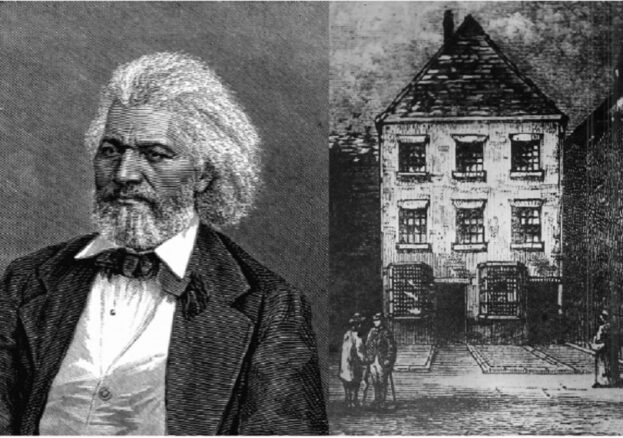

Frederick Douglass drew himself up to his height of just over 6 feet, looked out over the packed audience of over 1,000 – mostly millworkers – and vociferously and eloquently described his life as a slave in the United States of America. It was October 10, 1846, and Douglass had just been warmly introduced by John Bright, a British Member of Parliament. Even at a young age, Bright had already emerged as one of the most powerful British speakers against slavery. Not surprisingly, his asking Douglass to speak had created a sold-out house in the Public Room on Baillie Street in Rochdale, Lancashire, England.

Frederick Douglass was 28 years old and had just published his first book:”Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave.” Because the book was an instant bestseller in the U.S., and because the press identified the public places where Douglass spoke, Douglass was at grave risk of immediate arrest as a fugitive slave. He fled to Britain after his owner, Thomas Auld of Maryland, had announced that he intended to capture Douglass and return him to forced slavery. William Lloyd Garrison, the leading American Abolitionist, had accompanied Douglass to Rochdale, and together with Douglass, spoke at each of the October meetings there.

Douglass used his time in England to educate the engaged Rochdale and British audiences about his life as a slave and slavery itself in the United States. He spoke at the Public Hall in Rochdale five times in 1846, between October 10 and 14, and twice more on November 10 and 11. On October 12, Douglass returned to Manchester to speak to 4,000 people at the Free Trade Hall, and then returned to Rochdale.

Surely among the audience at the Public Hall in Rochdale that night and during the other speeches which Douglass gave that week in Rochdale, were some of the founders of the first modern co-op. The tiny store opened by the Rochdale Pioneers at 31 Toad Lane was about a three-minute walk away from the Public Room on Baillie Street. All of the original 28 members of the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society were heavily engaged in the social and political change of that era. Every Sunday, many of Rochdale’s co-op founders and members attended the non-conformist churches, such as Methodist, Unitarian, and Baptist chapels. Here, they would have heard sermons on the evils of slavery. These local activists had started the Co-op in 1844, to change their daily circumstances. Every day at work in the mills or walking on its streets, the Rochdale Pioneers were recruiting other millworkers to join their co-op.

John Bright was an early supporter of the “self-help” philosophy of the Rochdale Pioneers and occasionally spoke in Parliament about the accomplishments of his local Co-op. Bright supported changes in the law that gave co-operatives greater financial power. Additionally, Bright spoke highly of the co-ops’ ability to be democratic while running a business. Bright noted in his 1854 diary that he was to visit the co-op on Toad Lane to check on its progress. Bright used the example of the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society to sway other members of parliament in favor of extending the vote to working men.

Bright’s brother, Jacob Bright, was also a strong supporter of co-operatives. In the 1850s he was appointed as an arbitrator of the Co-operative Manufacturing Society and the co-operatively run Corn Mill. Subsequently, Jacob Bright became the first elected Mayor of Rochdale.

