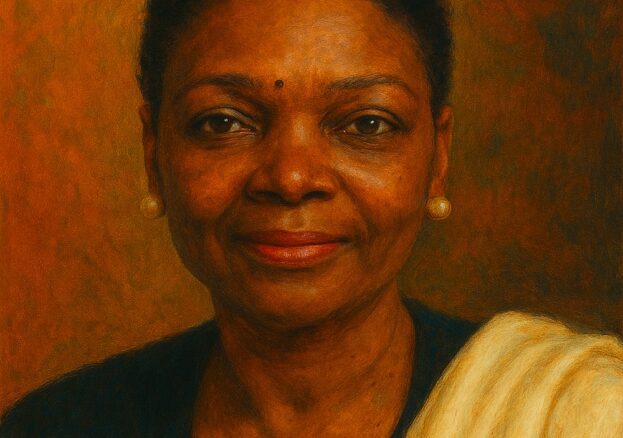

On a spring morning in 2003, Valerie Amos walked into the Cabinet Room of 10 Downing Street. Cameras flashed, journalists scribbled, and the history books took note. She was there as Britain’s new Secretary of State for International Development — the first Black woman ever to sit at the Cabinet table. It was a quiet moment, without fanfare, but it resounded far beyond Whitehall. For generations, Black Britons had lived, worked, and built lives in this country without seeing anyone like themselves at the pinnacle of political power. Amos’s appointment was more than personal achievement. It was a door opening.

That has been the rhythm of her life: a series of firsts, each one prising open a space that had long been closed. First Black woman in the Cabinet. First Black woman to lead the House of Lords. First Black woman to head a British university. First Black person to lead an Oxford college in its 900-year history. These are not footnotes. They are milestones in the story of Britain itself.

That has been the rhythm of her life: a series of firsts, each one prising open a space that had long been closed. First Black woman in the Cabinet. First Black woman to lead the House of Lords. First Black woman to head a British university. First Black person to lead an Oxford college in its 900-year history. These are not footnotes. They are milestones in the story of Britain itself.

Valerie Ann Amos was born on 13 March 1954 in British Guiana, now Guyana. Her family emigrated to Britain when she was a child, part of the wave of Caribbean migration that reshaped the nation in the 1950s and 60s. They arrived with the promise of opportunity, but also into a society that did not always welcome them. Growing up in North London, Amos saw first-hand the barriers faced by immigrant families — racism, housing discrimination, and the quiet exclusions of daily life. But she also saw resilience: communities that organised, supported one another, and believed that education could change everything.

She excelled at school and went on to study Sociology at the University of Warwick, later earning a Master’s degree in Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. Her academic path reflected her interests: how societies work, how cultures intersect, how power operates. These were not abstract concerns. For a young Black woman in Britain in the 1970s, they were lived realities.

Her career began not in the rarefied world of Westminster but in local government and the voluntary sector. She worked in Equal Opportunities and human resources, specialising in issues of race and gender equality. From 1989 to 1994 she served as Deputy Chief Executive of the Equal Opportunities Commission, helping to push for fairer employment practices at a time when “diversity” was still far from a household word. Colleagues recall her as calm, precise, and utterly determined — a woman who would not be deflected once she set her mind to a task.

In 1997, after years of community and policy work, she was made a life peer, taking the title Baroness Amos of Brondesbury. The red benches of the House of Lords were a world away from her childhood in Guyana, but she carried herself with quiet assurance. She became a Government Whip and, in 2001, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State in the Department for International Development. There she worked on aid, trade, and Britain’s responsibility to the world’s poorest communities.

Two years later came her breakthrough moment. When Clare Short resigned from the Cabinet in May 2003, Valerie Amos was appointed as Secretary of State for International Development. She was the first Black woman ever to serve in the British Cabinet. It was a short tenure — just a few months — but its symbolism was immense. Diane Abbott, the first Black woman MP, later said: “Valerie being in Cabinet mattered. It told our communities that the very highest offices were not closed to us.”

Later that year she was appointed Leader of the House of Lords and Lord President of the Council. Once again, she was the first Black woman to hold those roles. The responsibilities were immense: steering government business through the Lords, negotiating with peers, and managing legislation in one of Britain’s oldest institutions. Some doubted whether a Black woman could command such a chamber. Amos proved them wrong. “Her style was firm but never aggressive,” one colleague recalled. “She had authority without needing to shout.”

Her career then turned outward, onto the global stage. In 2010 she was appointed Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator at the United Nations. There she confronted crises that tested the world’s conscience: the earthquake in Haiti, famine in Somalia, the war in Syria. She travelled to disaster zones, met displaced families in refugee camps, negotiated with governments, and coordinated international aid. Her words were often stark: “The world must not turn its back on those in desperate need.” In a field dominated by bureaucracy and politics, she insisted on humanity.

After five years at the UN, she returned to Britain to take up another pioneering post. In 2015 she became Director of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), the first Black woman to lead a UK university. Her tenure was marked by efforts to diversify the curriculum and strengthen the institution’s global reputation. It was not without challenges — SOAS faced financial difficulties and debates about direction — but her appointment alone was historic. For Black students, seeing a Black woman at the head of a university was a moment of recognition.

In 2020 she became Master of University College, Oxford — the first Black person ever to head an Oxford college. That single fact resounded. Oxford, with its centuries of tradition and its image as the preserve of the privileged, had finally placed a Black woman at the helm of one of its ancient colleges. For students from minority backgrounds, her appointment was a beacon. “Representation matters,” she said on her arrival. “We must make sure our institutions reflect the societies we live in.”

The honours followed. In 2016 she was made a Companion of Honour for her services to the United Nations and humanitarian causes. In 2022 she carried one of the coronation regalia at the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, a visible emblem of how much had changed in her lifetime. For the girl from Guyana who had once walked into a British classroom as an outsider, it was a moment of profound symbolism.

Yet Amos’s career has never been only about titles or honours. It has always been about service. From community activism in North London to the corridors of the UN, from voluntary sector campaigns to Oxford’s dreaming spires, her thread has been the same: opening doors for others. She has spoken often about the need to challenge institutions to be better. “If we want real change,” she has said, “we must be willing to challenge, to push, and to keep pushing until barriers come down.”

Her legacy is not without complexity. Some critics felt she was too cautious in government, too willing to work within the system rather than against it. At SOAS, debates raged about finances and the university’s future direction. Yet even in critique, her presence marked progress. For centuries, women like her were absent from the rooms where decisions were made. Her very existence in those rooms has altered the expectations of what is possible.

Baroness Valerie Amos’s life is also part of a wider story: the story of Black Britain. The children of Windrush who grew up facing hostility but refused to be diminished. The generation of pioneers who claimed seats in Parliament, places in universities, and roles in public life once denied them. Amos stands alongside Diane Abbott, Bernie Grant, Paul Boateng, and others as part of that first wave who made Britain confront its own diversity. Her story reminds us that progress is not automatic. It is made, often painstakingly, by those who break ground.

Today, as debates about race, equality, and belonging continue, her example matters more than ever. She embodies what it means to be the first: not just to arrive, but to change the space so others can follow. Her life is proof that representation is not a token, but a transformation.

In the end, Baroness Amos is not only a figure of firsts. She is a figure of continuity — someone who has carried the principles of justice, equality and service across every role she has held. She has stood in rooms where no Black woman had stood before, and she has left those rooms altered. That is her legacy. And it is one that Britain, in all its diversity, must cherish.