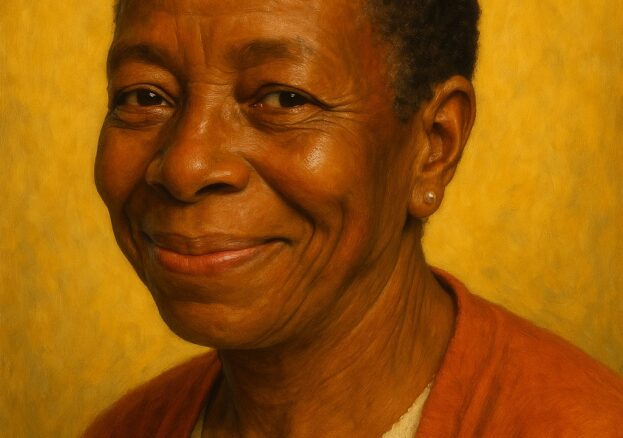

In the history of Black resistance in Britain, few figures capture the intersection of intellect, discipline, and political conviction as powerfully as Altheia Jones-LeCointe. Born in Trinidad in 1945, trained as a scientist, and emerging in Britain as the leader of the British Black Panther Movement (BBPM) in the late 1960s and early 1970s, she was one of the most formidable voices of her generation.

While male figures such as Darcus Howe and Obi Egbuna have often dominated accounts of Black radical politics, Jones-LeCointe’s leadership made the British Panthers one of the most disciplined and politically coherent organisations of its time. She demanded rigour: political education was as important as street protest, and self-discipline was seen as essential to confronting the combined forces of racism and state repression.

Her role in the Mangrove Nine trial of 1970 brought her into the public eye, where she represented herself with eloquence and courage in court, exposing the racism of the police. But her legacy runs deeper: she created an organisational culture that empowered young Black Britons, especially women, to see themselves as agents of change. She was a scientist and activist in equal measure, a woman who refused to accept the boundaries of either race or gender in a society structured to exclude her.

From Trinidad to London: Formation of a Revolutionary

Altheia Jones-LeCointe was born into a middle-class family in Port of Spain, Trinidad. She excelled academically, winning a scholarship to study in Britain. In the mid-1960s, she moved to London to pursue her doctoral studies in haematology. Like many Caribbean students of her generation, she arrived with a mixture of hope and determination. Britain was the former colonial metropole, and London’s universities offered both opportunity and alienation.

As a young Caribbean woman in science, she confronted a double burden. She entered a field where women were underrepresented, and as a Black immigrant she faced the everyday racism of Britain in the 1960s. Landlords displayed “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” signs; the police frequently harassed young Black men; and the press depicted migrants as a problem to be managed. For Jones-LeCointe, the laboratory and the lecture theatre could not be separated from these realities. She came to see her scientific training as a form of discipline that could also be applied to political life: the careful study of structures, the pursuit of truth, and the insistence on method.

Leadership of the British Black Panther Movement

The British Black Panther Movement was founded in 1968, inspired by the radical currents of the global Black Power movement. While smaller and less heavily armed than its American counterpart, the BBPM was rooted in the experiences of Britain’s Caribbean, African, and South Asian communities.

When Jones-LeCointe emerged as its leader, she brought a distinctive style. She emphasised political education: members were expected to attend study groups, read political theory, and learn about colonialism, capitalism, and racism. She insisted on self-discipline: the Panthers were not to be a loose group of angry youth but a disciplined cadre, accountable to the community. And crucially, she made gender equality a principle: unlike many male-dominated organisations of the era, Jones-LeCointe placed women in leadership roles and insisted that sexism be challenged within the movement.

Under her direction, the Panthers campaigned against police brutality, poor housing, and discrimination in education. They set up community “Saturday schools” to teach Black history and organised food and clothing drives for families in need. The organisation was both a political and a social safety net, filling the gaps left by a hostile state.

The Mangrove Nine Trial: Defiance in the Courts

The most famous episode in Jones-LeCointe’s political life came in 1970, when she and eight other activists were arrested following a protest against police harassment of the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill, a hub of the Black community. The protest had been peaceful, but the police charged the nine with incitement to riot and other serious offences.

The trial of the Mangrove Nine became a landmark in British legal and political history. Jones-LeCointe, along with Darcus Howe, chose to represent herself in court. Her defence was uncompromising: she argued that the case itself was political, that the police were acting with racial prejudice, and that the defendants were being punished not for violence but for daring to resist.