During his almost three-year stay in Britain (1845-1847), Douglass gave roughly 300 public speeches in many different towns and cities in Britain. Many of his speaking engagements and stays were hosted by a strong network of Quakers, John Bright, being one of them. Bright had arranged for Douglass to speak in Rochdale on seven different occasions in 1846 alone. Douglass was also a regular guest at “One Ash,” the Rochdale home of John Bright and his family. In “The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,” page 235, Douglass writes about his first visit to England (1845-1847), “I was, besides, a welcome guest at the home of Mr. Bright in Rochdale and treated as a friend and brother among his brothers and sisters.”

Beginning in August of 1846, Ellen Richardson, a Newcastle Quaker, engaged in raising funds from a circle of Quakers to buy Frederick Douglass out of slavery. As a result of Douglass’ stay with John Bright in Rochdale, Bright immediately contributed one-third of the money needed to purchase Douglass from his American slaveholder. In October of 1846, Douglass arrived in Rochdale a fugitive slave. With Bright’s large contribution, however, Douglass left Rochdale about to become a free man. Ellen Richardson wrote that with the generous gift from Bright, they were certainly going to have the funds they needed to buy Douglass’s freedom from slavery.

By December 1846, Bright and the other Quakers learned that the sale was almost complete. Towards the middle of December, Frederick Douglass learned by steamship mail that as of December 12, 1846, Douglass was no longer legally a slave in the USA, and his papers of manumission had been confirmed.

On December 22nd, 1846, Douglass wrote a reply to a letter written by Henry C. Wright on December 12th. Wright was a fellow American abolitionist who occasionally spoke on the same platform as Douglass. Douglass was cautious about being allied with him as Wright was a fiery speaker with more radical views than Douglass. Wright had written to Douglass severely critiquing him for allowing people to buy him as a slave.

From the content of each of the letters, it is evident that both Wright and Douglass knew that Douglass was being freed. At the time, Douglass was staying twelve miles away from Rochdale at 22 St Ann’s Square, Manchester.

Frederick Douglass remarked on March 30, 1847, at a farewell banquet at the London Tavern in London:

“I do not go back to America to sit still, remain quiet, and enjoy ease and comfort. . . I glory in the conflict that I may hereafter exult in the victory. I know that victory is certain. I go, turning my back upon the ease, comfort, and respectability which I might maintain even here. . . Still, I will go back, for the sake of my brethren. I go to suffer with them; to toil with them; to endure insult with them; to undergo outrage with them; to lift up my voice in their behalf; to speak and write in their vindication; and struggle in their ranks for the emancipation which shall yet be achieved.”

In his conclusion, Douglass states, “I came here a slave, but I go back free.”

On April 2, 1847, Douglass stayed with John Bright in Rochdale the day before leaving England to return to America, finally a free man.

Booker T. Washington wrote of the stay of Douglass as the guest of John Bright and his sisters. “From no one in England could Douglass have received a more gracious welcome and friendly benediction than from this great commoner. “Frederick Douglass: A Biography by Booker T. Washington,” (p 65). Originally published: Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs, 1906.

Douglass sailed from Liverpool early on Sunday, April 4, 1847, and landed in Boston, Massachusetts, arriving in his home in Lynn, MA.

The linking of Frederick Douglass, John Bright, Rochdale, and the first modern co-op began in 1846. The link between co-operatives and the campaigns against slavery, and for civil rights continues strongly to this very day and for eons to come.

This linkage can be divided into two different eras;

1. Anti-Slavery and Co-ops

Frederick Douglass’ sojourn in Britain from 1845-1847, occurred during the same years that consumer and worker co-operatives were being born all over Britain. The Chartist movement, a working-class movement meant to make the political system more democratic, might have been stalled by Parliament, but the struggle for local democratic and social change carried on in the form of democratic co-operatives. Many of the British Chartist leaders who welcomed Douglass to speak were also engaged in building different types of co-operatives. Owing to their strong interest in building democratically-owned local institutions, many co-operatives emerged in the same towns where Douglass spoke.

