In October 1945, in the grey northern city of Manchester, history gathered in a hall. Students, workers, writers and activists came together in Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall for the Fifth Pan-African Congress. They were Africans and Caribbeans, Britons and Black Americans, voices drawn from across the scattered world of empire. They came to speak of freedom, to denounce colonialism, to insist that Africa would not wait another generation. Among them was a young Ghanaian student named Kwame Nkrumah. He was not yet a president, not yet the man whose words would send shockwaves across a continent. But in Manchester he found his stage, his cause, and his destiny.

Eighty years later, we remember that moment not as a footnote but as a beginning. The Pan-African Congress of 1945 declared that independence must come, not in decades but now. It gave urgency to a movement that had too often been dismissed as a dream. Nkrumah was one of the organisers, working with George Padmore and Amy Ashwood Garvey, listening to the oratory of W.E.B. Du Bois, debating with Jomo Kenyatta, absorbing the conviction that empire was no longer unshakable. The congress was not only about speeches. It was about resolve. Nkrumah later wrote that Manchester “fired me with a new sense of mission.” That fire would carry him back across the seas, to the Gold Coast, and to the struggle that made him Africa’s first great liberator.

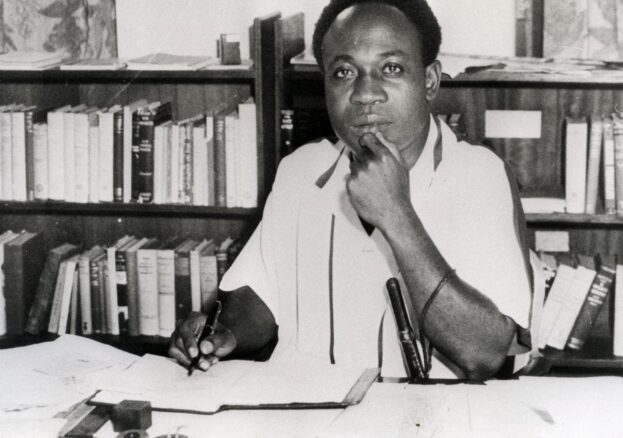

Kwame Nkrumah was born on 21 September 1909 in Nkroful, a small village in the British colony of the Gold Coast. The son of a goldsmith, he grew up in a Catholic household and trained as a teacher. But his mind was restless, reaching beyond the narrow paths laid out by colonial education. He read voraciously, absorbing not only history and philosophy but the rising tide of Black political thought. In 1935 he sailed for the United States, enrolling at Lincoln University, the first historically Black university. There he studied economics, sociology and theology, later earning a Master’s degree in political science at the University of Pennsylvania.

America gave him both hardship and inspiration. He worked odd jobs to survive, but he also found himself immersed in Harlem’s political ferment. He read Marcus Garvey, debated socialism, listened to the cadences of African American preachers, and came to believe that liberation was both a political and a spiritual task. Colonialism, he saw, did not only chain nations. It also colonised the mind. To free Africa, Africans would have to believe in themselves again.

In 1945 he moved to London. Britain was still war-scarred, rationing its food and rebuilding its cities. But in the cafés and meeting halls of London, colonial students gathered, impatient for change. It was here that Nkrumah met George Padmore, the Trinidadian radical who became his mentor, and Amy Ashwood Garvey, who channelled the energy of Caribbean activism into global debate. Together, with W.E.B. Du Bois presiding as elder statesman, they organised the Manchester congress. The hall was shabby, the world still weary from war, but the words spoken there resounded like a trumpet: “We are determined to be free. We want education. We want the right to govern ourselves. We shall not rest until we have won our independence.”

For Nkrumah, Manchester was decisive. It confirmed what he already suspected — that gradual reform, the cautious path urged by colonial officials, was no longer acceptable. Africa’s time had come.

In 1947 he returned to the Gold Coast as General Secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention, a nationalist party led by cautious professionals. But his impatience soon put him at odds with them. In 1949 he broke away to form the Convention People’s Party (CPP), with its uncompromising slogan: “Self-government now!” His genius was organisation. He rallied not only elites but workers, women, students, and market traders. He toured the country tirelessly, speaking in towns and villages, calling people to action. His charisma was undeniable. He had the ability to make ordinary Ghanaians feel part of something larger than themselves — a people rising.

The colonial government responded with repression. In 1950, Nkrumah launched a campaign of “Positive Action” — strikes, boycotts, civil disobedience. He was arrested and imprisoned. Yet his popularity only grew. In 1951, while still in prison, his party won a landslide election. The British were forced to release him. Within months he was Prime Minister. And in 1957, standing before a sea of people in Accra’s Independence Square, he proclaimed Ghana’s freedom: “At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country, is free forever.”

The symbolism was immense. Ghana was the first Black African nation to gain independence from colonial rule. The ripple spread across Africa. In Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, and beyond, Nkrumah’s triumph showed what was possible. But for Nkrumah himself, Ghana was not the endpoint. It was only the beginning. “Our independence,” he declared, “is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of Africa.”

