There is a rhythm in history, a steady beat born of people who refuse to bow. A. Philip Randolph’s rhythm was organisation — built brick by brick with discipline, persistence, and an unshakeable belief in dignity. He was American by birth, but his message crossed the ocean. When he came to Britain, it landed with force in the workplaces and churches of Brixton, Birmingham and Manchester.

Born on 15 April 1889 in Crescent City, Florida, Randolph was the son of a preacher and a seamstress. His father mended suits by day and preached at night; his mother stitched fabric. From both he absorbed the lesson that honest labour was sacred. From the pulpit he learned another truth: every soul has value, and to deny that value is to deny justice.

By 1911 he had made his way to Harlem, alive then with jazz, Shakespeare and fierce debate. Tall and commanding, Randolph could fill a hall unaided. He carried Shakespeare’s grandeur in his cadence and socialism’s clarity in his purpose. He became convinced of something radical: that Black freedom and workers’ freedom were one and the same.

The railways were his proving ground. The Pullman porters — almost all Black men — carried luggage, polished shoes, smiled for passengers. Their service was efficient, polite, and invisible. Behind the uniform was exploitation: low pay, long hours, no respect. In 1925 Randolph began to organise them into the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The company spied on them, threatened them, dismissed them. White-led unions turned their backs. Yet Randolph persisted. For twelve years he held the line. In 1937 the company recognised the Brotherhood; wages rose, hours shortened. It was more than a contract. It was dignity in writing: the first Black-led union recognised by a major American corporation.

“Salvation for a race, nation or class must come from within. Power is the flower of organisation.” — A. Philip Randolph

In 1941, he demonstrated another lesson: sometimes you win not by marching, but by threatening to march. As America prepared for war, Black workers were excluded from defence jobs. Randolph announced a March on Washington. Tens of thousands would descend on the capital. President Franklin Roosevelt, terrified of the optics, summoned Randolph. Calm, unyielding, Randolph refused to back down. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, banning discrimination in defence industries. The march never took place, but the victory was real — proof of the power of a credible threat.

Randolph’s reputation travelled across the Atlantic. In the 1950s and early 1960s, he visited Britain. His name preceded him: the man who had made presidents move. He spoke to trade unionists, who recognised in him a kindred spirit. He spoke to church leaders, who heard his conviction that justice was not abstract but a daily demand. And in Britain’s Black communities — especially among the Windrush Generation, who faced signs declaring “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” — his message resonated. Dignity could be demanded. Dignity could be won. His example became a quiet influence, reminding campaigners here that their struggle was part of a global movement.

By 1963, Randolph was again at the centre of history. At seventy-four he stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, opening the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He believed civil rights without economic rights meant little: “What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?” he asked. That march is remembered for Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, but it was Randolph’s vision — jobs and freedom together — that gave it its power. He told the crowd they were the “advanced guard of a massive moral revolution.”

“Justice is never given; it is exacted.” — A. Philip Randolph

Randolph lived to see both victories and reversals. He saw civil rights laws passed, desegregation achieved, trade unions strengthened. But he also saw racism mutate, poverty persist, and he knew the struggle would outlast him. He died in 1979, leaving not just memory but instruction: organise, persist, demand dignity.

Britain felt his influence. His visits were not ceremonial. They reminded Black Britons that their fight for equality at work, in housing and in civic life, was linked to a wider global struggle. If a man could stare down Roosevelt and Kennedy, then British ministers and employers could be made to move too.

Work today is as precarious as in Randolph’s time. The gig economy, zero-hours contracts, migrant workers treated as disposable. He would recognise it all. And he would remind us that exploitation is not destiny. That power comes from organisation. That dignity, once demanded, cannot be denied.

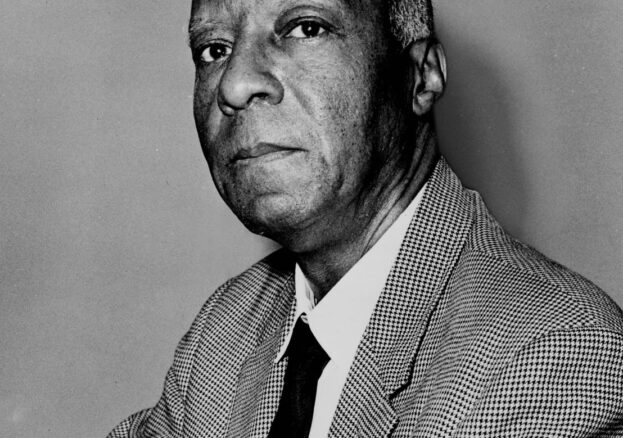

There is still that photograph: Randolph, stern, unyielding, unsmiling. A reminder that sometimes the most radical act is simply to refuse to bow. To look power in the face and insist: I am worthy. He stood firm in power and pride — and in doing so, he showed both America and Britain that dignity is not a gift. It is a right. –

Further Reading & References

Books

- A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait by Jervis Anderson (1973)

- A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement by Paula F. Pfeffer (1990)

A. Philip Randolph: A Life in the Vanguard by Andrew E. Kersten (2006) - Reframing Randolph: Labor, Black Freedom, and the Legacies of A. Philip Randolph edited by Andrew E. Kersten & Clarence Lang (2015)

Online Resources