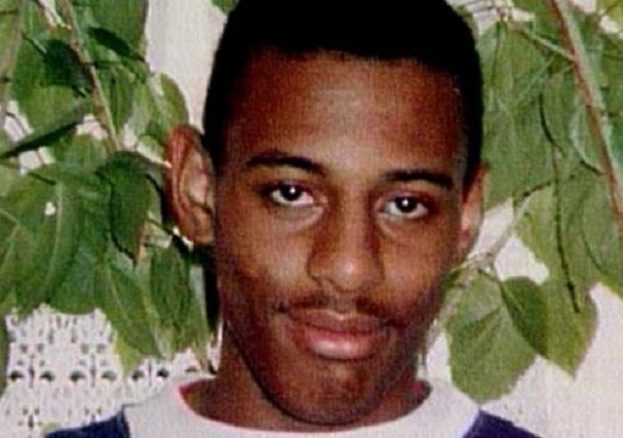

It is 20 years since the publication of the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report. Barbara Cohen discrimination lawyer and a former Runnymede Trustee traces what became the laws and policies the Report inspired and the aspirations and expectations the Report created.

The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry by Sir William Macpherson and his advisers held 69 days of public hearings, heard 88 witnesses and considered thousands of pages of evidence. Media coverage throughout meant that the facts examined by the Inquiry were well known. So, when the Report stated the Inquiry’s finding that ‘institutional racism played a part in the failed police investigation’ and that it existed not only in the police but in ‘other institutions countrywide’ , their words reverberated everywhere.

There were banner headlines across the political spectrum: ‘Watershed for a fairer Britain’ (Evening Standard); ‘An historic race relations revolution’ (Daily Mail)’; ‘Dossier of shame that will change the face of Britain’s race relations’ (Daily Mirror); ‘Racists won’t win’ (Sun); ‘Never ever again’ (Express); ‘Findings should open all our eyes’ (Daily Telegraph).

Key findings and recommendations

- There needs to be a renewed focus on institutions as recommended in the Lawrence Inquiry report. This includes the police, but also all public, private and charitable institutions, who must continuously guard against policies and practices that would deny fair treatment and outcomes for Britain’s 8 million black and minority ethnic (BME) people

- The legacy of the report is being undermined by the failure of successive governments, especially since 2010, to give full effect to the ‘public sector equality duty’. Had the duty been working as intended, the worst of the Windrush injustices should not have occurred.

- Other recommendations of the Lawrence Inquiry report still need attention, including representation in the police. An often overlooked recommendation is on the need for more accurate teaching of Britain’s diverse history and our place in the world.

A blunt analysis: institutional racism

On this 20th anniversary it is impossible not to be struck by the honesty and courage of the Inquiry panel, who did not take the obvious course and attribute the failed police investigation to incompetence, or incompetence combined with the racism of a few ‘bad apples’ within the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS). They did not rely on the ‘disadvantage’ of the black community, but asserted that ‘Mere incompetence cannot of itself account for the whole catalogue of failures, mistakes, misjudgements, and lack of direction and control which bedevilled the Stephen Lawrence investigation’ . The conclusion that ‘pernicious and persistent institutional racism’ – so well embedded that no one within the MPS ever questioned how it operated – played a part was ‘fully justified’

They defined institutional racism as: “the collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people”.

Identifying the problem is only the first stage. ‘There must be an unequivocal acceptance of the problem of institutional racism before it can be addressed, as it needs to be, in full partnership with minority ethnic communities’. ‘It is incumbent on every institution to examine their policies and the outcome of their policies and practices to guard against disadvantaging any section of our communities’ .

The concept of institutional racism was not new; it had been developed over several decades by activists and academics in the US and Britain who had given a name to the phenomenon that was part of black people’s routine encounters with public and private organisations.

The Report stressed that finding institutional racism in the operations of the MPS did not mean they found MPS policies to be racist or every officer guilty of racism. Nevertheless, it took some time for the MPS Commissioner and other chief constables to accept the need for institutional change. The Home Secretary immediately accepted the finding of institutional racism; the day after the Report was published, he announced plans to implement most of the 70 recommendations, including to bring the police and all public authorities fully within the scope of the Race Relations Act 1976 (RRA).

