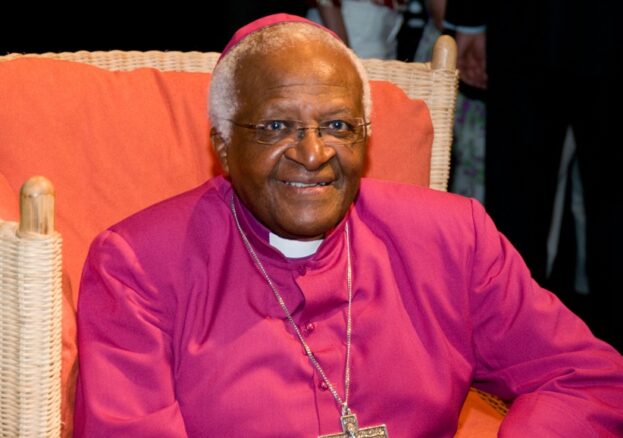

It is almost impossible to conjure Desmond Tutu without hearing his laugh. High-pitched, childlike, utterly infectious, it would bubble out of him at the most unexpected moments. He laughed in meetings with heads of state, he laughed in the corridors of power, he laughed even when recounting some of the darkest days of his country’s torment. For many, it seemed almost incongruous that a man carrying so much pain should be so full of joy. But in truth, his laughter was one of his greatest weapons. It was a sound of defiance, a refusal to surrender his humanity to an inhuman system. Under the long, bleak night of apartheid, when brutality was policy and cruelty the law of the land, Desmond Tutu’s laughter was rebellion. It was the declaration that dignity, once rooted, cannot be crushed.

Born in 1931 in Klerksdorp, a dusty mining town in South Africa’s Transvaal, Desmond Mpilo Tutu’s early life gave no sign of the international figure he would become. His father was a teacher, his mother a domestic worker. His family lived modestly, part of the precarious Black middle class that apartheid would soon squeeze and humiliate. As a child he suffered from polio and tuberculosis, spending long months in hospital. He survived, but the experience left him with deep empathy for the suffering of others. He had planned to follow his father into teaching, and indeed qualified in the early 1950s. But when the apartheid government introduced the notorious Bantu Education Act in 1953, deliberately designed to keep Black South Africans uneducated and servile, Tutu resigned in disgust. He could not in good conscience participate in a system built to break the minds of children.

It was then that he turned to the Church. The Anglican communion offered him a different kind of pulpit, one from which he could speak truth to power with authority and protection. He was ordained in 1961 and proved immediately that he was not simply a parish priest. His sermons combined the thunder of a prophet with the tenderness of a pastor. He could denounce apartheid as “evil, unchristian and immoral,” and in the next breath remind his listeners that they were loved, cherished, precious. His Christianity was no quietist creed of resignation; it was a faith of fire, rooted in justice, rooted in the God who stood with the oppressed.

His rise was rapid. Dean of Johannesburg. Bishop of Lesotho. Then, in 1975, the first Black Dean of St Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg, a position long reserved for whites. The timing was fateful. In 1976, schoolchildren in Soweto rose up against the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. The police fired live ammunition, killing hundreds. The uprising spread like wildfire across South Africa. And into this storm walked Tutu, newly appointed Bishop of Johannesburg. He was no armchair cleric. He was in the streets, comforting parents, shielding children, confronting police. He became, in that moment, not simply a bishop but a national conscience.

In 1978 he was appointed General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches. From this platform his voice reached the entire nation. He framed the struggle not in the language of Marxism, which the regime dismissed as foreign, but in the language of morality, which it could not so easily ignore. He declared apartheid blasphemy, heresy, a sin against God and humanity. The government loathed him. He was denounced, threatened, vilified in the press. His passport was confiscated. He was regularly harassed by the police. Yet he refused to be silenced.

By the 1980s, Desmond Tutu had become the most recognisable face of resistance within South Africa. With Mandela silenced behind bars on Robben Island, it was Tutu who carried the flame of the movement to the outside world. He travelled tirelessly, urging sanctions, speaking at universities and parliaments, pressing foreign governments to cut ties with the apartheid regime. In Britain, he clashed directly with Margaret Thatcher, who insisted on “constructive engagement.” Tutu’s reply was devastatingly simple: “The system is killing people already. Sanctions are the price we pay for freedom.” His words carried the moral clarity of a prophet, and he would not blunt them to please the powerful.

