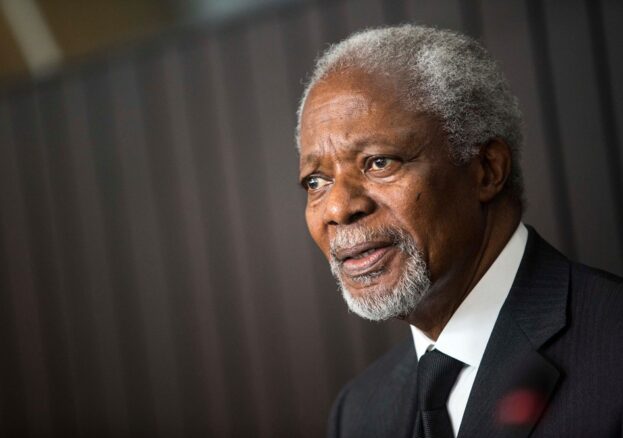

He was a quiet man in a noisy world. Kofi Annan, the Ghanaian diplomat who rose to become Secretary-General of the United Nations, carried himself with calm grace in the midst of global storms. Where others shouted, he listened. Where others sought to dominate, he sought to persuade. Where others saw politics, he insisted on humanity. His legacy is not only in the resolutions passed, the initiatives launched, the medals awarded, but in the way he reminded the world that peace is a duty as well as a dream.

Kofi Atta Annan was born on 8 April 1938 in Kumasi, in the heart of Ghana, then the British colony of the Gold Coast. His father was a provincial governor in the Ashanti region, his family respected, his household modest but proud. He grew up in a world that was African yet marked by the structures of empire, a world that demanded patience and persistence to rise. At the Methodist-run Mfantsipim School he learned discipline, fairness and service. It was there that he began to believe, as he later put it, that “suffering anywhere concerns people everywhere.” He studied economics in Ghana before his path took him abroad: to Macalester College in Minnesota, then to the Graduate Institute in Geneva, and later to the Sloan School of Management at MIT. He was shaped by Africa but trained by the world. He belonged everywhere and yet never forgot where he came from.

In 1962 he joined the United Nations, working for the World Health Organization. It was not glamour, but it was service. He moved through postings in Geneva, Cairo, New York, absorbing the rhythms of an organisation that carried noble ambitions but was often entangled in bureaucracy and the competing demands of great powers. Annan had a rare gift: he could calm a room. His quietness was not weakness but strength, a patience that allowed others to be heard before he spoke. “Quiet diplomacy,” he would later say, “is far more effective than shouting from the rooftops.”

By the early 1990s he had become Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping, responsible for UN forces in some of the most dangerous regions on earth. It was a role that tested him and left scars. In Rwanda, in 1994, while the international community debated and delayed, hundreds of thousands of men, women and children were slaughtered in a genocide that unfolded in plain sight. The UN did not act in time, and Annan never forgot the failure. “The international community failed Rwanda,” he admitted, “and that must leave us always with a sense of bitter regret.” A year later, in Srebrenica, Bosnian Muslims were massacred despite the presence of UN peacekeepers. These tragedies seared themselves into his conscience. They shaped his determination that the United Nations must not simply monitor atrocities but be prepared to prevent them. From those failures emerged one of his most important contributions to global governance: the principle of the Responsibility to Protect, the idea that sovereignty could not be a licence for governments to kill their own people.

In 1997, Kofi Annan was appointed Secretary-General of the United Nations, the first sub-Saharan African to hold the post. His election was historic. His presence was striking. Slim, silver-haired, dignified, he embodied a style of leadership that was the opposite of bluster. He exuded calm authority, the kind that could steady negotiations simply by walking into a room. He was not a showman, not a populist, but a statesman of quiet determination.

He served two terms, from 1997 to 2006, years of turmoil and upheaval. He was Secretary-General during the Balkan wars, during the attacks of 11 September 2001, during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. He spoke for peace when many clamoured for war. He condemned the Iraq War as “illegal” under the UN Charter, a rare moment when a Secretary-General publicly defied the most powerful country in the world. It was a moment that endeared him to the Global South and to those who believed that law, not force, should govern international relations.