The trial lasted 55 days, attracting national attention. In the end, all nine were acquitted of the most serious charges, and the judge—remarkably—acknowledged evidence of “racial hatred” within the Metropolitan Police. This was the first time an English court had made such an admission. Jones-LeCointe’s eloquence and strategic clarity during the trial cemented her reputation as both a lawyerly mind and a fearless activist.

Women in the Movement: Reframing Black Radicalism

One of Jones-LeCointe’s most lasting contributions was her insistence on the role of women in Black radical politics. Too often, histories of Black Power focus on charismatic male leaders, marginalising the women who organised, educated, and sustained the movements. Jones-LeCointe disrupted this pattern.

Under her leadership, women played central roles in the Panthers. They led study sessions, edited newsletters, and ran community programmes. They also challenged sexism within the movement itself. Jones-LeCointe instituted rules against the exploitation of women members, insisting that male members take accountability for their behaviour. This was not without tension—some men resisted what they saw as constraints—but it gave the BBPM a distinctive character compared to many of its contemporaries.

Her approach resonates with later scholarship on Black feminism, which insists that race, class, and gender cannot be separated. Long before these terms became common in British academic circles, Jones-LeCointe was practicing a politics that took them seriously.

Surveillance and State Repression

Like many radical organisations of the time, the British Panthers were subject to heavy surveillance. Special Branch and MI5 monitored their meetings, intercepted communications, and infiltrated members. The state viewed them as a threat, not because they had military capacity but because they were reshaping the political consciousness of young Black Britons.

Jones-LeCointe herself was frequently targeted. The press portrayed her as an extremist, and her scientific career was not immune from the suspicion that surrounded her politics. Yet she continued her dual path: advancing her research in haematology while sustaining the Panthers’ community and political work. This ability to balance two demanding worlds testified to her intellectual stamina and organisational skill.

Later Life and Continuing Influence

In the later 1970s, as the Panthers declined and splintered, Jones-LeCointe stepped back from public leadership. She returned to her scientific career, eventually becoming a respected haematologist and researcher in London hospitals. She rarely gave public interviews about her time as a Panther, preferring to let the work speak for itself.

In recent years, however, her role has been rediscovered and celebrated. Documentaries, academic studies, and public commemorations have highlighted her leadership and the significance of the Mangrove Nine trial. She has become an icon not just of Black Power but of Black women’s leadership in Britain—a reminder that the history of struggle is incomplete if it erases those who organised behind the headlines.

Legacy

Altheia Jones-LeCointe’s legacy is profound. As a scientist, she exemplified excellence in a field that had few women, let alone women of colour. As a Panther, she created a disciplined, politically literate movement that gave young Black Britons the tools to resist. As a defendant in the Mangrove Nine trial, she turned the courtroom into a platform for truth-telling about racism in the police.

For Black History Month 2025, celebrated under the theme Standing Firm in Power and Pride, her story embodies both dimensions. She stood firm against a state apparatus determined to silence her, and she carried pride in her Caribbean heritage, her scientific training, and her political commitments. Her life shows that resistance is not only a matter of protest on the streets but also of building institutions, educating communities, and refusing to let history forget the women who led.

References and Further Reading

Core references

- Olusoga, David. Black and British: A Forgotten History. Pan Macmillan, 2016.

- Howe, Darcus. From Bobby to Babylon: Blacks and the British Police. Race Today, 1988.

- Bunce, Robin and Paul Field. Darcus Howe: A Political Biography. Bloomsbury, 2014.

- Andrews, Kehinde. Back to Black: Retelling Black Radicalism for the 21st Century. Zed Books, 2018.

- BBC. Mangrove Nine Trial, archival coverage, 1970.

- Egbuna, Obi. The Wind of Change: A Call to Action for British Blacks. 1969.

Further reading

- Andrews, Kehinde. Resisting Racism: Race, Inequality, and the Black Panthers in Britain. Pluto Press, 2013.

- Bryan, Beverley, Stella Dadzie, and Suzanne Scafe. The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain. Virago, 1985.

- Matera, Marc. Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the 20th Century. University of California Press, 2015.

- Farrar, Max. The Mangrove Nine and the Politics of Race. Race Today Review, 1980.