Not only did Douglass speak in Rochdale, the English cradle of the co-operative movement, but Douglass had also spoken earlier in Fenwick, on April 6, 1846. Fenwick is the Scottish birthplace of the Fenwick Weavers (1761-1839), an earlier model of co-operatives.

It was an era of societal change which sought democracy and abhorred slavery of any kind. The audiences that came to hear Douglass wanted to build the same slavery-free world that Douglass spoke of. The fledgling co-operative movement was an ardent activist in the British fight against slavery everywhere

While in Britain; Douglass was introduced to other efforts to obtain democratic rights. The British Chartist leader, the Irish born Feargus O’Connor, led the actions to create co-operative land societies. Members would buy shares in a land co-operative that would use the combined funds to buy land, and then by lottery, allocate parcels of the land to its members. The intent was to create a parcel of land of the value that would give the member the right to vote. Thousands of democratic activists bought shares in these Chartist Co-operative Land Companies and a number of the Rochdale Pioneers were among them.

Since Douglass spoke, on occasion, on the same platform as O’Connor during his stay in Britain, Douglass would have learned of the Chartists’ property path to democracy. Douglass also often spoke on the same platform as William Lovett and Henry Herrington, and many of these Chartists later played a role in evangelizing about working people needing to start co-operatives. There is a possibility that Douglass may have visited one of the Chartist colonies (possibly Heronsgate) to see how the parcelling of property had created a number of voting free-holders.

John Bright was the first president of the similar efforts of the Rochdale Freehold Society. In 1850, the society bought 24 acres of land in Rochdale which was then divided up into 500 plots of land for houses that would be create 500 new voters in the town. There is an area of Rochdale today still called Freehold centred on Freehold Street. Extending the vote to the middle and working classes would energize new political parties that would later change the face of British politics.

Douglass sometimes stayed at the Reform Club on Piccadilly in London as a guest of John Bright during his lengthy sojourn in Britain, (1845-47.

There is a second possibility of Frederick Douglass and Charles Howarth, (one of the original 28 founders of the Rochdale Pioneers and its second President) being in the same room at the same time. It is documented separately that in 1847, Douglass and Howarth were each in the House of Commons in the “Strangers Gallery” (a balcony with three narrow rows of seating for guests and visitors) to hear John Bright speak on the Ten Hours Bill. What has not been possible to confirm is whether it was on the same date.

2. Chronology of Support for the US North in the Civil War (1861-65):

The Role of Douglass, Bright, Rochdale, and Co-operatives

- Frederick Douglass had a long and strong friendship with John Brown that began in Brown’s home in Springfield, MA, in 1847. In 1858, Brown stayed with Douglass at his home in Rochester, NY, and asked Douglass to take part in the attack at Harpers Ferry. In August of 1859, Douglass met secretly with Brown at a quarry near Chambersburg, PA, to discuss the details of the raid. At that meeting, Douglass told Brown he would not participate.

- Douglass was giving a talk when he heard that the Harper’s Ferry Raid had begun. Douglass immediately fled to England in fear of being arrested as a John Brown accomplice. Douglass arrived in Liverpool on November 24, 1859, and spent Christmas and January with Julia Crofts (née Griffiths) and stayed in Britain (leaving from Liverpool on April l, 1860) until he was assured that his relationship to Brown was no longer cause for his arrest. (Frederick Douglass Encyclopedia, p. 60).

- When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the bottom fell out of the cotton market at the Manchester Exchange. Soon hundreds of cotton manufacturers in Lancashire either closed down or substantially reduced production. Sixty percent of the mills were idle. Thousands of cotton factory workers were laid off and they and their families faced new levels of poverty and starvation.

- During the 1860s, the Rochdale Observer newspaper actively opposed slavery. The paper printed numerous letters from Rochdale millworkers who had immigrated to the USA to escape the unemployment caused by the Civil War. Those letters urged the people of Rochdale to keep up their support by describing the slavery they had seen and learned about in the USA. The Rochdale and other British cooperators who had arrived in the USA immediately organized consumer co-ops in the mill towns of the US North East. A co-op in the town of Lawrence, MA, is a good example of the activist impact of millworker immigrants from Rochdale. The American co-ops started by British immigrants from the mill towns of the US Northeast also took strong action against slavery.