From Macpherson to the Race Relations (Amendment) Act

These were exciting times. Change was going to happen. Race equality non-governmental organisations convened by the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) agreed to campaign for new legislation, to include a race equality duty on public bodies.

By December 1999, the government had introduced a bill to amend the RRA to prohibit direct race discrimination by all public authorities, omitting indirect discrimination – often the consequence of institutional racism. Following months of strenuous lobbying, at the final stage Parliament approved the bill prohibiting both direct and indirect race discrimination by all public authorities and imposing on public authorities a statutory race equality duty. This amended RRA was immediately seen as a ground-breaking equality law, not only for Britain but internationally.

The amended RRA s. 71 provided that every specified or defined public authority ‘shall, in carrying out its functions have due regard to the need – a) to eliminate unlawful racial discrimination; and b) to promote equality of opportunity and good relations between persons of different racial groups.’

In October 2001, an order by the Home Secretary imposed ‘specific duties’ on public authorities to ensure ‘the better performance’ of their duty. A central requirement was to publish a race equality scheme showing how the authority would fulfil its race equality duty by identifying which of its functions were relevant to the duty, and how it would assess and consult on race equality impact, train staff, and monitor workforce matters.

Implementing the Race Relations (Amendment) Act

When the Race Relations (Amendment) bill was going through Parliament, the CRE and Home Office officials discussed how a race equality duty could be enforced. The consensus was that the main enforcement role should be performed by those regulatory bodies already in place to monitor and enforce legal compliance by public bodies, such as the National Audit Office (NAO), OFSTED, HM inspectorates of police and prisons, and inspectors/regulators of the NHS. That such bodies never fully took on this role remains a disappointment.

The CRE issued a statutory code of practice and was given new powers to secure compliance with the specific duties. However, more effective enforcement was occurring through applications for judicial review in which the High Court was asked to determine whether, in taking particular action, a public authority had complied with its race equality duty. Court decisions provided greater clarity as to what steps a public authority needed to take to show that it had had the required ‘due regard’ to race equality.

A range of important policies were successfully challenged in this way on the grounds that the authority had failed to consider race equality implications before adopting the policy, including:

- A scheme to compensate former Japanese prisoners of war, but only those who met a UK residence test;

- A local authority policy which would have required Southall Black Sisters, an agency providing specialist advice to Asian women, to change totally its client group;

- Changes to the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme which would have effectively barred non-EU doctors from applying for first-tier doctor appointments;

- A local authority decision to cut funding to legal entitlement advice services serving ethnic minorities and others;

- An amendment of rules to extend the use of physical restraint for ‘good order and discipline’ in secure training centres, where a high proportion of young offenders are BME

It is right to give credit to the Labour Government for its prompt and positive response to the Report, with new laws and policies creating a moment in British history of the widest state commitment to exposing and combating racism. However, like previous governments which had legislated against race discrimination, it was not deterred by that commitment from enacting harsh immigration and asylum laws and antiterrorism laws. Had any of them been subject to a race equality impact assessment, possibly none of these measures would have passed, since by their nature they relied on differential treatment of members of groups primarily defined by race (nationality, ethnicity or national origins).

In 2007, under the Equality Act 2006, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) replaced the CRE, the Equal Opportunities Commission and the Disability Rights Commission and became an equality body for seven protected characteristics,12 all of which, by then, were included in UK anti-discrimination legislation. The EHRC took over all of the functions of the CRE with some added powers, and inherited some unfinished cases; otherwise, between 2007 and 2010 its main engagement with the race equality duty was to intervene in external applications for judicial review.

In 2005, the government had commissioned the Discrimination Law Review with the aim of enacting a single equality act for Great Britain. In 2007, it published its proposals for consultation, and in 2009 it introduced the Equality Bill. Broadly, the bill harmonised and restated existing laws, extended them to nine protected characteristics, and included some new provisions and a public sector equality duty (PSED) that applied to eight protected characteristics. It completed its passage on the final day of Parliament before the 2010 General Election.

