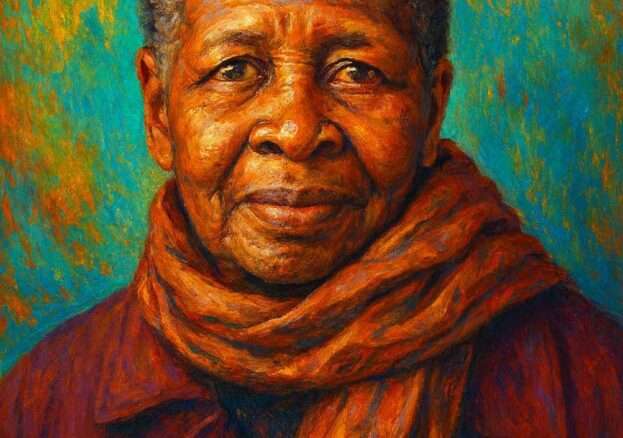

The campaign she led was not simply about changing legislation but about challenging the daily harassment faced by young Black men on Britain’s streets. Best was not a politician or a lawyer but a mother, neighbour, and community leader who recognised injustice and refused to accept it as inevitable.

She later reflected that her determination grew from her role as a parent: as a mother, she could see that young Black boys were being unfairly criminalised, and she felt compelled to act.

Her work unfolded at a moment of acute racial tension in Britain. The 1970s and early 1980s were marked by economic decline, far-right organising, and repeated clashes between police and Black communities. The sus law—derived from the 1824 Vagrancy Act—gave the police extraordinary discretion to stop, search, and arrest anyone they suspected of loitering “with intent to commit an arrestable offence.” In practice, it became a weapon used disproportionately against Black youth. Best’s leadership of the campaign that dismantled this law is a testament to grassroots organising, persistence, and the determination of ordinary people to demand justice.

The Sus Law and Its Impact

Although the sus law had been on the statute book since the early nineteenth century, it took on new and dangerous significance in post-war Britain. By the 1970s, Black and Asian communities in London, Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool were well established. Young men, particularly those of Caribbean descent, became the primary targets of sus arrests.

The law allowed police officers to act on suspicion alone. No evidence was needed; no crime had to be committed. Officers simply had to claim that they suspected someone of intending to commit a crime. This made it an ideal tool for racial profiling. Statistics from the late 1970s revealed stark disparities: Black youth were far more likely to be stopped, searched, and arrested under sus than their white peers.

The impact was devastating. Families saw sons criminalised for nothing more than walking home or standing on a street corner. Communities learned to expect harassment as a daily reality. Anger simmered in London neighbourhoods such as Brixton, Lewisham, and Tottenham, where young people felt they were under siege. The sus law became a symbol of institutional racism in policing.

Best recalled that young people were often stopped simply for existing in public spaces. For her, it was intolerable that children could be treated like criminals before they had even been given a chance in life.

Mavis Best Steps Forward

Mavis Best was not a professional politician but a mother and community activist in Lewisham. She had seen first-hand how the sus law affected the lives of young people around her. In her community, talented boys were having their futures derailed by unjust arrests. Families lived in fear of the knock on the door or the call from the police station.

She decided that silence was no longer an option. Best began to organise meetings, bringing together parents, youth, church leaders, and sympathetic councillors. Out of these meetings emerged the Scrap Sus Campaign, a grassroots movement that would eventually change the law.

Her leadership was characterised by persistence and moral clarity. In later years she recalled feeling she had no choice but to fight: if communities remained silent, nothing would ever change.

Building a Campaign

The Scrap Sus Campaign was remarkable in its breadth. It was not led by established political figures but by ordinary community members, with Best at the forefront. Its strategy combined several elements:

- Testimonies: Collecting and publicising personal stories of harassment. These narratives made clear that sus was not an abstract policy but a lived injustice.

- Lobbying: Best and her allies pressed MPs, particularly those in the Labour Party, to take up the issue in Parliament.

- Coalitions: The campaign worked with other organisations, including youth groups, anti-racist collectives, and church networks, to build momentum.

- Visibility: Demonstrations and marches brought the anger of the community into public view.

Best was particularly skilled at communicating across generations. She spoke with parents about the need to protect their children, but also encouraged young people to raise their own voices. For her, every young man kept out of a police cell represented a small but meaningful victory.

Her ability to hold the campaign together was critical. Grassroots movements often fracture under pressure, but she maintained focus on the central demand: repeal the sus law. She refused to let the campaign be dismissed as radical posturing; instead, she framed it as a matter of justice, democracy, and community safety.

