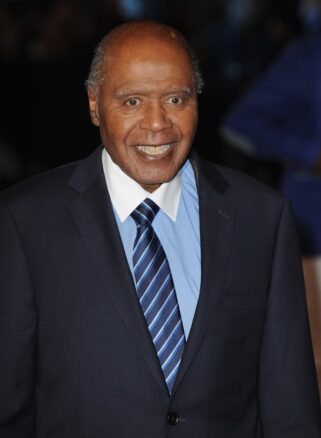

On a damp spring morning in 1963, Bristol’s buses rolled through the city half-empty. Passengers stayed away. The boycott had begun. At its heart was a young youth worker named Paul Stephenson — calm, determined, and unwilling to accept that a man’s skin colour should dictate his place in Britain. He was not the kind of man who sought fame or applause. He did not raise his voice to dominate a room, nor court the cameras. Instead, he stood his ground with quiet dignity. His power was in the way he refused to bend. He was, in every sense, a quiet revolutionary.

A Childhood Shaped by Difference

Paul Stephenson was born on 6 May 1937 in Rochford, Essex, the only child of a West African father and a white British mother. When the Second World War broke out, he was evacuated and spent seven years in a children’s home in Great Dunmow. It was there he first experienced what it meant to be “different.” He grew up being constantly reminded that he did not quite belong. The taunts of other children, the raised eyebrows of strangers, the subtle exclusions — they marked his early years. Yet instead of turning that difference into bitterness, he transformed it into resilience.

As a teenager, he returned to London and attended school in Forest Gate, where he was often the only Black pupil. Later, he joined the Royal Air Force in 1953, serving for seven years until 1960, including time posted in Germany. The RAF gave him structure and pride, and for the first time he felt himself part of an institution where discipline, rather than prejudice, set the terms. Those years shaped his confidence and his sense of himself as a citizen with rights and responsibilities.

The Road to Bristol

After leaving the RAF, Stephenson studied at Heriot-Watt College in Edinburgh before training as a youth and social worker. In 1962 he moved to Bristol to take up a post as the city’s first Black social worker. Bristol, like many British cities, had seen a large influx of Caribbean and African migrants after the war. They had come to rebuild the country, to drive its buses, staff its hospitals, and work in its factories. Yet despite their labour, they were often treated as unwelcome outsiders.

The Bristol Omnibus Company made its position clear: Black and Asian men could clean buses, but they would never be allowed to drive them or take tickets from passengers. The local branch of the Transport and General Workers’ Union supported this “colour bar.” For the company, it was simple: white drivers and conductors, Black cleaners. For Stephenson, it was intolerable. Inspired by the civil rights movement in the United States — where Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks had shown the power of resistance — he saw that change in Britain would also come from ordinary people refusing to accept injustice.

The Bristol Bus Boycott

On 29 April 1963, the Bristol Bus Boycott began. Stephenson, working alongside community leaders Roy Hackett, Owen Henry, Audley Evans, and Guy Bailey, organised a campaign urging Bristolians to stop using the buses until the company relented. The boycott caught the imagination of the press. Newspapers across the country reported the story. National politicians, including Harold Wilson, were forced to respond. Within just over 60 days, the company lifted its ban.

It was a turning point. Britain could no longer pretend that racism was only an American problem. Here, on the streets of Bristol, the colour bar had been defeated. And yet, Stephenson himself never claimed the limelight. He described the boycott as a collective victory, insisting that it belonged to the community, not to him. His modesty was not false humility; it was the core of who he was. For him, the cause always came before the man.

He would later reflect: “Every generation has a duty to fight against racism, otherwise it will find its way into our country and into our homes.”

Quiet Acts of Defiance

The boycott was only the beginning. In 1964, Stephenson walked into the Bay Horse pub in Bristol and ordered a drink. The landlord snapped back: “We don’t want you black people in here — you are a nuisance.” Where many might have left in weary silence, Stephenson refused to move. His calm defiance turned a small act of everyday prejudice into a national headline.

The case went to court and once again exposed Britain’s racial inequalities. It also fuelled the growing demand for legal protection against discrimination. Within a year, Parliament passed the Race Relations Act 1965, the first law in Britain to make racial discrimination in public places unlawful. Stephenson’s defiance had not only made a stand; it had shaped the law.

A Life of Service

Stephenson’s later career reflected his deep commitment to fairness. He worked in housing, education, and community development. He became a member of the Commission for Racial Equality and advised both local and national government on race relations. His goal was always the same: to create a Britain where people were judged by their ability and character, not by the colour of their skin.

Those who knew him remember a man of warmth and humour. He was approachable, a good listener, and quick to encourage others. But beneath that gentleness lay unshakeable resolve. He was not a man to be intimidated. He would always stand his ground, even if he stood alone.

Recognition and Later Years

Recognition came later in life. In 2009, Paul Stephenson was awarded the OBE for his services to equal opportunities and community relations. For many, the honour was long overdue. By then, he had already become a symbol of Britain’s civil rights movement.

In his later years, he lived quietly, battling Parkinson’s disease and dementia. Yet even as his health declined, his legacy continued to inspire. Young campaigners in Bristol and beyond looked to his story as proof that ordinary citizens could change the direction of history.

Paul Stephenson passed away on 2 November 2024, aged 87. Tributes poured in from across the country. Community leaders, politicians, and ordinary citizens alike spoke of his courage and humility. In Bristol, vigils were held. Murals were painted. His name was spoken with reverence — the quiet revolutionary who had stood up and said no.

The Quiet Power of Refusal

Paul Stephenson’s life shows us that history is not only written by those who seek the stage, but also by those who quietly refuse to move. He was never interested in fame. He did not shape his life around titles or honours. What he wanted was fairness, the simple dignity of being treated as an equal citizen.

That dignity was not just for himself, but for his community. When he stood firm in a Bristol pub, when he called on a city to boycott its buses, he was saying: we belong here. His actions carried a message that Britain could no longer ignore — that its Black citizens were not visitors, but part of the fabric of the nation.

He matters because he reminds us that courage does not always roar. Sometimes it whispers no, calmly, firmly, and changes the course of a city, a law, a country. He matters because his story belongs not only to Bristol, but to Britain. And he matters because his life is a challenge to us all: to find the courage to stand, as he did, quietly and unshakably, against what is wrong.