Revolutionary political and musical concepts have transformed Jamaica and its relations with the outside world for centuries. From colonial times to the present day, Jamaicans have engaged in revolutionary acts of political and creative expression. In each instance, these activities have been imbued with a profound Jamaican cultural, ethnic and national pride, and made the most of dire circumstances. Jamaica’s history is filled with rebel heroes, including Queen Nanny, a runaway slave whose Maroon encampment in the Jamaican mountains was never conquered by the British colonial slavemasters, and remained an autonomous region. Her example, as well as that of slave rebellion leader Paul Bogle, human rights activist Marcus Garvey, Prime Minister Michael Manley and other political figures continually challenged the Western social and political establishment throughout the island’s development.

Jamaican music, even its celebratory dancehall and rub-a-dub forms, employs sarcasm, humor, innuendo, plays-on-words, turns-of-phrases and other literary devices to explore and expose the

good and bad in both politics and society. Contemporary Jamaican music and specifically reggae therefore has been the foundation of revolutionary movements and philosophies throughout the 20th and 21 st centuries. Jamaica as a nation has survived the eras of slavery, colonialism and finally selfrule with a proud tradition of resistance and resilience to everything from hurricanes and external economic convulsions, to gangland crime and poor infrastructure.

Against a backdrop of revolutionary socialism in the 1970s, Jamaican music equally revolutionized popular music, creating sound system culture, dublate singles and, with experimental mixing and dubbing techniques, birthed the art of remixing. Innovators such as Osbourne “King Tubby” Ruddock, Lee “Scratch Perry, Overton “Scientist” Brown, through modern producers such as Lloyd “King Jammy” James, Patrick Roberts and Dave Kelly took Jamaican music to the world via dub, reggae, dancehall and roots music. Jamaican music innovated and incorporated other genres without ever compromising its distinct cultural identity.

Today Jamaican music continues to impact everything from Latin reggaeton, to American hip-hop, and reverberates through British genres such as dubstep. Meanwhile, Jamaica’s challenge to the social and political status quo is at a crossroads, caught between its national debt and IMF policies, and the allure of Hugo Chavez’s social revolutions. My presentation will connect the dots and matrixes of Jamaican social, political and musical movements, which continue to overtly and covertly revolutionize the world at large.

My understanding of revolution in Jamaican music and society, includes the social, political, cultural, technological and musical instances , events and artifacts that influenced, transformed.

Political Revolution: Socialism, Anti-Western and Colonial critiques, Slave Revolts

Social Revolution: Rasta, Ganja, Athletics, African Consciousness, Garrisons

Cultural and Sonic Revolution: Soundsystems, Dubplates, Versions, DJs, One Drop, Dubwise

My definition of revolution includes both the Marxist concept of addressing class struggle in society through direct actions, the anarchist concept of society organized through a consensus-based, decentralized, participatory model and simply revolution as a cultural expression of something unprecedented, innovative or transformative.

Jamaican music has always been based more in reality than escapist, fantasy or unrealistic notions. Like hip-hop, Jamaican music acts as a brutally honest mirror and reflection of the community at large often offering a moral, spiritual and political compass to those who follow it. Jamaican music, even its celebratory dancehall and rub-a-dub forms, employs sarcasm, humor, innuendo, plays-on-words, turns-of-phrases and other literary devices to explore and expose the good and bad in both politics and society. Contemporary Jamaican music and specifically reggae therefore has been the foundation of revolutionary movements and philosophies throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Jamaica as a nation has survived the eras of slavery, colonialism and finally self-rule with a proud tradition of resistance and resilience to everything from hurricanes and external economic convulsions, to gangland crime and poor infrastructure. Throughout, Jamaica’s citizens continue to trod innovative cultural and social paths that can only be summarized as revolutionary.

Reggae is a music of rude boys and rastas, powerful matrons and dancehall queens.

Jamaica stands as a singularly rebellious island nation, not driven to war by political aims, but, after 400 years of slavery, colonials and cold-war politics, seeking to establish a modern identity, while celebrating it’s deep music and cultural roots.

