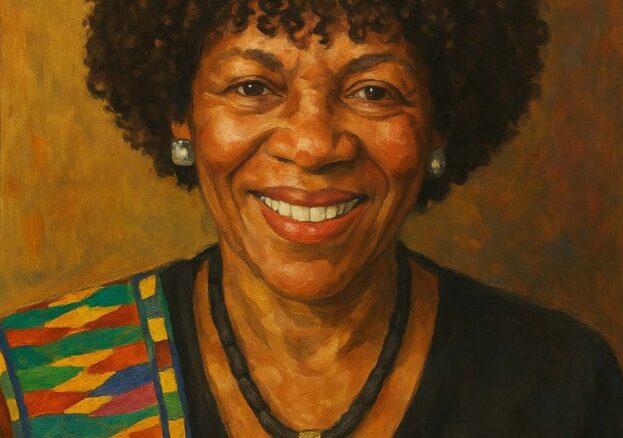

Margaret Busby has spent her life opening doors. As a young woman in the 1960s, she broke into the closed world of British publishing and became the country’s first Black female publisher. As a writer, editor, broadcaster, and cultural activist, she has consistently championed voices that had been ignored or marginalised. For more than half a century, she has reshaped not only what we read, but how we think about literature itself.

She was born in 1944 in Accra, Ghana, into a family that believed education and creativity could change lives. Her father, Dr George Busby, was a respected physician and public health advocate, and her mother, Mrs Sarah Busby, nurtured her children’s curiosity. At the age of six, Margaret was sent to school in Britain, part of a generation of African children educated in the “mother country.” She later studied English at Bedford College, University of London. It was there, in her early twenties, that she met Clive Allison, with whom she would launch a venture that would alter the landscape of British publishing.

In 1967, Allison & Busby was founded. Two outsiders — one a young Ghanaian woman, the other a radical white Englishman — set up a company in a field dominated by conservative, middle-class men. The odds were against them. But what they lacked in capital and experience, they made up for in vision and determination. Their mission was simple yet daring: to publish books that were bold, inclusive, and unafraid of challenging convention.

The list they built was extraordinary. Allison & Busby championed writers who might otherwise have been excluded from the British literary establishment. They published the radical African American novelist Sam Greenlee (The Spook Who Sat by the Door), the trailblazing Nigerian-British author Buchi Emecheta, Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah, Trinidadian writer C. L. R. James, and American YA pioneer Rosa Guy. They also produced politically engaged works, biographies of jazz musicians, and countercultural texts that reflected the ferment of the times. Their books were striking not only for their content but for their design: Allison & Busby titles looked and felt different, accessible to young, diverse, and politically conscious readers.

For Margaret Busby, this was not just publishing — it was activism. She believed in literature as a tool of visibility and liberation. By the 1970s, she had become a rare presence in an industry that too often saw Black voices as “niche.” She insisted that British literature must reflect the full richness of its society and its global connections. Her approach anticipated debates that are still playing out today.

After leaving Allison & Busby in the 1980s, Busby continued to shape culture through many roles. She wrote plays for theatre and radio, including Yaa Asantewaa – Warrior Queen, which brought African history into the spotlight. She worked as a broadcaster, presenting programmes on the BBC that introduced audiences to new voices and ideas. As a literary critic, she lent her authority to debates on diversity, equality, and the arts. And as an editor, she undertook a project that would become one of her defining achievements.

In 1992, Busby published Daughters of Africa, an anthology that brought together the work of more than 200 women writers of African descent. From poets and novelists to essayists and storytellers, the book created a lineage of creativity stretching across continents and centuries. It was an act of both scholarship and celebration, mapping a tradition that had too often been overlooked. Nearly three decades later, she returned to the idea with New Daughters of Africa (2019), featuring over 200 more writers, from household names like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Zadie Smith to emerging voices. Both volumes have become landmarks, ensuring that the contributions of African women to literature cannot be erased.

Busby’s influence has also been felt through her work with prizes and institutions. She has served as a judge for countless awards and in 2020 became the first Black woman to chair the Booker Prize panel. Her commitment to mentoring younger writers and editors has nurtured a new generation of literary talent. She has been recognised with numerous honours: she was appointed OBE in 2006 and advanced to CBE in 2021, has received multiple honorary doctorates, and was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2017.

And yet, Busby remains characteristically modest. She often describes herself simply as someone who loves books and wants to share them. Her activism is rooted in joy as much as in justice — in the belief that reading is not just an intellectual act, but a deeply human one that connects us across borders and histories.

For Black History Month, her story holds particular resonance. Margaret Busby reminds us that representation is not a trend, but a necessity. Without diverse publishers, many of the voices that shape today’s culture might never have reached readers. Without editors like her, the canon itself would look smaller, narrower, less true. She has proved that publishing is not just an industry but a cultural act with political consequences.

More than half a century after she began, Margaret Busby is still a force in British letters. She remains a sought-after speaker, an advisor to institutions, and a tireless advocate for inclusivity. She has shown that one person with conviction can alter the shape of an entire industry. And she has ensured that the daughters of Africa — past, present, and future — will always have their voices heard.

Further Reading & Sources

- Margaret Busby (ed.), Daughters of Africa (1992)

- Margaret Busby (ed.), New Daughters of Africa (2019)

- Interviews with Margaret Busby in The Guardian and The Independent

- British Library, “Margaret Busby: Publisher and Cultural Activist”

- Booker Prize Foundation archives (2020, chaired by Busby)

- Royal Society of Literature: Honorary Fellows