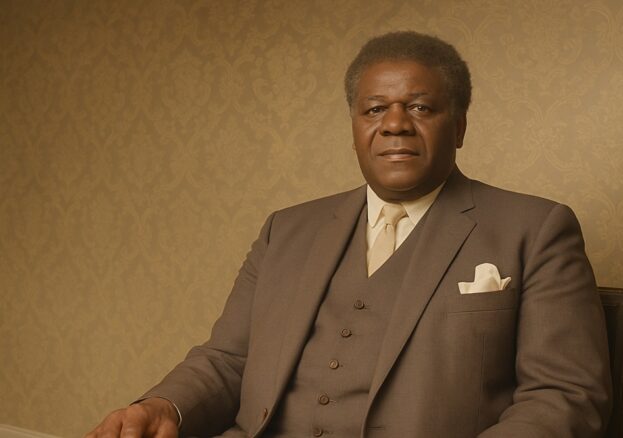

David Thomas Pitt, later Baron Pitt of Hampstead, stands as one of the most significant Black political figures in twentieth-century Britain. His life’s work combined the care of a doctor with the conviction of a campaigner and the resolve of a politician. Across medicine, local government, anti-racist organising, and the House of Lords, he sought to address the inequalities that scarred British society. Pitt’s story is also a lens onto the challenges faced by Britain’s Caribbean migrants and their descendants: the struggle for recognition, the persistence of prejudice, and the determination to claim space in public life.

Born in 1913 in the parish of St David’s, Grenada, Pitt’s academic promise was evident early. The Island Scholarship he won in 1932 gave him the chance to study in Britain, at the University of Edinburgh. There he trained as a physician, graduating in 1938 with honours. The Edinburgh years were transformative. The Depression had laid bare the links between poverty and health; Pitt immersed himself in socialist circles and began to see medicine not simply as clinical care but as a tool for social justice. His encounters with racism—at times casual, at times overt—were jarring but also clarifying, teaching him that the prejudice experienced by colonial students was part of a wider structure of exclusion that would have to be challenged politically as well as professionally.

Born in 1913 in the parish of St David’s, Grenada, Pitt’s academic promise was evident early. The Island Scholarship he won in 1932 gave him the chance to study in Britain, at the University of Edinburgh. There he trained as a physician, graduating in 1938 with honours. The Edinburgh years were transformative. The Depression had laid bare the links between poverty and health; Pitt immersed himself in socialist circles and began to see medicine not simply as clinical care but as a tool for social justice. His encounters with racism—at times casual, at times overt—were jarring but also clarifying, teaching him that the prejudice experienced by colonial students was part of a wider structure of exclusion that would have to be challenged politically as well as professionally.

After qualifying he returned to the Caribbean, practising first in St Vincent and then in Trinidad. In San Fernando he opened a general practice and entered local politics, joining the West Indian National Party and advocating greater self-government. These years reflected the dual commitments that would shape his life: the doctor’s vocation to treat individuals in need, and the activist’s duty to confront systemic injustice. Yet the pull of Britain was strong. In 1947 he returned permanently, settling in London just as the post-war migration from the Caribbean was beginning.

Doctor and Community Leader in London

In London he established a surgery near Euston. His patients were drawn from the growing community of Black and Asian migrants who often faced poor housing, insecure work and discrimination in access to services. For many, Dr Pitt was more than a physician; his practice became a community hub where people sought guidance about employment rights, landlords, or local politics. It was here that his conviction deepened that health outcomes could not be separated from social conditions, and that fighting ill-health meant confronting poverty, racism and inequality.

Politics offered a route to do just that. Pitt joined the Labour Party and quickly became active in local affairs. In 1959, a decade after the arrival of the Empire Windrush, Labour selected him to contest Hampstead in the general election. It was a landmark: the first time a major British party had adopted a Black candidate for Parliament. The reaction, however, revealed the virulence of racism in late-1950s Britain. Pitt and his family received death threats; far-right organisations mobilised against him; the atmosphere of hostility was such that his chances of victory were slim. Yet his candidacy itself marked a breakthrough. By standing, he challenged the unspoken assumption that Parliament was the preserve of white Britons. His defeat did not diminish the symbolic importance of the campaign. Eleven years later he contested Clapham, facing similar abuse, and again lost. But by then the precedent had been set: Black Britons would continue to press their claim to representation in Westminster until it was achieved.