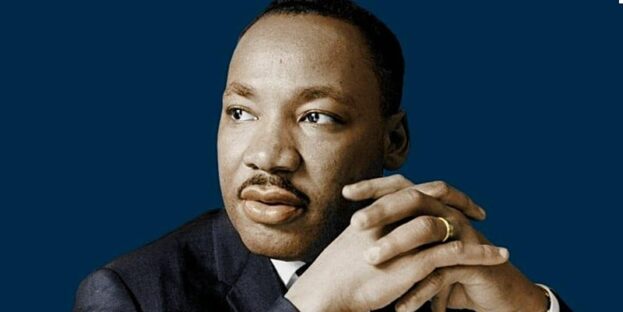

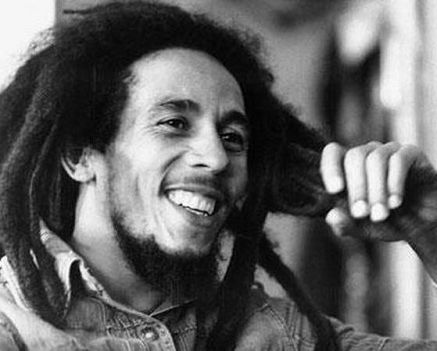

Martin Luther Kings said that we had to connect civil rights to human rights, specifically to poverty and ending war. Certainly Bob Marley realized this and echoed it in his song “War,” while quoting from Haile Selassie’s speech before the United Nations.

Martin Luther Kings said that we had to connect civil rights to human rights, specifically to poverty and ending war. Certainly Bob Marley realized this and echoed it in his song “War,” while quoting from Haile Selassie’s speech before the United Nations.

Jamaican music has always been a populist, decentralized, people-driven culture where marginalized points of view have been welcomed. (Explain)

A popular biblical phrase in Jamaica has always been “the stone that the builder refused, that turned into the head corner stone.,” which was sung in Bob Marley’s “Natty Dread Rides Again” on the album Survival.

Questions I posed to myself and others:

What makes Jamaica a revolutionary culture and society as compared to others? For instance, there are many island nations (Hawaii, New Zealand, Cape Verde, Madagascar, Japan, Ireland) that all have rich, cultural traditions.

What influence have external revolutionary movements played: Cuba, Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Angola (MPLA)?

Why is Jamaican music always been the first genre to respond to international wars, and express anti-war sentiments?

How have Jamaicans used technologies such as speaker boxes, sound systems, turntables and homemade electronics in a revolutionary way?

Is recycling “versions” a revolutionary concept? Did the concept of recycling riddims didn’t exist before reggae?

What about Rasta is revolutionary? The concept of rejecting an imposed Christianity for an African-centered spirituality, as well as championing marijuana as a natural healing and sacramental herb?

From Marcus Garvey to King Tubby, the concept of revolutionizing things is a constant thread in Jamaican society

Many of Jamaica’s National Heroes are revolutionaries or rebels: Nanny, Queen of the Maroons, Paul Bogle, Sam Sharpe, Marcus Garvey…

Reggae music gives body to Jamaica’s years of fighting of “Isms & Schisms”: Slavery, Colonialism, Capitalism

Jamaica is revolutionary in its self-reliance: Deciding that they don’t have to play hard to get American R&B singles, they can make their own music.

“This continuity, you get it in Jamaica, because music is a way of life. Because music is an earner of foreign capital. It is in fact the real natural resource in Jamaica — not tourism, not bauxite, not banana, not ganja, but music! Music is the key to Jamaica’s future development, in my opinion.” Steve Barrow (ReggaeNews.Co.UK)

According to Peter Mason’s In Focus: Jamaica (2000) ,reggae is Jamaica’s most recognizable and significant cultural asset (Mason, 63). It’s rhythm spread worldwide in the past five decades. It has been both a commercial and moral success, adopted by the dispossessed from Hopi Indian reservations in the US, to Brazilian slums and by the poor of many developing nations.

In 1972 when Michael Manley began unveiling his revolutionary socialism policies, which included anti-American and anti-Capitalist and anti-imperialist rhetoric, reggae was a perfect accompaniment. Manley enlisted the music of sympathetic artists including Max Romeo and Delroy Wilson to rally support and enshrine his legacy. Manley understood poor people music, and as only too happy to embrace it. Oddly, it was Manley’s chief political rival Edward Seaga who was actually more involved in music as owner of West Indies Records Limited (WIRL). He later sold his share to Byron Lee, who renamed the company Dynamic.

Manley’s socialist rhetoric worried the Americans who feared a Communist Caribbean, Latin and South America in their backyard, fueled by Cuban and Russian funding. An American backlash was inevitable. Weather it was guided by Henry Kissinger or not is debatable, but wherever you went in the developing world in the 1970s, from Viet Nam to the Congo, Kissinger’s political or philosophical influence was not far away. These counter-revolutionary measures from the West further fueled Jamaica’s grassroots revolutionary spirit, who saw allies in Tanzania, Mozambique and Angolan liberation movements, many of which were at least tacitly Communist backed. One specific music of this connection, reggae DJ and producer Tappa Zukie paid tribute to Angola’s successful freedom fighters by recording the ode “M.P.L.A.,” an adaptation of Little Richard’s “Freedom Blues.”

