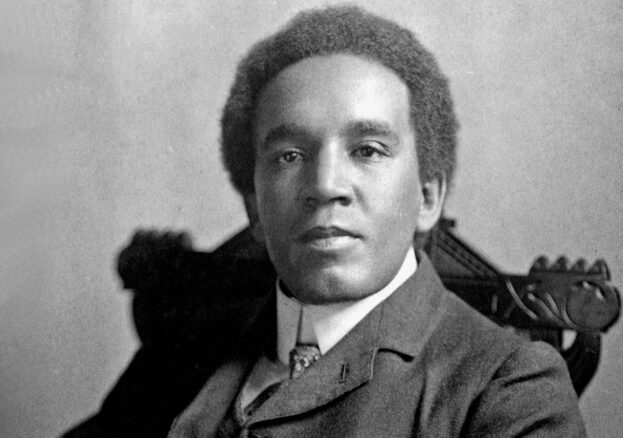

At the turn of the twentieth century, concert halls across Britain and beyond echoed with the music of a young Black composer whose genius drew comparisons with Brahms and Dvořák. His name was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a London-born prodigy who overcame prejudice to create works of extraordinary beauty, depth and power. For a brief time, he was one of the most celebrated composers of his generation. Though he died tragically young, his music and legacy still resonate, offering a reminder of both the brilliance and the barriers faced by Black artists in Britain’s past.

Coleridge-Taylor was born in Holborn, London, in 1875, the son of Daniel Taylor, a doctor from Sierra Leone, and Alice Hare Martin, an Englishwoman. His father returned to Africa before Samuel’s birth, leaving his mother to raise him in Croydon. It was a modest upbringing, but Alice recognised her son’s extraordinary gift. She saved to buy him a violin, and by the age of fifteen he had won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music. There, he studied composition under Charles Villiers Stanford, quickly establishing himself as one of the institution’s most promising talents.

In an era when Britain’s classical music world was overwhelmingly white and upper-class, Coleridge-Taylor’s presence was remarkable. His talent could not be denied. His early works, including a symphony and chamber pieces, were praised for their lyrical intensity. But it was his cantata trilogy The Song of Hiawatha (1898–1900), inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, that catapulted him to fame. When the first part, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, premiered at the Royal College of Music, it was an instant triumph. The critic Joseph Bennett wrote in The Daily Telegraph: “It is long since we have heard anything that so moved the audience… The young composer has a real message, and he delivers it with power and freshness.” The audience demanded the work be encored — a rare honour — and Coleridge-Taylor was suddenly a name on everyone’s lips.

For decades afterward, The Song of Hiawatha became a fixture of British musical life. Staged annually at the Royal Albert Hall with full chorus, orchestra and elaborate costumes, it drew audiences as large and loyal as those for Handel’s Messiah. For many concertgoers, Coleridge-Taylor’s music defined the Edwardian era’s soundscape. Yet while his compositions were celebrated, the composer himself often faced the casual racism of the time. He was sometimes referred to in the press by his race before his art, labelled “the African Mahler” or “the Black Dvořák.” These comparisons were meant as praise, but they also reflected a society that struggled to see him simply as Coleridge-Taylor: a composer in his own right.

Coleridge-Taylor never forgot his African heritage. Inspired by American writer and activist W. E. B. Du Bois, whom he met in London, he developed a strong interest in Pan-African ideas. Du Bois later wrote of him: “Here is a man who has made the world listen to the music of his race… He has taken the sorrow songs of our people and given them a new voice.” Coleridge-Taylor travelled to the United States three times, where he was welcomed with extraordinary warmth by African American communities. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to the White House — a symbolic moment at a time when racial segregation in America was at its height. For Black musicians and audiences in the United States, he was living proof that excellence could flourish against all odds.

Despite his fame, Coleridge-Taylor never achieved financial security. Like many composers of his time, he was paid a flat fee for his works and did not benefit from royalties. His greatest success, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, brought him just fifteen guineas, while publishers went on to profit handsomely from its popularity. Colleagues campaigned for him to receive a civil pension, but before meaningful support could be arranged, tragedy struck. In 1912, weakened by pneumonia, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor collapsed on a train platform and died shortly afterwards. He was just thirty-seven.

The news of his death shocked the musical world. Crowds lined the streets of Croydon for his funeral, and he was mourned not only in Britain but across the Atlantic. The New York Times obituary described him as “a composer of great individuality, whose untimely death is a loss to music of all races.” In recognition of the injustice he had faced, the British government granted his widow, Jessie, a pension from the Civil List — a rare honour at the time.

Coleridge-Taylor left behind a remarkable body of work: orchestral pieces, chamber music, songs, and choral works that continue to be rediscovered today. His compositions blended the traditions of European classical music with rhythms, melodies and themes inspired by African and African American heritage. He stands as a forerunner of composers who sought to bring diverse cultural voices into classical form.

For Black History Month, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s life invites reflection on talent, identity and recognition. He showed that brilliance can emerge from unexpected places, that barriers of race and class can be challenged through creativity, and that art has the power to connect worlds. Though history has not always given him the recognition he deserves, his music endures as testimony to a man who dreamed in sound, and who gave voice to a heritage too often silenced.

Further Reading & Sources

- Jeffrey Green, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a Musical Life (2005)

- Joseph Bennett, The Daily Telegraph review of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast (1898)

- W. E. B. Du Bois, essays and letters on Coleridge-Taylor (1904–1912)

- New York Times, obituary (1912)

- The Coleridge-Taylor Society archives

- BBC Radio 3 documentaries on Coleridge-Taylor