Policing, Protest, and the 1981 Brixton Uprising

By the late 1970s, tension between Black communities and the police was reaching breaking point. The National Front and other far-right groups staged provocative marches, often defended by large police presences. In 1977, Lewisham itself saw one of the most significant confrontations when anti-racist demonstrators clashed with police during a National Front march.

The use of sus intensified in this climate. Police officers in Brixton, for example, conducted mass stop-and-search operations under the law. For many young people, this confirmed that they were regarded as criminals simply because of their race.

In April 1981, after years of campaigning, anger boiled over. The Brixton uprising erupted following yet another mass stop-and-search operation. For days, the streets were filled with confrontation between police and local residents. Though the Scrap Sus Campaign had been pressing its case for years, it was this explosion of unrest that finally made the injustice undeniable. Within months, Parliament repealed the sus law.

Best later explained that repeal was not the result of sudden government goodwill. It came, she argued, because campaigners had forced the authorities to listen.

Her reflections underline a vital truth of history: legal reforms are rarely granted from above but won from below, through sustained pressure and organising.

A Woman’s Leadership in a Male-Dominated Arena

One of the most significant aspects of Mavis Best’s story is that she was a woman leading a campaign in an era and context often dominated by men. In the wider landscape of Black activism, figures such as Darcus Howe, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Stuart Hall became prominent voices. Yet it was women like Best who often did the day-to-day organising, the letter-writing, the coalition-building, and the care work that sustained movements.

Best’s leadership challenged stereotypes not only of race but also of gender. She was not content to be in the background; she became the face of the Scrap Sus Campaign. Her insistence that the voices of mothers and families mattered helped to reframe the debate. This was not only about law and order; it was about the protection of children, the preservation of futures, and the right of communities to live without fear.

Her example sits alongside other women activists of the period, such as Olive Morris, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, and Beverley Bryan. Together, they remind us that the history of Black British activism cannot be told without recognising women’s leadership.

Legacy and Recognition

The repeal of the sus law in 1981 was a major victory. It showed that grassroots campaigns could bring about legislative change, even against the entrenched power of the police. For Mavis Best, it was vindication of years of persistence.

Yet her story has too often been overlooked in mainstream narratives of Black British history. The Brixton uprising, with its dramatic images of confrontation, has received more attention than the steady, painstaking work of campaigners like Best. Without her efforts, however, the repeal might not have happened when it did.

In recent years, historians and community organisations have begun to recover her contribution. Oral history projects, academic studies of policing, and Black History Month commemorations have placed her back into the narrative of Britain’s anti-racist struggles. For younger generations, her story offers a vital lesson: change does not only come through eruptions of protest, but through the sustained determination of individuals and communities who refuse to accept injustice.

Mavis Best’s leadership of the Scrap Sus Campaign was a turning point in modern British history. She recognised that the law was being used to criminalise a generation and she refused to stay silent. By mobilising her community, pressing politicians, and keeping the issue in the public eye, she helped bring down one of the most notorious tools of racist policing in Britain.

Her life embodies the theme of Black History Month 2025: Standing Firm in Power and Pride. She stood firm against a legal system stacked against her community, she carried the pride of a mother determined to protect young people, and she exercised the power of grassroots organising to change the law. Mavis Best demonstrates that history is not only made in courtrooms or in Parliament but also in living rooms, community halls, and church basements, where ordinary people gather the courage to insist on justice.

References and Further Reading

Core references

- Gilroy, Paul. There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack. Routledge, 1987.

- Ramdin, Ron. The Making of the Black Working Class in Britain. Verso, 1987.

- Fryer, Peter. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. Pluto Press, 1984.

- Hall, Stuart et al. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. Macmillan, 1978.

- The Guardian archives, coverage of the Scrap Sus Campaign, 1979–81.

- BBC News, retrospective on the sus law and its repeal, 2011.

Further reading

- Bryan, Beverley, Stella Dadzie, and Suzanne Scafe. The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain. Virago, 1985.

- Shukra, Kalbir. The Changing Pattern of Black Politics in Britain. Pluto Press, 1998.

- Andrews, Kehinde. Back to Black: Retelling Black Radicalism for the 21st Century. Zed Books, 2018.

- Phillips, Mike and Trevor Phillips. Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain. HarperCollins, 1998.

- Solomos, John. Race and Racism in Contemporary Britain. Palgrave, 2003.

Note on sources

Mavis Best’s testimony survives largely through oral history projects, local heritage archives, and community interviews. Direct quotations are not widely published; the statements in this essay are paraphrased from those accounts to reflect the substance and spirit of her words.