Rastafarianism can also be viewed as a revolutionary response to colonialism, slavery and imposed Western religious traditions. When Trinity recorded his mis-70s track “Pope Paul Dead And Gone,” welcoming the death of the long-serving and popular Roman Catholic leader, it came at the height of Rasta’s rejectionist period in which dreads had formed their own communes, dress and dietary codes that ran contrary to their colonial master’s traditions.

Rastafarianism had its roots in Marcus Garvey’s messages of self-determination and American black nationalism originating in Harlem in the 1930s (Barrow and Dalton, p. 144). Rastafarianism was established in Jamaica by Leonard Percival Howell in 1932, who established the Pinnacle community outside of Kingston.

Rasta we’re initially reviled and jailed through the 40s and 50s, but still managed to set up meeting quarters in the Back-O-Wall slum in Kingston. Rastas would increasingly assert influence in music and society as frustration grew with the post-colonial status quo.

In 1976 The Abyssinians recorded their monumental song “Declaration of Rights,” which codified Rasta’s revolutionary anti-colonial rhetoric with the lyrics:

Took us away from civilization

Brought us to slave in this big plantation

Fussing and fighting, among ourselves

Nothing to achieve this way, it’s worser than hell, I say

Get up and fight for your right, my brother

Get up and fight for your right, my sister

Two years later the Sex Pistols Johnny Rotten visited Jamaica to scout bands for Richard Branson’s Virgin Frontline series. Rotten and the Clash’s Joe Strummer acceptance and promotion of reggae in the early-70s solidified punk’s revolutionary brotherhood with Jamaican music. Punk musicians recognized reggae’s rebel spirit and attempted to find common ground.

Around this time Wayne Wade cut his black nationalist anthem “Stand Up And Fight” with Vivian Jackson, better known as Yabba You.

Throughout he late-70s friction arose between militant artists and their often white record company patrons, including Island’s Chris Blackwell and Virgin’s Branson. Artists including Tappa Zukie and Lee “Scratch” Perry questioned their business practices, and ties to white South African music distributors who fed into the Apartheid establishment. For many reggae artists, principal and black pride trumped business, a stance often misunderstood by white Western record producers and businessmen, many of whom still viewed reggae as an exotic tropical commodity, like sugar or rum. Hence, it’s easy to see how Rasta came sing songs critical of “bald heads,” code for unscrupulous Western capitalists.

Bob Marley was perceived as being a PNP supporter. He was shot in 1976, just before the Smile Jamaica concert. (Mason, p. 69) (insert Clive Chin comment). Marley left for two years, came back to Jamaica and performed at One Love concert and brought Michael Manley and Edward Seaga on stage. Marley celebrated Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 but died in May 21, 1981 from cancer.

In The Rough Guide To Reggae: Third Edition, author Steve Barrow, a former Trojan A&R and current A&R with Blood & Fire and Equalizer Music labels says that many Jamaican singers and musicians avoid publicizing their political sympathies, which is understandable in view of the violence that has accompanied elections (Barrow and Dalton, p. 111). Both the PNP and JLP frequently borrowed music for their campaigns with or without artists blessings. Hence, Delroy Wilson’s “Better Must Come” accompanied Manley’s victorious 1972 campaign. Manley had been dubbed Joshua after the biblical figure upon returning from a visit to Haile Selassie in Ethiopia in which the emperor had bestowed a white staff as a gift. Manley also used the music of Max Romeo (“Let The Power Fall For I”, “Joshua”), Junior Byles (“Joshua’s Desire”) and Clancey Eccles.

Clive Chin also recorded some artists who had explicated political themes in their music. But as Kingston began unraveling through the late-70s, political rhetoric in music became a deadly affair. Chin recalls talking to a member of the Heptones about that period and said, “I was talking to Earl Heptones the other day and he said, “Clive, I want to put out an anniversary album. You have a couple of tunes that I record and you probably never put out. I remember recording two political tunes and you never put them out.” And I told him, “You’re right.” But at the time, we could not involved with putting those kinds of songs out, because they were kind of a mark [on your reputation.] (4:48) That’s why a lot of artists [that recorded political songs] had to leave the island. You have guys like Ernie Smith who put out a song on Wildflower label called “Jah Kingdom Gone To Waste,” he had to leave right after that record was released. He went and lived in Canada.