His achievements were significant. He helped launch the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, directing billions of dollars into saving lives. He oversaw the creation of the Millennium Development Goals, a framework to reduce poverty, hunger and disease that guided policy across the world. He championed human rights, good governance and the rule of law, and pushed for reform of the UN itself, seeking to make it more transparent and responsive. For these efforts, he and the United Nations were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001 “for their work for a better organised and more peaceful world.”

But his time was not without controversy. The Oil-for-Food scandal in Iraq tarnished his second term, even though he was personally cleared of wrongdoing. Critics said he was too cautious, too wedded to process, too reluctant to confront powerful states head-on. Yet those who worked with him knew that his strength lay precisely in his patience, his ability to keep the doors of dialogue open when others had slammed them shut. He knew that diplomacy is not about winning, but about surviving the night, keeping the conversation alive, holding the line until peace has a chance to emerge.

Kofi Annan’s ties to Britain were deep and enduring. He was a regular visitor, welcomed at Downing Street, respected in Parliament, honoured in universities. In 2000, he delivered the Dimbleby Lecture for the BBC, outlining a vision of a global ethic in an age of rapid globalisation. His words resonated particularly in Britain, with its diverse communities and its own debates about immigration, identity and the legacy of empire. He received honorary degrees from the University of Birmingham and the University of London. He was admired in Britain not only as a statesman but as a symbol: a Ghanaian, an African, a man from the continent once colonised, now standing at the pinnacle of the world’s diplomacy. For Black Britons, he was living proof that the highest offices of the world were not closed to them.

When he stepped down in 2006, he did not retire to silence. He founded the Kofi Annan Foundation in Geneva, committed to promoting good governance, conflict resolution and youth leadership. He joined The Elders, the group of retired leaders brought together by Nelson Mandela to work for peace and human rights. In 2007–08, when Kenya erupted in violence after contested elections, it was Annan who flew in to mediate, sitting between rivals, coaxing them towards compromise, and helping to avert a civil war. His quietness once again saved lives.

He never lost his optimism. He liked to call himself a “stubborn optimist,” convinced that humanity, for all its failings, could be better. He believed in the potential of the young. “You are never too young to lead,” he said, “and never too old to learn.” His presence at international conferences was always striking: the soft-spoken African, impeccably dressed, insisting on dignity and humanity in a world that too often forgot both.

Kofi Annan died on 18 August 2018, in Bern, Switzerland, at the age of 80. His death was mourned across the globe. In Ghana, his body lay in state for three days as thousands filed past to pay their respects. The flag-draped coffin, the solemn procession, the tears of ordinary citizens spoke of how deeply he had touched his people. At the United Nations headquarters in New York, the flag flew at half-mast. Leaders from every continent paid tribute to his dignity, his calm, his humanity.

Yet perhaps his greatest legacy does not lie in institutions or policies, but in example. He showed that quietness can be strength. He showed that humility can carry more weight than arrogance. He showed that diplomacy, often dismissed as talk, is in fact the patient labour of peace. He embodied the idea that an African, born in colonial Ghana, could stand at the very top of world affairs without losing his roots or his identity.

He left us words worth carrying into the future: “We may have different religions, different languages, different coloured skin, but we all belong to one human race.” In a world riven by division, those words are not sentiment but necessity. He taught that peace is not a dream but a practice, not an aspiration but a duty.

Kofi Annan was, and remains, a symbol of dignity in a turbulent age. He stood for humanity in the face of cruelty, for dialogue in the face of aggression, for humility in the face of power. He was, as Nelson Mandela once said of him, “a true statesman of our times.” And like all true statesmen, his influence will long outlive his years.

Further Reading & References

Books

- Kofi Annan, Interventions: A Life in War and Peace (2012)

- Stanley Meisler, Kofi Annan: A Man of Peace in a World of War (2007)

- Thomas Weiss, What’s Wrong with the United Nations and How to Fix It (2016, revised)

Online Resources