In January 1846, Frederick Douglass arrived in Scotland as a man who was both internationally recognised and legally vulnerable. His autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, published in 1845, had exposed the realities of American slavery with extraordinary clarity. It had also made him identifiable under United States law. Though celebrated abroad, he remained a fugitive.

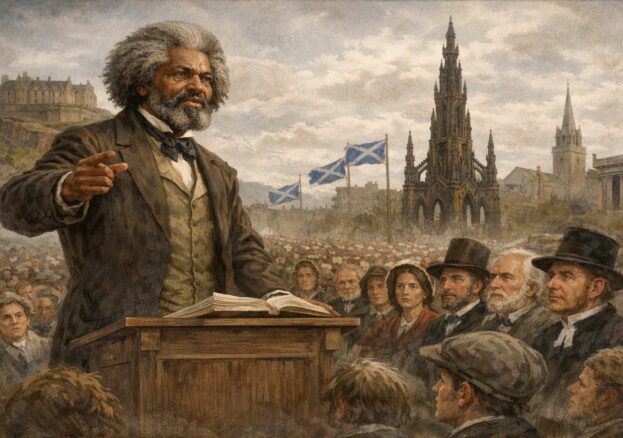

For nearly two years, from 1845 to 1847, Douglass travelled across Britain and Ireland. Scotland proved one of the most politically significant stages of that journey. Here, he did more than recount the brutality of enslavement. He challenged audiences to consider their own nation’s entanglement with slavery and its profits. In doing so, he reshaped both his own political future and Scotland’s understanding of its place in the Atlantic world.

From Enslavement to International Advocate

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland in 1818. Like many enslaved children, he was separated from his mother at an early age and denied formal education. He later described how learning to read became a turning point in his intellectual development, despite the violent resistance of slaveholders who understood that literacy threatened control.

After escaping in 1838, Douglass settled in the northern United States and became active in the abolitionist movement. His powerful oratory quickly attracted attention. Yet in his early years as a speaker, even sympathetic white abolitionists sometimes framed him primarily as living testimony — evidence of slavery’s cruelty — rather than as a political thinker.

The publication of his Narrative in 1845 altered that dynamic. The book was a bestseller, widely read in both America and Britain. It established Douglass not only as a witness to slavery but as a writer of considerable skill and authority. At the same time, by naming former enslavers and locations, it increased the risk of his recapture. Advisers encouraged him to travel abroad.

Scotland and the Atlantic Economy

When Douglass arrived in Scotland in early 1846, he entered a society that prided itself on moral seriousness and intellectual life. Churches, debating societies and reform groups were central to public culture. Many Scots had supported the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833.

Yet Scotland was not removed from slavery’s economic foundations. Glasgow’s eighteenth-century wealth had been built in part on tobacco grown by enslaved labour in the American colonies. Scottish merchants invested in Caribbean plantations, and industrial expansion in Britain depended heavily on slave-produced cotton from the American South. Financial, commercial and cultural links tied Scotland to the wider imperial economy.

Douglass understood this clearly. As he lectured in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee, Perth and Aberdeen, he spoke not of a distant American problem but of a global system in which Britain was implicated. His speeches connected plantation labour to industrial prosperity, challenging audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about economic interdependence.

The “Send Back the Money” Campaign

One of the most significant episodes of Douglass’s Scottish tour was his involvement in the “Send Back the Money” campaign. The controversy centred on the Free Church of Scotland, which had accepted donations from slaveholders in the United States during a fundraising visit in 1844.

Douglass and fellow abolitionists argued that a church could not condemn slavery while retaining funds derived from it. The slogan “Send Back the Money” became a rallying cry at public meetings across Scotland. The campaign provoked heated debate within religious communities and in the press.

For Douglass, the issue was one of moral consistency. If slavery was a sin, its profits could not be sanctified by religious purpose. His insistence on this point revealed how deeply slavery’s proceeds travelled — across the Atlantic and into respected institutions.

Experiencing a Different Social Climate

Amid political controversy, Douglass also experienced something personally transformative. In Scotland, he could move through public spaces without the immediate threat of being seized as property. He stayed with supporters, dined with reformers and addressed large audiences who engaged seriously with his arguments.

He later reflected that in Scotland he was treated “not as a colour, but as a man”. The phrase was not a claim that prejudice was absent in Britain. Rather, it captured the contrast with the legally enforced racial hierarchy of the United States. There were no slave patrols, no fugitive slave laws, no system defining him as property.

This experience reinforced a crucial realisation: racial subordination was not inevitable. It was constructed through law, violence and custom — and therefore could be dismantled.

Securing Legal Freedom and Political Independence

During his nineteen-month tour of Britain and Ireland, Douglass’s reputation grew substantially. Supporters in Britain raised £150 in 1846 to purchase his legal freedom from his former enslaver, Thomas Auld. Although Douglass felt uneasy about the symbolism of buying his own liberty, the arrangement ensured that he could return to the United States without risk of recapture.

His time abroad also strengthened his independence within the abolitionist movement. Encouraged by supporters he met in Britain, Douglass determined to establish his own newspaper. In December 1847, shortly after returning to the United States, he founded The North Star in Rochester, New York. The paper became an influential platform for abolition, civil rights and women’s suffrage.

Scotland, therefore, was not simply a safe haven. It was a place where Douglass consolidated his intellectual autonomy and international authority.

Scotland’s Response and Historical Significance

Scottish newspapers covered Douglass’s lectures extensively. While reactions varied, his presence stimulated sustained public debate. He challenged assumptions of British moral superiority and highlighted the continuing economic ties between Britain and slave labour abroad.

Although his visit did not transform Scottish policy, it sharpened awareness and deepened anti-slavery activism. More broadly, it demonstrated that Black political leadership was central to nineteenth-century reform movements, not peripheral to them.

Douglass returned to the United States in 1847 strengthened by his experiences overseas. Over the following decades he became one of the most influential figures of the nineteenth century — advising presidents, advocating for Black citizenship during Reconstruction, and campaigning for women’s rights.

Scotland remained a significant chapter in his life story. It was where he experienced public recognition without legal vulnerability, and where he refined the international dimension of his political vision.

His time there reminds us that slavery was never solely an American story. It was part of a shared Atlantic system linking plantations, ports, factories and churches. Douglass insisted that moral responsibility travelled along those same routes.

He did not come to Scotland seeking celebration. He came to argue for consistency between principle and practice. In listening — sometimes defensively, often thoughtfully — Scotland became part of a wider movement that would, within two decades, see slavery abolished in the United States.

References and Further Reading

- Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. Simon & Schuster, 2018.

- Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. 1845.

- Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. 1855.

- Devine, T. M. Scotland’s Empire, 1600–1815. Penguin, 2004.

- Mullen, Stephen. “Frederick Douglass in Scotland.” University of Glasgow research materials.

- National Library of Scotland. Collections relating to Douglass’s 1846 lecture tour.