“Max Romeo is another victim of that – [after recording songs like] “Three Blind Mice” – he had to come to the States. Mind you, I did a couple of social-themed and roots and culture songs along with Aston “Familyman” Barrett. But I had to keep them in the kitty (under wraps). In order for me to survive in the business, I had to record more [light-hearted, acceptable] tunes like “Ms. Wire Waist,” No Jestering” and “Fatty Boom Boom.” Those gimmick songs sold well but weren’t my cup of tea.”

Chin recalls other tunes of the time that weren’t as explicit but that used metaphors and double-meanings to get their message across: “Bob Marley’s] “Hypocrites,” [Peter Tosh] “Burial”, “Pound Get A Blow,” “Bust The Shut,” these were all social tunes. They weren’t identifying people by name, but you could read between the lines and get the meaning.”

Barrow’s Blood & Fire also reissued one of Max Romeo’s most political works, Revelation Time, in 1999 as Open The Iron Gate. When asked about it’s political significance Barrow said, “Even when the original copy of that album came out [as Revelation Time] it had hammer and sickle imagery on the cover. There’s a song on there (“Revelation Time”) where Max sings about the hammer and sickle. Max was a supporter of the Michael Manley PNP Socialist government of the time (1975), and his songs (“Joshua”) were used in Manley’s campaign. [Max’s music] was directly political. Max’s record dealt with some of the issues [Jamaica and the world} was going through. It dealt with politicians and people who promised one thing and couldn’t deliver. It even spelled out an end for the people who exploit people indiscriminately, he sang “Heads a go roll.”

But while some were predicting heads would roll, others attended to rolling tape, and the changes that new technology and original innovations with existing technology would bring to Jamaican music.

Technology Revolutions, Evolutions and Innovations

Clive Chin is son of Vinceny “Randy” Chin, a jukebox record supplier and owner of Randy’s Record Store and Randy’s Studio at 17 North Parade in Kingston. Clive Chin produced music at Randy’s in the early-70s before emigrating to the US where he started Jamaican restaurants before working with Patricia and Vincent’s VP Records.

As Clive Chin recalls: “During the early times, even with my father’s studio, the recording facilities were very limited. You would have to have all the musicians play at the same time the recording tape was on. If someone made a mistake, it had to be redone. It was all recorded on two track. Then it kind gradually went up to 4-track [reel-to-reel recording machines] in the late-60s.

“Coming into the 1970s now, talking about the experimenting with dub, and experimenting with instruments – I would call that the revolutionary period. You had producers now who came on board like Bunny “Striker” Lee, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Niney The Observer (Winston Holness), Clancy Eccles, Rupie Edwards…they set the ground work. What [King] Tubby’s used to do in the early-60s was build amplifier. But who really got him involved in the music was Bunny Lee. During [Tubby’s] period he could only really mix and voice, he couldn’t really record, because he didn’t have the facilities to record. So when dem record at Randy’s [studio], them go round Tubby’s and mix it.

Steve Barrow is a British reggae historian, writer and producer. In 1993 he co-founded Blood and Fire, a UK based record label specialized in reissuing older Jamaican music. In 2004, Barrow also co-founded another reggae reissue label, Hot Pot Music. Barrow has written several books on Jamaican music including The Rough Guide To Reggae.=

Steve Barrow saw the technological evolution as being a main contribution to the culture of “versioning” – using multiple mixes of the same basic rhythm track.

Barrow recalls of King Tubby: Through a combination of events and necessity, people [like Tubby] find out that with the multitrack or 2-track recordings you can use the track again, not only the original vocal, but you can use it for a different piece of music, something with a different melody on it, a different organ line, whatever.

“It was rapidly understood, that these riddims could be used three or four times. That was a revolutionary thing – but counter revolutionary from the musician’s point of view, because they weren’t needed for as many sessions. So the producer becomes much bigger, becomes like an author, or a mini-factory. These are situations that arose out of economic necessity in Jamaica at the time. The smaller producers reused tape a lot, that indicates that a lot of people were getting into the industry with limited resources. “

“That was revolutionary vis-à-vis the people who weren’t record producers before the advent of multitrack tape. They could make four riddims and make 16 songs out of that. They could sell that 16 times instead of four. So that enabled people to gain economic footholds. They didn’t even have to own a studio, they could go down to Coxsonne’s and rent time on a Sunday. It was democratic — everyone had some kind of access, or could align themselves with someone in their area — a local guy, a PNO activist, a don interested in developing talent in their area. “

Sonic and Social Innovations: DJs, Sound Systems

Ska took the world by storm in the years 1962-65. By 1966 dancers wanted a new beat and Duke Reid began producing the first rocksteady tunes to satisfy his audience. Heavily influenced by American doo-wop, soul and R&B balladeers such as The Impressions, Jamaican took on a pristine quality with each vocal group striving for more perfect harmonies than their competitors.