The dilution of race equality protection since 2010

A first task of the new Coalition Government was to complete the legal framework for the PSED in the new Equality Act 2010. Its stated aim for introducing the PSED was:

- To build on and simplify the previous duties and to extend the duty to other protected characteristics;

- To be outcome focused;

- To reduce the bureaucracy associated with the previous duties.

It sought to achieve this by imposing two specific duties on national and non-devolved public bodies,15 namely: a) to publish annually information demonstrating its compliance with the PSED; b) to prepare and publish at least every four years one or more specific, measurable objectives to meet

Compared to the specific duties under the previous race, disability and gender equality legislation, this significantly slimmer set was read by most public authorities as an intentional downgrading of the importance of the PSED. Many were relieved that at a time of major budget cuts, equality was something they no longer needed to prioritise. Between 2011 and 2017, the EHRC did not once use its statutory powers to enforce PSED compliance.

In April 2011, the Coalition Government launched its Red Tape Challenge, by which, with public consultation, they would repeal the acts, orders and regulations which they concluded were unduly burdensome. For three weeks in June 2011, the Red Tape Challenge spotlight was on equalities – the Equality Acts 2006 and 2010. This resulted in the repeal of provisions of the 2010 Act, making it more difficult to bring discrimination claims, the repeal of certain EHRC functions, and the reduction of the EHRC’s budget and independence. A review of the PSED followed during 2012–13; it was mainly inconclusive – recommending a thorough review in 2016, but also a ‘more proportionate’ approach to compliance by public authorities.

Speaking to the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) in November 2012, the Prime Minister emphasised his Government’s position:

“Take the Equality Act. It’s not a bad piece of legislation. But in government we have taken the letter of this law and gone way beyond it … I care about making sure that government policy never marginalises or discriminates … [that] we treat people equally. But … caring about these things does not have to mean churning out reams of bureaucratic nonsense … We don’t need all this extra tick-box stuff. So … today we are calling time on Equality Impact Assessments. You no longer have to do them if these issues have been properly considered”.

Policies that avoided the PSED: Counterterrorism, immigration and criminal justice

In 2015, when public bodies were feeling less pressure to comply with the PSED, they were given a new duty under the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 which had the same format and weight as the PSED: a duty ‘in the exercise of its functions’ to ‘have due regard to the need to’ in this case ‘prevent people from being drawn into terrorism’. There is little evidence that the PSED was considered when this ‘Prevent duty’ was proposed. The Government emphasised its urgency and, unlike in the PSED, Parliament gave the Home Secretary powers to enforce compliance with Prevent through the courts. As a result, most authorities were incentivised to implement the Prevent duty with scant regard to the PSED, even when confronted with hard evidence of differential treatment based on race and/or religion.

The ‘hostile environment’ is a Home Office policy adopted in 2012 intended to deter people from coming to the UK, and to stop those who do come from overstaying. Theresa May, as Home Secretary, announced:

“The aim is to create a really ‘hostile environment’ for illegal migrants … What we don’t want is a situation where people think that they can come here and overstay because they’re able to access everything they need”.

A main feature of the ‘hostile environment’ is the major role in immigration control assigned to people other than

immigration officers. Employers, landlords, bank staff, NHS staff and other public sector workers, without appropriate training, now carry out immigration checks on the basis of which they can deny jobs, housing, healthcare and other services to undocumented migrants.

The Home Office acknowledges that it is bound by the PSED with regard to its ‘hostile environment’ policies but appears satisfied that it is compliant.18 Its only direct anti-discrimination action has been the codes of practice on avoiding discrimination which it has published for landlords and employers. It has not taken specific steps to prevent race being used as a proxy for suspect immigration status by the other agencies required to sustain the ‘hostile environment’; this includes the police (with years of evidence of disproportionate actions against BME people), who are designated to enforce conduct made criminal when carried out by a person not lawfully in the UK.

