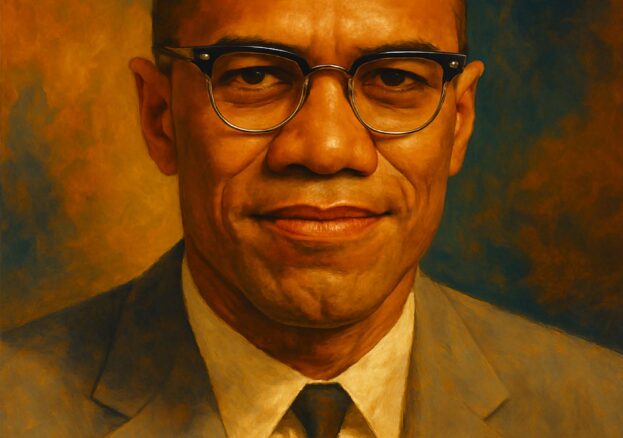

Malcolm X was assassinated on 21 February 1965 in New York City, at just 39 years old. His life ended abruptly, but his words continue to reverberate—not only in the United States but powerfully in Britain, where activists, community leaders, and ordinary people found in his voice a model of dignity and resistance. Reflecting on Malcolm X in 2025 is less about revisiting the past than recognising that his vision remains acutely relevant to Black British struggles for equality and justice today.

Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925, his early life was shaped by trauma and injustice. His father’s death and his mother’s institutionalisation plunged the family into disarray. At 20, Malcolm found himself in prison—a turning point that changed the course of his life. He later reflected: “People don’t realise how a man’s whole life can be changed by one book.” For him it was not one book but many—histories, philosophies, and religious texts devoured in a cell that became his classroom. Through reading and reflection, he remade himself. Through the Nation of Islam, he discovered a framework to explain the racism he saw all around him.

As Minister Malcolm X in the 1950s, he became a striking, indomitable voice. His speeches cut through the polite fictions of American democracy. While Martin Luther King Jr. offered the vision of a dream, Malcolm confronted the nightmare. “You can’t separate peace from freedom because no one can be at peace unless he has his freedom,” he declared. His famous call for liberation “by any means necessary” was not a reckless endorsement of violence, but a principle of assertive self-defence and self-respect. To many white Americans, this was threatening militancy. To many Black Americans—especially those in the neglected urban North—it was the first time they heard a leader articulate their anger and affirm their dignity.

Malcolm’s words travelled far beyond America. In Britain, where post-war Caribbean migrants faced open hostility in housing, employment, and policing, his message struck a deep chord. Young Black Britons in the 1960s discovered his speeches in pamphlets and recordings that circulated through community centres. His example gave shape to a new confidence: the idea that Black people need not wait patiently for respect, but should claim dignity for themselves. The British press often caricatured him as a dangerous radical, but in Brixton, Birmingham, Nottingham, and beyond, he was heard as a brother in struggle.

Malcolm X visited Britain twice—both times brief, yet historic. His first visit came in December 1964, when he addressed the Oxford Union on the motion “Extremism in the defence of liberty is no vice.” Calm, articulate, and cutting, he challenged Britain’s self-image as a tolerant empire. “I’m not here to argue against extremism in defence of liberty,” he told the students. “I’m here to say that I don’t believe it is extremism.” His speech resonated with those who recognised that Britain, for all its claims to fairness, was deeply implicated in global racial inequality.

His second visit followed in February 1965, just nine days before his assassination. He travelled to Smethwick, near Birmingham, invited by Avtar Singh Jouhl of the Indian Workers’ Association. Smethwick had recently seen one of Britain’s most openly racist election campaigns, where supporters of the Conservative candidate used the slogan: “If you want a n**r for a neighbour, vote Labour.” Malcolm walked down Marshall Street, where housing segregation was enforced by informal colour bars. He said: “I have come because I am disturbed by reports that coloured people in Smethwick are being treated badly,” and added, “This is worse than in America.” He later spoke at the University of Birmingham and the London School of Economics, engaging students and activists.

