to vast crowds, and enduring arrests and threats. Again and again he called on America to confront its hypocrisy, to live up to its founding ideals. His philosophy was clear: non-violence was not passive but active resistance. “Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon,” he explained. “It is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.”

One of the defining moments came in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. The city was notorious for its segregationist policies and brutal police force. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference launched a campaign of boycotts and sit-ins. The police, led by Commissioner Bull Connor, responded with fire hoses and dogs, and images of children being attacked shocked the world. King himself was arrested and from his cell composed the Letter from Birmingham Jail. In it, he answered white clergy who had criticised him as an outsider and an agitator. His words remain some of the most powerful ever written on justice: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

That same year, King helped lead the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. On 28 August 1963, more than 250,000 people gathered before the Lincoln Memorial. King’s prepared speech shifted when gospel singer Mahalia Jackson cried out from behind him: “Tell them about the dream, Martin!” Departing from his notes, he delivered the immortal refrain: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.” His words rang with hope but also with urgency. It was not simply a dream of racial harmony, but a demand that America face its debts of justice.

The dream began to find legal expression. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public places. The following year, after the brutal repression of marchers in Selma, Alabama, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, ensuring the right to vote could no longer be denied. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, becoming the youngest recipient in history at the time. His acceptance speech in Oslo reminded the world that “nonviolence is not sterile passivity, but a powerful moral force which makes for social transformation.”

Yet King never allowed himself to be satisfied with partial victories. In the final years of his life, his message grew more radical. He condemned the Vietnam War, declaring: “We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for victims of our nation and for those it calls enemy. A time comes when silence is betrayal.” He also turned increasingly toward economic justice, launching the Poor People’s Campaign in 1967 to demand jobs, housing, and dignity for all. “The curse of poverty has no justification in our age,” he declared. “The time has come for us to civilise ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty.” His widening focus made him a controversial figure. Many political allies distanced themselves, but King insisted that racism, poverty and militarism were intertwined evils.

King’s influence was not confined to the United States. After receiving the Nobel Prize, he visited London in December 1964, speaking at St Paul’s Cathedral to a crowd of more than 3,000. He reminded them that the struggle for equality was not American alone but a universal human struggle. For Black communities in Britain, his words carried deep resonance, linking their experiences of discrimination to a broader global movement for dignity.

On 3 April 1968, King stood in Memphis, Tennessee, supporting striking sanitation workers who carried signs reading “I Am a Man.” That evening, he delivered what would be his final address, known as the Mountaintop Speech. His voice, weary but resolute, carried a haunting prescience: “I’ve been to the mountaintop. I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.” The next evening, 4 April 1968, he was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. He was only thirty-nine years old.

His death was a devastating blow, but his legacy only grew. Streets, schools and memorials bear his name. His birthday is honoured as a national holiday in the United States. His words echo through movements from anti-apartheid in South Africa to Black Lives Matter today. He remains the embodiment of moral courage, a reminder that justice is never handed down but won through struggle. As he once said: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Yet King insisted it did not bend by itself. It bent only when people, standing together, bent it.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life was short, but his vision was vast. He showed that non-violence is not weakness but strength, that love can be a political force, and that dreams can be blueprints for action. More than half a century after his assassination, his voice remains the conscience of history, calling us still to live as though justice is possible, to act as though equality is within reach, and to believe, as he did, that freedom is the destiny of all.

Further Reading & Sources

- King, Martin Luther Jr. Stride Toward Freedom (1958)

- King, Martin Luther Jr. Why We Can’t Wait (1964)

- King, Martin Luther Jr. Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (1967)

- The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., ed. Clayborne Carson (1998)

- Stanford University King Institute (archives of writings and speeches)

- Eyes on the Prize (PBS Documentary)

- The Guardian: “Martin Luther King Jr. in Britain” (2014, on his St Paul’s Cathedral visit)

- The King Center, Atlanta