The Windrush scandal has shown that the ‘hostile environment’ is more than the sum of its parts. It was not only that it caused incredible suffering for undocumented Windrush people, but also that the government, so assured that the policy was right, could opt not to see or hear the warnings about it and the reality of its impact on the Windrush generation. Discrimination can occur in failing to act as well as in taking particular action. Referring to the Macpherson definition of institutional racism, is that not what the ‘hostile environment’ has been for the Windrush people? There was no clear intention to apply differential treatment because they are black: what the government did was to allow to continue, with enhanced severity, without scrutiny or monitoring, a scheme of linked exclusions which caused suffering to a group of black people of Caribbean origin to a disproportionate extent.

The EHRC, in its 74-page review of race inequality in Britain, mentioned institutional racism only in two quotes from external sources.

David Lammy, MP, in his 2017 Review, found that BME individuals were disproportionately over-represented in most parts of the criminal justice system and subjected to disadvantageous differential treatment. Although he was examining a range of public bodies, the PSED was mentioned only twice, and there was no mention of institutional racism but frequent reference to ‘bias’. He concludes, somewhat cautiously, that ‘BAME individuals still face bias, including overt discrimination, in parts of the justice system’ However, he says his focus was ‘primarily on the treatment and outcomes of BAME individuals rather than decoding the intentions behind countless decisions in a range of different institutions’, and to achieve ‘fair treatment’ his prescription is ‘to subject decision-making to scrutiny’.

While Lammy was concerned with the role of public policy, the Guardian, in its series of articles in December 2018, would have been more concerned with exposing hidden facts. It commissioned a survey of the ‘everyday experiences’ of people of different ethnicities and reported that regardless of the activity – employment, housing, shopping, eating out, education, driving tests, health or mental health care, police stops – ethnic minority experiences were worse than those of white counterparts. This was newsworthy because it disclosed how little had changed over decades since race discrimination was made unlawful; it was also news because of the emphasis given to unconscious bias (‘quick decisions conditioned by our backgrounds, cultural environment and experiences’) as the key factor. Over several days, the paper featured negative experiences of BME survey respondents which the journalists attributed to unconscious bias. A careful reading of the text and graphics is necessary to distinguish negative treatment which is personal in origin – such as someone at work treating me differently because of my appearance – from negative treatment which is the experience of BME people as a result of, institutional practices, such as more frequent stops by police or airport security.

Conclusion: a need to refocus on institutions

Twenty years ago, the Report said to those at the top of every organisation that they must accept the problem of institutional racism and examine the outcomes of their policies and practices to avoid race inequality. Then, for some, the language, and hence the thinking, moved from discrimination and equality to ‘diversity’, which can involve doing more but without sanction for doing nothing. Today we see many people almost automatically attributing the problem of less-favourable treatment to unconscious bias, which totally alters the dimension – no longer institutional, but primarily personal – and the responsibilities and mechanisms for change. Training to help people recognise and manage their unconscious biases is flourishing. However, there are too many examples today of BME people facing unjustifiable barriers to equality across critical areas of their lives – housing, healthcare, education, employment: the ‘treatment and outcomes’ that Macpherson described. Some people’s unconscious biases may play a part in this, but more urgently the institutions concerned need ‘to examine their policies and the outcomes of their policies and practices’ and make whatever changes are needed to provide appropriate services to all members of the community.

Is it not a sad finale to this anniversary of a Report expected to change permanently the shape of race relations in Britain that patterns of race discrimination have altered very little, while the essential political will to achieve meaningful, lasting change which existed in 1999 is gone, the commitments and mobilisations across the country to eradicate race discrimination have radically declined, and racism and racist violence have increased? In 1999, our target was for institutional racism to be tackled by the engagement of everyone within an institution.

In contrast, to overcome the results of unconscious racial bias requires a personalised solution for each individual, which can operate against achieving coherent organisational change. If we are to properly learn the lessons of the Lawrence Inquiry Report and its legacy, we need to revert to the former approach, by focusing on the institutions that continue to reproduce racial inequalities 20 years on.

Barbara Cohen is a discrimination lawyer and a former Runnymede Trustee; she served as head of legal policy at the CRE, involved in the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry and the changes to the RRA that followed.