These visits were fleeting, but their impact was lasting. They linked the Black freedom struggle in America with Britain’s own battles over race and equality. For young Black Britons, Malcolm’s presence was electrifying. It showed that their struggles were not isolated but part of a global movement. British activists who would later form groups like the British Black Panther Movement drew directly on his insistence on pride, self-organisation, and resistance. Darcus Howe, one of the movement’s leading figures, recalled that Malcolm X’s words helped inspire a generation to stand tall in a country that too often sought to belittle them.

Malcolm’s influence was also felt in campaigns against discriminatory policing in Britain. The “sus laws”—stop-and-search powers disproportionately used against Black youth—provoked growing anger from the late 1960s. Activists often invoked Malcolm’s defiant words: “If someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery.” While few embraced literal violence, the quote became a symbol of refusal: a rejection of passivity in the face of harassment. For many, his language was an empowering reminder that they did not need to endure injustice quietly.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Malcolm’s image had taken root in British popular culture. His speeches were reprinted in Black community newspapers; his face appeared on posters in student rooms and community centres; his autobiography, co-written with Alex Haley, was passed from hand to hand. Its raw honesty—charting his life from hustler to revolutionary—spoke powerfully to those trying to navigate racism in Britain. “The future belongs to those who prepare for it today,” Malcolm had said. For many Black Britons, that line became a call to action: to educate themselves, to organise, to prepare for a better tomorrow.

Malcolm’s evolution in his final year also matters for his British legacy. His break with the Nation of Islam, his pilgrimage to Mecca, and his embrace of a more global, inclusive vision showed him moving beyond separatism. In Mecca he wrote: “I have never before seen sincere and true brotherhood practiced by all colors together, irrespective of their color.” This experience did not dilute his critique of racism but expanded it—connecting the Black struggle in America with anti-colonial movements in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. For Britain, with its imperial history and diverse postcolonial population, this message carried special force. His vision of solidarity across borders spoke to communities who were themselves the children of empire, carving out new identities in the heart of the old metropole.

In Britain today, Malcolm X’s voice can still be heard in debates about race and justice. When young people march against police violence, when campaigners call for the decolonisation of education, when communities assert pride in their heritage, his words echo. His insistence on truth remains compelling: “I am for truth, no matter who tells it. I am for justice, no matter who it is for or against.” In an age of widening inequality and contested history, his radical honesty feels as necessary as ever.

At the same time, Malcolm’s memory is contested. Some dismiss him as too militant; others romanticise him as a symbol without grappling with the complexity of his thought. But the anniversary of his death is a reminder to engage with the real Malcolm X—not the caricature of rage, nor the saintly icon, but the man who evolved, admitted mistakes, and grew into a thinker of global importance. His legacy lies in that journey: the capacity to transform, to adapt, to expand the struggle without ever abandoning principle.

For Black History Month 2025, with its theme of Standing Firm in Power and Pride, Malcolm X offers a model that is both demanding and inspiring. He stood firm: refusing to bend to the comforts of gradualism, insisting on the urgency of justice. He embodied power: not the power of wealth or office, but the power of intellect, courage, and clarity. And he radiated pride: in his heritage, in his people, in the right to live free of degradation. Sixty years after his assassination, Britain still needs that message.

Malcolm X’s death was meant to silence him. Instead, it amplified him. His speeches remain on playlists, his words are quoted in classrooms, his face appears in murals from Brixton to Smethwick. He belongs not only to American history but to the world—and in Britain, where racism and resistance continue to shape lives, his echo is unmistakable. To remember Malcolm X today is to recommit ourselves to the struggle he so fiercely embodied: a struggle for truth, for justice, and for the dignity of all people.

References & Further Reading

- Malcolm X & Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

- Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (2011)

- Saladin Ambar, Malcolm X at Oxford Union: Racial Politics in a Global Era (2014)

- Robin Bunce & Paul Field, Darcus Howe: A Political Biography (2014)

- Kennetta Hammond Perry, London Is the Place for Me: Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race (2015)