Steve Barrow sums up sound system evolution like this:

“A guy like King Edwards came along and made the biggest sound system set called King Edwards The Giant. Most sounds until then were little two-box affairs. And then there were only one or two sounds that had the dual [turntables] like V-Rocket Sound – he was the first one to use double decks so he could play one record after another for the people who wanted to dance without a break. That was revolutionary in that it replaced the band. From a musician’s point of view, it was counter-revolutionary because it put them out of a job.”

At the same time, in-part influenced by US southern and eastern radio disc jockeys, who were known for their catch phrases and song introductions, Jamaicans began DJing over instrumental versions of popular ska and rocksteady tunes in mis-60s. This evolution, later known as toasting, pre-dated American rapping by a decade, and stylistically propelled hip-hop. In fact, many East Coast emcees were Jamaicans who emigrated to the US or of Jamaican heritage (Pete Rock Heavy D, Kool Herc), adapting their home sound system culture and merging it with the funk, disco and spoken word idioms to create early rap and hip-hop.

Jamaican sound systems themselves from their inception were revolutionary, in that they brought music to communities who couldn’t otherwise afford entertainment. They were multigenerational events with young and old mingling, dancing and exchanging information. They recognized the importance of music as a daily function, and cultural necessity rather than a rarified commodity. In short, the sound system dance was a communal music expression that harkens back to African ritual and celebratory music. But political and social changes caused further changes and upheaval in sound as modern Jamaican music entered it’s fourth decade.

Steve Barrow describes the explicit political connections some sound systems maintained: “When the world economic crisis hit in the 1970s, the veil is stripped from their eyes, so they look for other solutions and you get the rise of Rasta. You’ve got [King] Tubby, out of necessity an lack of certain materials, has made this whole sound system thing much bigger than it was in the 1950s. So much so that the DJ thing that developed alongside of it became a partisan political thing as well. You get certain sounds that only play for certain political parties. Like Socialist Roots. “

DJs like Nicodemus, Ranking Trevor got their start on Socialist Roots.

Barrow continues, “I know a lot about [Socialist Roots] from mixing all these years with U-Brown, who was there as it happened. And U-Roy as well said the same thing. Socialist Roots was originally called King Attorney, which got sold to Tony Welch, a PNP activist who wanted to keep some dances. These dances were also just dances where you could “forget your troubles and dance” (Bob Marley) – but don’t forget your politics! You could go [to a politically-backed sound system dance] and show your support by licking off two shot for the PNP man or the JLP man. [These dances] became social theater.”

The cost of living rose shot up between 1983 and 1989. (Hope, p. 5) By 1993, 28 percent of the population lived below the poverty line, with a peak of 37 percent in1989. Unemployment hovers around 18 percent. A depreciation for the poorer classes in public health, education with a contraction of employment and housing lead to increased social tension, soaring murder rates and more focused political expressions in reggae music. DJ Panhead, an ardent critic of corruption and government fell victim to the violence in 1993. He was quoted in Reggae Island (Jahn and Weber, De Capo 1993) as saying “Dancehall is the roots music now”

Many dancehall artists, including Capleton, Buju Banton and Spragga Benz began their careers promoting slack, sexual lyrics, only to transform into devout rastas and political critics later in their career. Reggae artists and DJs in particular realized that when talking politics became too dangerous, talking sex, although taboo, was as powerful and rebellious. Jamaican DJs became renown for their sexually explicit slang and metaphors, so much so, that the word “punnany” is now a universally understood term for female genitalia.

Female artists like Lady Saw, Ce’Cile and Tanya Stephens joined in the rebellion against conservative social mores by often being more lyrically sexually explicit than their male counterparts. The risk paid off with many of these artists becoming both commercially successful, building strong male and female fan-bases while expressing a strong, confident sexuality that was neither submissive nor placating male machismo dictates. Similarly, the emerging dancehall queen dance competitions rely heavily on strong, individualistic and sexually-charged routines that combine acrobatics with freestyle dances. In this arena, women have become fashion warriors with elaborate one-off costume and outfits, and their dances make as much of an aggressive, battle-ready statement as male selectors do with their dubplates.