Pitt’s influence was also felt in local government. He was elected to the London County Council in 1961, representing Stoke Newington and Hackney North, and from 1964 sat on the Greater London Council (GLC). In 1974 he became the first Black chair of the GLC. From these positions, he championed housing reform, educational opportunities and access to public services. Long before “health inequalities” became a recognised policy concern, Pitt was linking poor housing, unemployment and discrimination to patterns of ill-health in London’s working-class communities. His politics fused professional insight with civic responsibility.

Politics, CARD, and the Struggle for Equality

The mid-1960s were a turning point in Britain’s response to racism. Inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to London in 1964, Pitt helped to found and then chaired the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD). CARD brought together immigrant associations and anti-racist groups to press for legal protection against discrimination. It lobbied Parliament, built coalitions, and contributed to the momentum that resulted in the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968. Though CARD was short-lived—wracked by ideological divisions and the difficulty of sustaining grassroots organisation—its significance was considerable. For the first time, Britain had a national, organised campaign demanding statutory equality, and Pitt was at its helm. His ability to combine the respectability of a doctor and a councillor with the urgency of anti-racist activism gave CARD credibility with both policymakers and campaigners.

Recognition came in 1975 when he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Pitt of Hampstead. He was one of the earliest Black life peers, following Learie Constantine in 1969. In the Lords, Pitt spoke with authority on housing, healthcare, education and immigration. During debates on the Race Relations Act 1976, he pressed for stronger provisions and warned that without genuine equality Britain risked social division. He challenged restrictive immigration measures and urged integration through fairness rather than exclusion. His contributions were informed by decades of medical practice and community engagement, grounding parliamentary debate in lived reality.

Pitt’s commitments extended beyond race relations. He was a consistent advocate for the National Health Service and for preventive healthcare. His presidency of the British Medical Association in 1985–86 crowned his medical career and symbolised the respect he had earned in his profession. To him, medicine and politics were never separate domains; both were instruments to advance human dignity.

In the House of Lords and Beyond

His surgery in North Gower Street, meanwhile, doubled as a site of solidarity with the global anti-apartheid movement. For Pitt, the struggles against injustice in Britain and in South Africa were connected. He encouraged young Black Britons to enter the police and other public services, believing that representation inside institutions was essential for change. Some activists criticised this stance as too conciliatory, but for Pitt it was part of a consistent strategy: reform institutions from within while pressing them from without.

David Pitt died in London on 18 December 1994, aged 81. His death was marked by tributes from across medicine, politics and community life. His legacy is both practical and symbolic. Practically, he helped build the architecture of anti-racist reform: campaigns, committees, legislation, and public offices that pushed Britain from informal tolerance towards statutory equality. Symbolically, his presence in elections, councils, and the Lords demonstrated that Black Britons had both the right and the capacity to shape the nation’s political life.

Legacy

Pitt’s legacy is twofold. First is the practical architecture of equality—the committees, campaigns, and debates through which he turned moral claims into policy proposals and then into law. From CARD to the Race Relations Acts, he worked to embed fairness within Britain’s institutions. Second is the symbolic and cultural dimension of representation. By standing in 1959, he demonstrated that a Black professional could seek a mandate in a national election; by entering the Lords in 1975, he took a seat at the centre of legislative authority. Importantly, Pitt insisted that representation be judged by outcomes: better housing, equal access to services, and an end to discriminatory practices. For Black History Month, his life is a reminder that standing firm is not only a posture; it is also a programme—sustained, sometimes unglamorous, and oriented to the public good.

References and Further Reading

Core references

- UK Parliament / Wikipedia. David Pitt, Baron Pitt of Hampstead (biography, elections, peerage).

- University of Edinburgh, UncoverED Project. “David Pitt” (student years, CARD involvement).

- Parliamentary Archives Blog. “The Noble David Pitt: From Grenada to Camden.”

- The Independent. “Obituary: Lord Pitt of Hampstead,” 19 December 1994.

- The New Yorker. “Color in the Mother Country,” 1965 (contemporary coverage of CARD).

Further reading

- Mike Phillips, “Pitt, David Thomas, Baron Pitt of Hampstead,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- David Olusoga. Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016).

- Kalbir Shukra. The Changing Pattern of Black Politics in Britain (1998).

- James Walvin. Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016).

- Muhammad Anwar. Race and Politics: Ethnic Minorities and the British Political System (1986).

- Trevor Phillips & Mike Phillips. Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain (1998).