Black History Month is always a moment to pause. A time for all to honour those who came before us, reflect on where we stand, and look ahead to what we are building for the generations to come. This year’s theme—standing firm in power and pride—resonates deeply with me, because I appreciate those words carry different meanings depending on who you are, and the history you inherit.

In the West, power and pride are often associated with dominance, achievement, and individual assertion. In parts of Asia, they may be tied to quiet dignity or harmony with tradition. Through an African lens, they mean something else entirely: reclaiming identity, resisting erasure, and celebrating the strength passed down through generations.

That interpretation has shaped my life.

I was born in Ghana, where identity wasn’t questioned—it simply was. My name, my skin, my heritage were reflected everywhere I turned. There was no undertone of erasure. But when I moved to the UK at five years old to live with my mother—herself born in Britain in the 1960s—things shifted.

Like many children of colour, I learned early that childhood innocence doesn’t last long. The world reminded me—often and unkindly—that I was moving through spaces rarely designed with me in mind. Sometimes the exclusion was unintentional, and at times even understandable. Too often, it was deliberate. I grew up straddling two realities: Ghanaian at home, British outside. Pride felt like something I had to earn. Power, something I had to perform.

Some suggest this unease stems from an “African victim mentality” but such a view dismisses the profound and enduring impact of centuries of racialised colonisation—systematic campaigns that distorted history, devalued identity, disenfranchised societies, and exploited an entire continent in the pursuit of greed. These reverberations do not have a neat end date. They fade, but never fully disappear, and their echo will remain audible for generations to come. What continues to disappoint me is the resistance some still show in acknowledging this truth. Behind that resistance, I see shame—for who wants to be cast as the oppressor in a world that prizes moral superiority? Who wants to accept that the privileges they enjoy are, at least in part, built on tainted foundations?

In ancient times, Africa was cast as a land without history, art, or culture—the very markers the West claimed as the essence of a “civilised” society.

In more recent history, the contributions and sacrifices of African colonial forces in the world wars were erased, buried beneath Eurocentric narratives of dominance. These were not wars fought to preserve African values, but to defend European supremacy. Even in death, soldiers of African descent were denied dignity—refused proper burials, or segregated from their non-African counterparts. Of course, not all individuals subscribed to this—many ordinary people resisted with the sentiment “not in my name”—but power rested in the hands of those who did. There is an old adage: power is never given—it is taken. Our history makes painfully clear how often it was taken from us.

And then there was the classroom. In the West, the curriculum presented Africa almost entirely through the lens of slavery, poverty, and plight. What reason, then, would a young me have to feel power or pride? Especially when the world around me was exporting narratives of Eurocentric excellence across every field—excellence rarely accompanied by acknowledgment of the injustice, exploitation, and moral compromise that underpinned it.

It took years of reflection to understand that neither power nor pride were things I needed to chase. They were already mine. My story as an African may differ from that of many in the diaspora whose families were directly impacted by the slave trade, but one truth unites us: from a global perspective, we share a collective inheritance of power and pride through ancestors who endured, created, resisted, and thrived. My task was not to earn these qualities, but to reconnect with them—to live them fully and unapologetically.

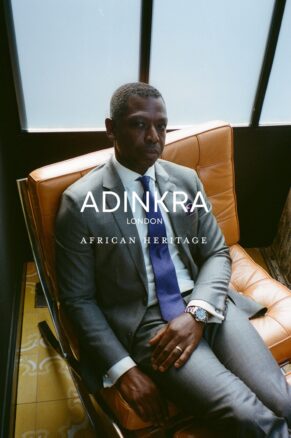

That conviction eventually shaped what I went on to build. I founded ADINKRA not as a conventional fashion business, but as a cultural statement. The name comes from the Ghanaian Adinkra symbols—visual languages of wisdom, resilience, unity, and spirituality. These symbols are more than patterns; they are philosophies. They carried meaning for centuries, even when African voices were dismissed or erased.

That conviction eventually shaped what I went on to build. I founded ADINKRA not as a conventional fashion business, but as a cultural statement. The name comes from the Ghanaian Adinkra symbols—visual languages of wisdom, resilience, unity, and spirituality. These symbols are more than patterns; they are philosophies. They carried meaning for centuries, even when African voices were dismissed or erased.

For me, ADINKRA became a way to carry that heritage forward. To create something that affirms our culture, celebrates its depth, and opens it to wider understanding. It is not fashion for fashion’s sake. It is about ensuring African creativity is recognised as central, not marginal. That our culture is seen not as trend or token, but as both legacy and innovation.

The aim has always been simple: for Africans, ADINKRA is a reminder of the richness we carry. For the diaspora, it is a bridge to traditions that can sometimes feel distant. For non-Africans, it is an invitation to engage with our culture with respect, not appropriation.

In that sense, ADINKRA is my way of standing firm in power and pride. It represents a refusal to let culture be diluted or dismissed. It says: our stories matter. Our symbols matter. Our heritage matters. And we do not need to apologise for centring them.

That feels especially important during Black History Month. Too often, our narratives are reduced to trauma. While we must acknowledge the injustices of our past and present, we must also tell the other side of the story: one of creativity, excellence, and joy. We are not defined solely by survival. We are innovators, builders, dreamers, leaders.

Standing firm in power and pride means embracing that fullness. It means walking into every space knowing that pride is not conditional, and power is not performative. They are ours by right, carried within us, carried forward by us.

As I think about the future, my hope is that children and adults of African ancestry—whether partial or full—will not have to search so hard for reflections of themselves. That they will know, without question, that their heritage is not something to shrink from, but something to stand tall in. That when they stand firm, they will be standing on the shoulders of giants.

And for those without African ancestry, this is not an invitation to carry guilt, but to widen the aperture. To recognise the forces that shape the power and pride they may have inherited at birth, and to understand that true strength is not diminished when it makes space for others to stand tall too.