The world took notice. In 1984 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel Committee hailed him as “a unifying leader figure in the campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid.” The award not only honoured him but offered him protection. The regime could no longer move against him without provoking international outrage. He used that space to intensify his advocacy, lending his small frame and booming laugh to marches, funerals, rallies, sermons. He became the living embodiment of nonviolent resistance.

And yet for all his seriousness, he remained irrepressibly joyful. Journalists were often startled when, after excoriating the apartheid system as demonic, he would break into peals of laughter at some absurdity. His laughter was not escapism; it was strength. It was his way of refusing to let hatred dictate the terms of his life.

When Mandela was finally released in 1990 and South Africa began its halting transition to democracy, Tutu was once again at the centre. Mandela called him “the voice of the voiceless.” In 1994, when the first free elections were held, Tutu coined the term “the Rainbow Nation,” capturing the fragile hope that South Africa might transcend race and build unity out of diversity. President Mandela asked him to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It was an extraordinary experiment: instead of revenge, there would be truth; instead of silence, testimony; instead of impunity, confession. Tutu sat at the hearings day after day, listening to victims describe atrocities, listening to perpetrators admit crimes. He wept often, covering his face with his hands, his body shaking with sobs. But he insisted it was necessary: “Without forgiveness,” he said, “there is no future.”

His life, though rooted in South Africa, was deeply intertwined with Britain. He had first arrived in London in 1962 to study theology at King’s College. Those years abroad broadened his perspective, exposing him to the complexities of empire, race and faith beyond his homeland. He formed friendships that lasted a lifetime. Britain became not just a place of study but a second home of sorts. He returned frequently, especially in the 1980s, urging the British government to take a harder line against apartheid. For many in Britain’s Black communities — in Brixton, Toxteth, Tottenham — he became a symbol that faith and fire could walk hand in hand.

In 1990, only months after Mandela’s release, he came to south-east London to receive the Freedom of Lewisham, honoured at Goldsmiths. In Hull, he was awarded the Freedom of the City and later the Wilberforce Medal, linking his struggle to Britain’s own abolitionist heritage. In 1994 he delivered a sermon in Britain marking South Africa’s re-entry to the Commonwealth, a symbolic return to the family of nations. And in November 2013, in one of the most poignant encounters of his later life, he was received by Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace. The Archbishop, beaming as always, stood before the monarch whose empire had once ruled his land. The photograph of their meeting captured a moment of history: the laughing prophet and the long-reigning queen, bound together by the weight of a shared past and the hope of a reconciled future.

But Tutu never allowed himself to become a mere symbol. Even in his later years he was fearless in speaking truth. He condemned homophobia with the same passion he had condemned racism, declaring: “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. I would not worship a God who is homophobic.” He criticised the Iraq War, warned against the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories, and lambasted corruption and betrayal within post-apartheid South Africa itself. He loved the Rainbow Nation, but he would not flatter its leaders when they fell short.

His words could sting, but they were never without hope. “Hope,” he said, “is being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness.” And again: “Do your little bit of good where you are; it’s those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.”

Desmond Tutu died on 26 December 2021, aged 90. True to his humility, his coffin was plain, his funeral modest. No grand display, no pomp. Just the final act of a man who believed that greatness lies not in spectacle but in service. South Africa mourned, Britain remembered, the world gave thanks.

What remains is not only his record of resistance, but his model of humanity. He showed that justice can be fierce and still full of joy. He showed that forgiveness is not weakness but strength. He showed that laughter can be a weapon sharper than any sword. From Klerksdorp to Soweto, from King’s College London to Buckingham Palace, his life was a bridge between continents and consciences. He was a prophet, a priest, a politician of the spirit. Above all, he was a human being who never let go of his humanity, even in a world designed to strip it away.

Further Reading & References

Books

- Desmond Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness (1999)

- Desmond Tutu, God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time (2004)

- John Allen, Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorised Biography of Desmond Tutu (2006)

- Desmond & Mpho Tutu, The Book of Forgiving (2014)

Online Resources

- Nobel Prize biography

- BBC News obituary

- South African History Online

- University of Oxford Alumni Profile

- Africans in Yorkshire Project