It was the arrival of the first contingent of this pioneering generation of immigrants that heralded the beginning of what was a unique moment in Britain’s post-war history. Whilst the African presence in Britain dates back several millennia, and whilst British cities such as Cardiff and Liverpool are long-established homes to Black people from across the world, it was not until the relatively recent post-war period that particular neighbourhoods of other English towns and cities developed what were, for a while, distinct and recognizable ‘Black communities’, complete with their own particular cultural resonances. Answering the call from ‘the Mother Country’ to fill labour vacancies, hundreds of thousands of migrants from all over the Caribbean made their way to Britain, thereby setting in train developments that have ongoing repercussions, both within and beyond the cultural arena.

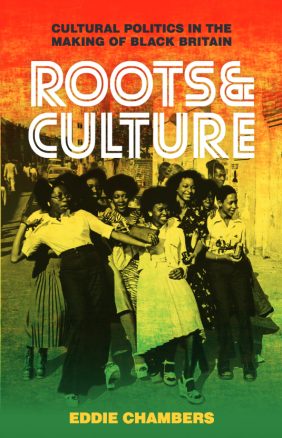

Post-war Black British history is by no means exhaustively documented and reflected on. History is not just that which happened many decades, centuries or millennia ago; history is also that which happens under our noses, during our own lifetimes, and something brought about by the actions, and thinking of ordinary people. There is much yet to be chronicled about the presence of Caribbean migrants, particularly within the arena of culture and cultural identity. It is, in so many respects, difficult to define exactly what ‘culture’ is. Dictionary definitions are not much help. The arts and other manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively is one definition, the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society being another, but when it comes to the cultural identity of Black-British people, such definitions seem to fall short. Perhaps the type of dictionary definition that comes closer to describing our cultural identity and its histories is the attitudes and behaviour characteristic of a particular social group. It is attitudes and patterns of behaviour of Caribbean migrants and their offspring that I seek to chronicle in my recent book, Roots & Culture: Cultural Identity in the Making of Black Britain. (I B Tauris & Co., 2017)

This book, as with much of my other writing, seeks to make respectful use of such things as the speech patterns and forms of communication developed by Black people. I’m of the opinion that distinct, recognisable Black talk, is altogether richer, more nuanced and far more expressive than what some regard as the Queen’s English, or BBC English. This is important because Black speech patterns are routinely marginalized or denigrated as ‘broken’, ‘faulty’, or just not ‘good English’. But the type of English that much of the wider society holds dear has failed Black people, and there are important reasons why alternative speech patterns have thrived, and continue to thrive, in the ways in which generations of Black people communicate with each other, particularly through language such as patwa. Roots & Culture asserts that patwa is nothing short of English made fit for purpose, and patwa is utilised in several of the titles of chapters of my book, such as De Street weh Dem Seh Pave Wid Gold and Leggo de Pen. Coincidentally, both of these titles are borrowed from the poetry of Frederick Williams, a ‘dub poet’ active in London in the early to mid 1980s. One of his poems bluntly opined, De street weh dem seh pave wid gold/Pave wid sou-soh daag shit (Frederick Williams, ‘A Pressure Reach Dem’, Leggo De Pen, (London: Akira Press, 1985), p. 14). The lines translate into Caribbean immigrants’ despondent realisation that ‘The streets they told us were paved with gold were actually paved with dried out dog shit’, or ‘only paved with dog shit’. Another chapter, Leggo de Pen, (which translates to Let the Pen Loose, or Set the Pen Free) is the title of a collection of poems by Frederick Williams, mentioned above. My chapter, ‘Leggo de Pen’ explores the impact of dub poetry and its extraordinary ability to articulate the fractious and disappointing aspects of Black-British experience.

Like so much street lingo, the expression ‘roots and culture’ has no straightforward translation into what might be termed ‘standard’ English. The term, popular amongst certain circles of Black-British youth in the late 1970s and 1980s and emanating from a variety of reggae tracks, came from Jamaica and meant, to be in touch with one’s roots, to have attained a certain level and type of consciousness, and to have an appreciation of the importance of Black history and culture in the construction of one’s identity. In time, roots and culture became a particular genre of reggae music, distinguished by upful and conscious lyrics of Black pride and righteousness. The term ‘roots and culture’ represents a particular period of British manifestations of Black pride, as well as African-Caribbean cultural intensity and resonance that my book seeks to historicize, drawing in, along the way, factors such as the British Empire, migration, Rastafari, the Anti-Apartheid struggle, reggae music, dub poetry, the ascendance of the West Indies cricket team and the coming of Margaret Thatcher.

My belief is that Black music (and for the purposes of my book, reggae music in particular) gives us much that articulates in the most original, pressing and cogent of terms, the experiences of Black-British people. I use song titles, or lines from songs, as titles of some of my chapters. For example, Chapter Three of Roots & Culture explores the impact of Rastafari on Black Britain, and is titled ‘Rasta This and Dreadlocks That’, a line from ‘Steppin’ Out’, a song by Steel Pulse, on their 1984 album, Earth Crisis. A later chapter, about the part that young Black British artists played in the development of a distinct cultural identity, is titled ‘Picture on the Wall’, referencing, of course, the wonderful Natural Ites song of 1983. I continue to marvel at the extent to which British reggae, as much, if not more so than its Jamaican variant, articulates and reflects in telling detail the challenges Black Britons have faced, on a number of fronts. One particularly sobering example of this is a memorable song from Aswad’s album of 1981, New Chapter, which opened with a track titled ‘African Children’. The song is a notable anthem of protest against the sort of ‘precast stonewall concrete cubicle’ living forced on those hapless residents of local council’s high rise tower blocks.

The book focusses for the most part on the cultural identity that emerged amongst Black Britons in the 1970s and early 1980, when the children of the Windrush generation came of age. It was this period that gave rise to the sorts of music and poetry that Roots & Culture so liberally draws on, and uses to frame a profound story of mutating cultural identity within a section of the African Diaspora.