Although, until very recently, with the rise of artists like Queen Ifrica, Etana, Tanya Stephens and Alaine, participation for women in reggae music recording has been inhibited by Jamaica’s male-dominated entertainment industry, women have contributed equally to the growth and vibrancy of the music. As the works of Judy Mowatt, Marcia Griffiths, Sister Nancy, Sister Carol and Althea & Donna illustrate, reggae has the potential for democratic participation and equal status among the genders. These egalitarian notions hint at the greater international appeal Jamaican music and culture has achieved.

Conclusions

Producer and singer Roy Cousins told author David Katz in his book Solid Foundation: An Oral History of Reggae Music (Bloomsbury), “If you listen to reggae music, you don’t need to buy the paper. Reggae tell you everything wha’ happen in Jamaica.”

Jamaica’s culture and music has touched the world in large and also subtle ways. As Clive Chin notes, “It’s not only the music that has had an effect on global culture, I see it in the way of life, in our athletics – we’re very good in sprints, we’ve gotten medals in the Olympics. The governor of New York, David Patterson, one of his parents is from Jamaica.

I think because of where we come from, from slavery, British colonialism, we tend to express our feelings and whole heart into the music. Apart from that, it was a perfect time I believe, that we opened the door to the world that, as small as we are as an island, we tend to express it in a very in-depth and very social way that the people of the world accept what we have to offer and what we had.

It makes sense that Jamaica’s universal ideals and music would cross borders and unite people globally. After all, the island’s motto is: Out of Many One People. And as Chin concluded, “At the end of the day is all of we that eat out of one pot.”

40 Years of Revolutionary Jamaican Music Top Five:

- Skatalites “Independent Anniversary Ska” (1966)

Rasta influenced ska; the band played odes to political events” “Lee Oswald,” “President Kennedy,” “Cuban Blockade,” “Nanny’s Corner”

- King Tubby “Dub To The Rescue” (1976)

A sound master, engineer, mixer, dub revolutionary.

Also: Tapper Zukie “M.P.L.A.” Inspired by Angola’s Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (1975-present)

- Dennis Brown “Revolution” (1986)

A gentle prophet and romantic singer, sang everything from sufferers anthems like “Tenement Yard,” to unity tunes like “Here I Come.” “Revolution” lyrics: “Do you know what it means to have a revolution, and what it takes to make a solution? Fighting against down-pression, battering down depression. Are ready to stand up and fight the right revolution? Are ready to stand up and fight just like soldiers? Many are called, few are chosen.

Also: Admiral Bailey “Politicians” A king Jammy$ dancehall classic with a social message.

- Anthony B “Fire Pon Rome” (1996)

Also: Bounty Killer “Fed Up” One of the mid-90s most explosive sufferers anthems, aiming squarely at politicians.

- Vybz Kartel Mr. Politician (2006)

Also: Chuck Fender Freedom of Speech

Other Jamaican revolutionary songs: (with apologies for leaving off Bob Marley, LKJ, Steel Pulse and British reggae in general)

Viceroys “The Struggle” (1974/5)

“Mama, oh mama, please don’t vex with I. We’ve got to sit down and reason. These are not the days when you were a youth, and you had to live on the Capitalism rule. In a the struggle too. Equal rights and justice for everyone,.”

Delroy Wilson “Better Must Come” (1970)

Used by Michael Manley in his 1976 reelection campaign.

Ronnie Davis “False Leaders”

“We’re a righteous people, we need righteous leaders, too long we’ve been living in captivity.”

Anthony B “Fire Come Now” (1996)

“Fire come now, and them bone gwine fry, who a work for CIA and FBI – dem a spy!”

