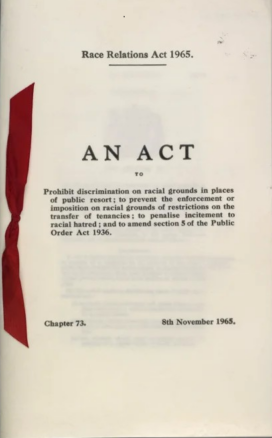

In November 1965, Britain made history. For the first time, Parliament recognised that racism was not just a private prejudice but a public wrong that demanded the law’s attention. The Race Relations Act was modest in scope and weak in enforcement, yet it marked the beginning of a legislative journey towards racial equality in public life. The Act outlawed discrimination in public places on the grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins. Its powers were limited, but its symbolism was profound. For many Black and Asian Britons, who had long endured exclusion in housing, jobs and daily life, it was recognition — not justice, but at least acknowledgement.

A Changing Nation

A Changing Nation

The story of the Act cannot be told without the story of post-war Britain. In the late 1940s and 1950s, tens of thousands of men and women from the Caribbean, South Asia and West Africa came to the UK, many at the invitation of the British government, to help rebuild a nation scarred by war. They worked in hospitals, factories, transport and public services.

They arrived as British citizens, steeped in British values, yet their welcome was cold. Landlords turned them away. Employers dismissed applications on sight. Pubs, hotels and restaurants refused service. The infamous signs — “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” — were not legend but reality. At the time, none of this was illegal. The courts would not intervene. The state stayed silent, clinging to the belief that racism was an American problem, not a British one.

Racism Exposed

The injustice was not new. In 1943, the celebrated cricketer and barrister Learie Constantine took London’s Imperial Hotel to court after it refused him and his family a room because of their colour. He won the case, but the ruling was narrow and offered no wider protection. His experience showed that racial discrimination in Britain pre-dated the Windrush era, placing the 1965 Act within a much longer timeline.

That illusion of Britain being free from racism collapsed again in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Notting Hill riots of 1958, when white mobs attacked Caribbean residents, exposed the violence on Britain’s streets. The 1964 Smethwick by-election, fought with openly racist slogans, showed prejudice was not only social but political.

At the same time, grassroots resistance was growing. In 1963, the Bristol Bus Boycott — led by civil rights pioneers Paul Stephenson, Roy Hackett and others — challenged a company’s refusal to hire Black or Asian bus crews. Inspired by the Montgomery Bus Boycott in America, the campaign mobilised the whole city, winning national headlines and forcing the company to reverse its policy. Stephenson also made waves when he refused to leave a Bristol pub that denied him service because of his colour — an act of defiance that exposed everyday discrimination in stark terms.

International events added pressure. The civil rights movement in the United States was reshaping global attitudes, and campaigners in Britain took note. In early 1965, the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) was formed, bringing together activists, clergy, lawyers and community leaders. CARD drew inspiration from figures such as Claudia Jones — the Trinidadian journalist, publisher and organiser who had founded The West Indian Gazette and the early Notting Hill Carnival before her death in 1964. CARD provided a united voice, insisting that Britain needed its own laws to protect minorities from racial injustice.

The First Step

26 March 1969

Labour’s 1964 election victory created an opening. Harold Wilson’s government, aware of mounting tensions, tasked Home Secretary Frank Soskice with introducing the Race Relations Bill. The debate in Parliament was heated. Supporters argued that the law was overdue. Opponents protested that it threatened “freedom of association” — a coded defence of the right to discriminate in one’s home, business or club. Others dismissed it as unenforceable or unnecessary, claiming Britain had no real “colour problem.”

Despite resistance, the Bill passed. In August 1965, the Race Relations Act made it illegal to deny service in public places such as hotels, pubs, restaurants and transport on the grounds of race, colour or ethnic origin. It also outlawed the publication of material likely to incite racial hatred.

To oversee complaints, the Act created the Race Relations Board. But the Board’s role was conciliatory, not punitive. It could investigate and advise, but it had no power to enforce decisions or impose penalties. Housing, jobs and education — the areas where discrimination cut deepest — were left untouched.

Campaigners quickly recognised these weaknesses. They had not won the protections they needed, but they had secured something important: the first admission by the state that racial discrimination was wrong. It was a start — and starts matter.

Building on the First Step

The shortcomings of the 1965 Act were obvious, and pressure for reform mounted quickly. In 1968, Parliament extended protections to cover housing, employment and the provision of goods and services — directly addressing the daily struggles of finding a home or securing work. Still, enforcement was weak.

By 1976, further reform created the Commission for Racial Equality, with wider powers to investigate, support victims and hold institutions accountable. The Commission became a visible symbol of the state’s responsibility to tackle racism, even if its resources were often stretched thin.

Over time, Britain’s anti-discrimination framework widened further. The Equality Act 2010 consolidated earlier laws, protecting not only against racial discrimination but also against prejudice on grounds of religion, gender, sexuality, age and disability. The journey that began with the 1965 Act had grown into a comprehensive — if still imperfect — attempt to legislate fairness.

It is important to remember that none of this began in Westminster alone. It was demanded, shaped and forced onto the political agenda by ordinary people: tenants denied housing, workers turned away from jobs, families refused service, and campaigners who refused to remain silent.

Figures like Paul Stephenson, Roy Hackett, Claudia Jones and the leaders of CARD represent countless others whose names are less known but whose persistence created change. Their demands gave the 1965 Act life, and their disappointment with its limits ensured that stronger laws followed.

An Unfinished Struggle

Looking back, it is tempting to judge the 1965 Act by its failures. It did not end racism. It did not guarantee equality. It left too many people unprotected. But to dismiss it entirely is to overlook its role in changing the political and legal landscape. The Act planted a marker: that racial discrimination, however limited the law’s reach, was unacceptable in British society. That marker still stands. It reminds us that rights are not handed down as gifts but won through struggle and secured by vigilance.

Sixty years later, the language of legislation has evolved. So too has the public debate. Yet the work of racial equality remains unfinished. Reports such as the Macpherson Report (1999) into the murder of Stephen Lawrence and the Windrush Lessons Learned Review (2020) show how deeply racism remains embedded in Britain’s institutions. Disparities continue in policing, health, education and employment.

Marking this 60th anniversary is not simply about commemoration. It is about honouring those who fought for the Act by recognising how much more remains to be done. The Race Relations Act of 1965 did not close the chapter on racism in Britain. It opened a new one: a chapter where the law could no longer excuse discrimination but was required, however imperfectly, to challenge it. It was not the end of the struggle. It was the beginning of another — rooted in rights, recognition and the long, unfinished demand for justice.

Further Reading & References

- Paul Stephenson, Memoirs of a Black Englishman (2001) — a first-hand account from one of the Bristol Bus Boycott leaders.

- David Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016) — a definitive exploration of Britain’s long Black history.

- Home Office, The Race Relations Act 1965: Parliamentary Debates — Hansard records of the Act’s passage through Parliament.

- Claudia Jones, Selected Writings (compiled essays, 1988) — insights from the journalist and activist who shaped early anti-racist movements in Britain.

- The Macpherson Report (1999) — The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, HMSO.

- Windrush Lessons Learned Review (2020) — Independent review led by Wendy Williams.

- The Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) Archives, Black Cultural Archives, London.

- BBC Radio 4 Documentary, The Race Relations Act at 50 (2015) — retrospective analysis and interviews with key figures.