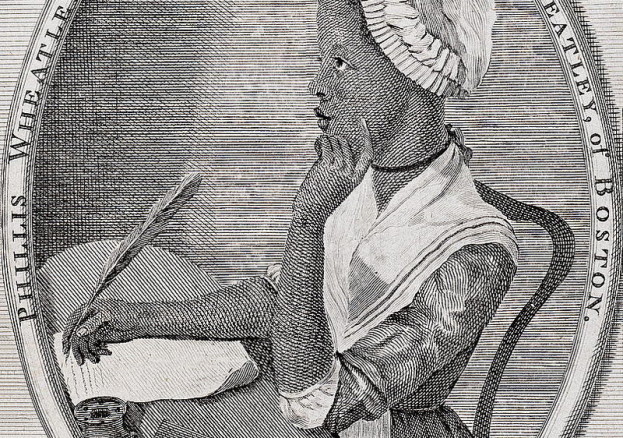

Phillis Wheatley (original birth-name unknown) was born somewhere in West Africa sometime during 1753. The exact place and date of birth is unknown as there are no known surviving records of her initial appearance.

However, we do know though ship manifest records; ‘The Phillis’ that she was kidnapped at the age of eight and was taken to America where she was sold in Boston to the Wheatley family. Here she became the enslaved servant of her owners wife; Susanna Wheatley.

The origins of her name are a combination of the boat she had been sold from; the ‘Phillis’ and the owners family name; ‘Wheatley’.

As a servant, it is said Phillis was treated well, as her owners were known to be a progressive thinking family. Despite being owned by the family, they did educate Phillis to the point where she was literate in English, Greek and Latin- allowing her to write her first poem at aged 14, titled; ‘To the University of Cambridge, In New England’.

It is said that the family nurtured Phillis’ talents, showing off her skills to friends and family, who in turn encouraged her to pursue an education and develop her writing.

By the age of 20, Phillis was no longer tied to the family estate, and in 1772; she was tasked in accompanying the eldest son; Nathaniel Wheatley to England, as the family thought it would improve her ailing health as well as improve her chances of becoming a published poet.

Within a year, Phillis was published, making her the first African-American and first African-American Woman to be published on the release of her first volume of poetry in 1773.

Within these poems, Wheatley regularly expressed in great detail what it was like to be enslaved, most noticeably, the shock such an experience and how it presents itself.

However, Phillis would not limit her voice to paper, and despite women being systematically disenfranchised in the 18th Century, Phillis Wheatley regularly spoke out against Slavery in public meetings.

In 1774, Phillis Wheatley wrote a letter to Reverend Samson Occom, commending him on his ideas and beliefs of how the slaves should be given their natural born rights in America. Wheatley also exchanged letters with the British philanthropist John Thornton, who in turn discussed Wheatley and her poetry in his correspondence with John Newton

1775 saw a copy Phillis Wheatley’s poem entitled, “To His Excellency, George Washington” sent to him. This lead to Washington inviting Wheatley to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which she did in March of 1776.

John Wheatley, Phillis’ legal master, legally emancipated Phillis in 1778; allowing Phillis to marry John Peters, another free Black person and grocer three months later.

However, despite being able to live the dream of being free, the staunchly racist environment that America had incorporated during the late 1700’s meant the couple struggled with ill-health, a low income and poor work; causing the death of two of their infant children.

Wheatley wrote another volume of poetry but was unable to publish it because of her financial circumstances due to the loss of patrons after her emancipation and the literary competition from the Revolutionary War. However, some of her poems that were to be published in that volume were later published in pamphlets and newspapers.

The financial situation for the Wheatley-Peters family worsened and in 1784, Phillis’ husband was imprisoned for the accumulation of his debts, forcing Phillis to work as a scullery maid at a boarding house to support them.

However, this would not be enough to sustain the family and both Phillis and her infant son would die on December 5, 1784, at the age of 31.

In 1789, after the death of the poet, one of her poems was published by a London newspaper;

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate,

Was snach’d from AFRIC’s fancy’d happy seat;

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parents’ breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no mis’ry mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belove’d;

Such-such my case; and can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

Legacy

Phyllis Wheatley may be the first published African-American Poet, but her legacy has been overshadowed by Male abolitionists such as Cugoano and Equiano as their later lives were not overshadowed by crippling poverty and a drastic loss in readership.

However, to conclude that Phillis’ success was solely dependent on the resources her previous owners could spare would be an understatement to her achievements and talents as a young, Black Woman in the 18th Century.