He became the continent’s foremost champion of Pan-Africanism. He called for a Union of African States, with one currency, one army, one destiny. He believed only unity could protect Africa from the new forms of domination he called “neo-colonialism.” In 1963, at the founding of the Organisation of African Unity in Addis Ababa, he warned: “We must unite now or perish.” Many admired his vision, but few shared his urgency. African leaders, newly independent themselves, were reluctant to surrender sovereignty to a continental union. Still, Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa continues to inspire debate today.

At home, his ambitions were grand. He launched plans for industrialisation, modern infrastructure, mass education, and healthcare. He built the Akosombo Dam to electrify the country, created Lake Volta, and founded new universities. He sent students abroad to study science and technology. He wanted Ghana to leap forward, to be the beacon of African modernity. For a time, optimism soared.

But reality was harder. The economy, reliant on cocoa, struggled with world price fluctuations. The costs of Nkrumah’s projects mounted. His government became increasingly authoritarian. He introduced the Preventive Detention Act, allowing imprisonment without trial. Opposition parties were harassed, newspapers closed. His image appeared everywhere, his titles grew more extravagant. To some he was “Osagyefo” — the Redeemer. To others he seemed a leader slipping into personality cult.

Even as tensions grew, Nkrumah remained an international figure of renown. Perhaps the most symbolic moment came in November 1961, when Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip made a state visit to Ghana. There were grave security fears after bomb attacks in Accra earlier that year, and many in Britain urged the Queen not to go. But she insisted, determined to show solidarity. At a glittering state banquet, under the gaze of the world’s press, she stepped onto the dance floor with President Nkrumah. Together they danced a foxtrot. The image was electrifying: a young white monarch of empire dancing with the Black president of a newly independent African nation. It was more than courtesy. It was recognition. In an age when apartheid still reigned in South Africa, the photograph of Nkrumah and the Queen was a rebuke to racism and a symbol of Ghana’s sovereignty. Harold Macmillan, the British Prime Minister, said later that the Queen’s gesture “did more good than a hundred speeches.”

Nkrumah’s story, though, is not told in symbols alone. It is remembered most vividly in Ghana, where his place in history is both secure and debated. In Accra, the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum and Memorial Park stands as a monument to his role as founding father. His birthday, 21 September, is a national holiday. Schoolchildren learn that in 1957 he led Ghana to independence, the first in Black Africa. For many, he remains the man who gave a people its pride. Yet Ghanaians also remember his authoritarian turn — the detentions without trial, the silenced newspapers, the growing personality cult. Older generations recall the shortages and the debts of the 1960s. For some, the coup that toppled him in 1966 was a moment of relief, for others a tragedy. Today, young Ghanaians admire him as a visionary whose dreams of industrialisation and African unity were ahead of their time. His warnings about neo-colonialism are still quoted in debates about economics and politics. Even critics acknowledge he gave Ghanaians and Africans dignity. “Osagyefo” — the Redeemer — remains a title spoken with affection.

The Cold War sharpened his difficulties. Courting both East and West, he accepted aid from Moscow and Beijing, alarming Washington and London. In February 1966, while on a visit to North Vietnam and China, his government was overthrown in a coup. Evidence later revealed CIA involvement. Nkrumah never returned to Ghana. He lived in exile in Guinea, welcomed by President Ahmed Sékou Touré, who made him honorary co-president. In 1972, aged just 62, he died of cancer in Bucharest, Romania.

Even in exile, his reputation endured. When his body was flown home, Ghanaians lined the streets to mourn. He had been deposed, criticised, even feared — yet he was still loved as the man who had given them freedom. Today he is honoured as the founding father of Ghana, his mausoleum a place of pilgrimage, his name invoked whenever African unity is discussed.

Kwame Nkrumah’s legacy is not simple. He was a liberator and a dreamer, but also a ruler who suppressed dissent. His economic plans were visionary, but his methods harsh. Yet his importance cannot be measured by Ghana alone. His greatest achievement was to place Africa on the world stage as a continent that would no longer be ruled. He gave Africans a new pride, a new vocabulary, a new demand.

Eighty years on from Manchester, we can see the arc of his life. In that northern English city, amid the soot and the post-war austerity, he helped to declare an African future. In Accra, a dozen years later, he proclaimed it real. In the banquet hall of Accra, dancing with the Queen of England, he showed the world that colonial hierarchy was over. And even when his dreams of unity faltered, he kept insisting that Africa’s destiny was in its own hands.

He once said: “Freedom is not something that one people can bestow on another as a gift. They claim it as their own and none can keep it from them.” That sentence could be carved across the walls of Manchester Town Hall, across the streets of Accra, across the continent he dreamed of. It is a reminder that freedom is not granted. It is taken.

Kwame Nkrumah was, and remains, the voice that spoke in Manchester and the dreamer who envisioned an Africa reborn. His time has passed, but his words endure. And as we mark the 80th anniversary of that congress, we do not only remember what was said. We remember that it changed history.

Books

- Kwame Nkrumah, Africa Must Unite (1963)

- Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (1965)

- David Birmingham, Kwame Nkrumah: The Father of African Nationalism (1990)

- Ama Biney, The Political and Social Thought of Kwame Nkrumah (2011)

Online References