Edi Fitzroy “First Class Citizen”

Heptones “Sufferers Time” w/Lee Perry

Freddy McGregor “Revolutionist”

Earl Zero “Shackles & Chains”

Rod Taylor “Ethiopian Kings”

Mighty Diamonds “Right Time”

Michael Prophet “Mash Down Rome”

Big Youth “Political Confusion”

Pablo Moses “We Should Be In Angola”

Max Romeo “War Ina Babylon”

Jah Lion “Soldier and Police War”

Trinity “Pope Paul Dead & Gone”

Yabby You “Pound Get A Blow” ““Blood A Go Run Down King Street”

Burning Spear “Marcus Garvey” and “The Invasion”

Junior Delgado “Sons Of Slaves”

Richie Spice “Open The Door”

Pan Head “Under Bondage” & “Poor People Government” (1966 – 1993)

Cocoa Tea “Obama”

Bob Andy “Unchained”

Black Uhuru “Whole World is Africa” & “Bull In The Pen”

Johnny Clarke “Never Love Poor Marcus,” “African People,” “Roots Natty”

Wayne Wade & Yabby U “Stand Up & Fight”

Richie Spice “Operation Kingfish”

Alborosie “Herbalist”

Tarrus Riley “Pretect Yu Neck”

King Tubby And Friends “No Love Version” and “Away With The Bad”

Morwell Limited Meets King Tubby’s “Lightning & Thunder”

Augustus Pablo “Stop Them Jah”

Political artists:

Peter Tosh

Dennis Brown

Bounty Killer

Mutabaruka

Michael Smith

Lee Scratch Perry

Sizzla

Tanya Stephens

Richie Spice

Johnny Clarke

Morgan Heritage

Judy Mowatt

Anthony B

Culture

Tony Rebel

Louie Culture

Mighty Diamonds

Cultural Roots

Jr. Delgado

Damien Jr. Gong Marley “Welcome To Jamrock”

http://forwardever.blogspot.com/2004/12/welcome-to-jamrock-2004s-best-reggae.html

The best reggae song of 2004 is undoubtedly Damien “Jr. Gong” Marley’s “Welcome To Jamrock” (Ghetto Youths). Toasting rapid-fire over a sample of Ini Kamoze’s 1984 track “World A Reggae” (produced by Sly & Robbie), Marley depicts the side of Jamaica that tourists rarely see. Like his father before him, Marley is at his best when he’s telling it like it is. The lyrics, which you can read below, take you CNN-style to battleground Kingston, with vivid images of the dark side of a thug life fueled by poverty, roadblocks set up by police and the poor alike, and the idle promises of politicians.

To put the song in context, as of Oct. 3, 2004, the Jamaican Gleaner reported that the murder rate for the year was 1,030 persons (in a country with a population of 2.5 million). The week before Hurricane Ivan struck, 34 died in a seven-day period, the storm reported killed 37. Jamaica has the fourth highest crime rate per capita behind Russia, Brazil and Colombia. Clearly, even the son of an icon is not immune to the community’s tensions, and Damien has found an adept voice to characterize his nation’s plight.

When Bob Marley sang “every man have a right to decide him own destiny” (“Zimbabwe”) in 1979, few in the West were thinking about the struggles for self-determination taking place against a backdrop of the Cold War in Africa. At the time, America supported apartheid in South Africa and the CIA was fighting proxy wars across the continent. So when Bob sang, “Soon we’ll find out who is the real revolutionaries, and I don’t want my people to be tricked by mercenaries” he was invoking the kind of veiled leftist rhetoric that had Jamaica’s Michael Manley-PNP (Peoples National Party) government economically blacklisted until a regime change swept Edward Seaga to power shortly after Reagan was elected in the US. Bob Marley (having been nearly assassinated in 1976 before a peace concert) walked a tightrope, commenting on politics in Jamaica and abroad; topics that Damien seems to have comfortably adopted.

Unlike his singing siblings, Damien “Jr. Gong” took a different path, becoming a conscious Rasta DJ in the style of Capleton or Anthony B. His militant wails come closest to his father’s passion, although some would argue that Damien’s brother Ziggy sings the most pitch-perfect. But unlike Ziggy’s watered-down, flowerchild odes, Damien’s music is ardent and forthright; a staple not lost on “Jamrock”’s growing audience.

In the past two months the track has quickly become a staple at dancehalls in San Francisco, and is both the most re-wound track at local club nights Bless Up (Milk Bar) and Give Thanks (Club Six), as well as the top selling single at Wisdom Records. Interestingly, this is the first time in a while that San Francisco actually launched a track to a greater global status, beating even London (where its currently #3 on BBC 1Xtra’s chart) and New York to the punch. So while other massives were dancing to “Father Elephant,” longing for the imprisoned Jah Cure or burning Babylon with Sizzla, “Welcome To Jamrock” quietly ascended to a higher level. And when you hear it, you’ll overstand what I mean.

Intro: (Sample of Ini Kamoze)

“Out in the streets, they call it murder!”