- In 1863, to honor the efforts of those Americans who fought against slavery and supported the North against the South during the Civil War, the Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS) in Manchester adopted their motto as “Labor and Wait” spelling Labor in the American style. In addition, the CWS leaders renamed their annual meeting their “Congress” and the chairman of “Congress” was renamed President. Over 160 years later, the annual meeting of British co-ops is still called “Congress” in honor of those who fought slavery.

- Lincoln kept a framed photo of John Bright in his office in the White House. It was the only photo on display.

- After Lincoln was shot, historians looked at what was in his pockets. One item they found there was a clipping of John Bright urging people to vote for Lincoln.

- In Britain, Manchester was the heart of the fight against the South and slavery and the Union and Emancipation Society was the leading voice and critical organizer of British anti-slavery opinion during the US Civil War. The largest indoor-attended anti-slavery meetings in Britain were held at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. Douglass had spoken eight times at the Free Trade Hall and other Manchester locations in 1846 and 1847, and once in 1860.

- J. C. Edwards and E. O. Greening were the hard-working, unpaid “Honorable Secretaries” of the Union and Emancipation Society, Britain’s most powerful organization against slavery and in favor of the North. Edwards and Greening were also both elected board members and officers of the Co-operative Wholesale Society. Thomas Bayley Potter, the Chairman of the Union and Emancipation Society, was Member of Parliament for Rochdale from 1865-1895. In 1891, his niece, Beatrice Potter, wrote “The Co-operative Movement in Britain.”

- There is a statue of Abraham Lincoln in Manchester – one of only a few in Britain. On the plinth is Lincoln’s personal letter of January 13, 1863, addressed to “The Workingmen of Manchester.”

- The Touchstones Museum in Rochdale has the only remaining barrel of those 15,000 barrels of flour sent to Liverpool in 1863, on the SS Griswold. The barrels of flour were sent by sympathetic Americans to feed people in Lancashire hungry from the vast unemployment caused by the Cotton Famine.

- During the Cotton Famine, The Rochdale co-op used its meeting and reading rooms for classes to increase the educational capacity of the members who were unemployed.

- In late 1862, along with other Northern towns, thousands of inhabitants of Rochdale personally signed a petition asking Lincoln to free all slaves in the USA. That petition is in the collection of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. Hundreds of co-op members from Rochdale will have signed the petition. By 1865, there were 5,326 members of the Rochdale co-op.

- When the Rochdale Pioneers opened their new main store on September 28, 1867, they invited English-born Richard Hinton to speak at the ceremony. Hinton was an avid enemy of slavery and a close friend and associate of John Brown. Hinton had reached the rank of Colonel in command of Colored Regiments and was also Acting Inspector General of the Freedman’s Bureau during the Civil War.In Alfred Square, Manchester in front of Manchester’s City Hall are two large statues of Abel Heywood and John Bright. They are both prominently placed equidistant from the Albert Memorial centerpiece. Both of these reformist leaders spoke out vociferously against slavery and both of them urged working people to join co-operatives.In 1863, 300 Lancashire and Yorkshire co-operatives banded together to form the North of England Co-operative Society. In 1872, that society changed its name to the Co-operative Wholesale Society and in 2001, the name was changed again to its present-day name, The Co-operative Group. No matter the name, from 1863 forward to this very day, Manchester has been the commercial and administrative center of the British Co-operative Movement.

- Co-operatives have always been linked with efforts to build a better and inclusive world. The ties started in 1846, between Frederick Douglass, John Bright, Rochdale, and Co-operatives, paved the way for a very special road. Cooperators today continue that work in Britain, the USA, and all around the world. What a great start we were given.© David J Thompson 2022