Verse 1:

Welcome to Jamrock, camp where di thugs dem camp at

Two pound a weed inna van bag

It inna yuh hand bag, yuh knapsack it inna yuh back pack

Di smell a give yuh girlfriend contact

Some bwoy nah notice, dem only come around like tourist

On di beach wid a few club sodas

Bedtime stories, and pose like dem name Chuck Norris

And don’t know di real hardcore

Cause Sandals a nah back too, di thugs dem weh do weh dem got to

And won’t tink twice to shot yuh

Don’t mek dem spot yuh, unless yuh carry guns a lot too

A pure tuff tings come at yuh

When Trenchtown man stop laugh and block-off traffic

Then dem wheel and pop off and dem start clap it

Wid di pin file dung and it a beat drop it

Police come inna jeep and dem caan stop it

Some seh dem a playboy (dem) a playboy rabbit

Funnyman a get dropped like a bad habit

So nuh bodda pose tuff if yuh don’t have it

Rastafari stands alone!

Chorus:

(*Bounty Killa sample)

Welcome to Jamrock, Welcome to Jamrock

(Ini Kamoze sample)

“Out in the streets, they call it murder!”)

Verse 2:

Welcome to Jamdown, poor people a dead at random

Political violence cyaan dun

Pure ghost and phantom, di yute dem get blind by stardom

Now di Kings Of Kings a call

Old man to pickney, so wave oonu hand if yuh wid mi

To see di sufferation sick mi

Dem suit nuh fit mi, to win election dem trick we

They they don’t do nuttin at all

Come on let’s face it, a ghetto education’s basic

A most a di yutes dem waste it

And when dem waste it, dat’s when they tek di guns replace it

Then dem don’t stand a chance at all

And dat’s why a nuff likkle yute have up some fat matic

Wid di extra magazine inna dem back pocket

And have leisure night time inna some black jacket

All who nah lock glocks a dem a lock rocket

Then will full yuh up a current like a short circuit

Dem a run a roadblock which part di cops block it

And from now till a mornin nuh stop clock it

If dem run outta rounds a brought back ratchet

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Barrow, Steve and Dalton, Peter, (2004) The Rough Guide To Reggae: Third Edition, Rough Guides Ltd, London, England

Hope, Donna P., Inna Di Dancehall: Popular Culture and The Politics of Identity in Jamaica, (2006), University of West Indies Press, Kingston, Jamaica

Jahn, Brian and Weber, Tom (1992)Reggae Island, Kingston Publishers, Kingston, Jamaica

Mason, Peter, Jamaica In Focus (2000) Interlink, Brooklyn, NY

Tomas Palermo

San Francisco author, editor and DJ Tomas Palermo is the former editor of XLR8R Magazine (1999 – 2005). From 1990 to the present, Palermo contributed to Urb, The San Francisco Bay Guardian, Riddim, Sleaze Nation and Earplug.cc,. Palermo began DJing in high school at a 10-watt FM station playing reggae and punk, and continues to this day at KUSF, 90.3 FM in San Francisco. Palermo edits the progressive webzine WireTapMag.org, contributes three weekly columns to XLR8R.com and updates his ForwardEver blog.

Thanks to Steve Barrow, Clive Chin, Stephen David, David Katz, Dr. Carolyn Cooper, Norman Stolzkoff, Stephanie Black, Ms. Lou, and all the singers and players of Jamaican music.

This presentation is a meditation on Jamaica as a revolutionary culture and nation. It’s a reflection on five decades music with explicit and subtle political and social revolutionary message. It’s a dedication to a country that embodies resistance to colonialism, wanton Capitalism and religious power. This is my livication to revolutionary Jamaican music, culture, politics and people.

For this presentation I researched multiple sources and conducted phone interviews with Blood & Fire A&R man Steve Barrow and record producer Clive Chin.

Many of the political and cultural threads I will discus have been explored throughout reggae’s development, most prominently in Stephen Davis’s 1977 work Reggae Bloodlines, as well as in the BBC Channel 4 documentary series Deep Roots Music and the liner notes of countless album releases. However, these ideas warrant review in this new century, 46 years after Jamaica gained independence from the Britain.

My mission, thus, is to consider the macro elements of Jamaica popular resistance through music and culture – how its all tied together — rather than the equally important micro studies on specific topics such as the Caribbean’s economic structure, Bob Marley’s transnational appeal or Mutabaruka and Linton Kwesi Johnson revolutionary dub poetry. Instead, join me on this reflection on the global aftershocks resulting from the earthquake, lightning and thunder that is Jamaican music.