Picked in 1925, Jack Leslie would have been the first black player to play for England, 53 years before Viv Anderson.

By the time he died, in 1988 at the age of 88, there were many more black players at top levels of the game.

Leslie was born in Canning Town, in London’s docklands, in 1900, to an English mother and a Jamaican father.

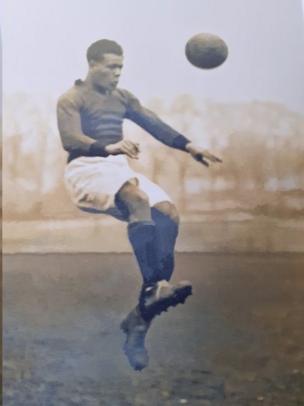

A gifted athlete, he played for Barking Town, where his prolific scoring record attracted the attention of Plymouth Argyle, then a third-division club.

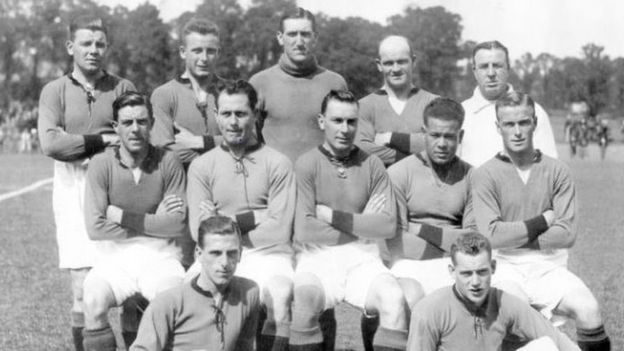

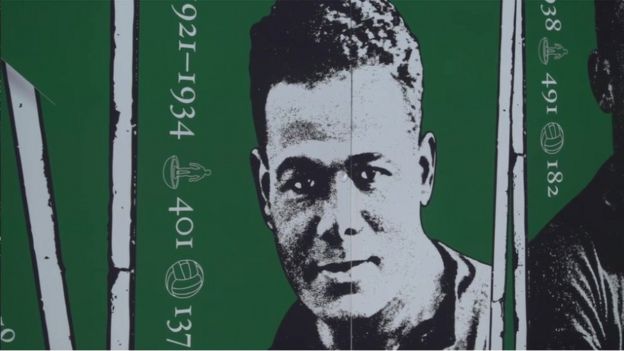

He joined them in the 1921-22 season and stayed for 14 years, making 401 appearances and scoring 137 goals, a feat made all the more impressive because of the racial abuse he experienced at the hands of both crowds and opponents.

He is remembered as a great attacking inside left but also a utility player who could fill in as a central defender.

England call-up

In 1925, Argyle’s manager, Bob Jack, called his star striker into his office and gave him some thrilling news – Jack Leslie had been selected to play for England against Ireland.

It was a great achievement for the player and an honour for third-division Plymouth.

His selection was the talk of the club and the town – but some days later, when the newspapers published the team, Billy Walker, of Aston Villa, was in the starting line-up and Leslie was named as a travelling reserve.

He never did travel with the England team to Belfast.

Instead, while England struggled to a 0-0 draw, he scored twice, as Plymouth trounced Bournemouth 7-2 at home.

“I believe that the manager sent in his request, saying: ‘I’ve got a brilliant player here, he should play for England,'” his granddaughter, Lesley Hiscott, said.

“So then someone came down to watch him.

“They weren’t watching his football.

“They were looking at the colour of his skin.

“And because of that, he was denied the chance of playing for his country.”

Leslie later suggested finding out he was black, for the selectors, must have been “like finding out I was foreign”.

But he accepted what had happened and, according to his granddaughters, never expressed any bitterness.

They remember him as a kind and loving grandfather.

He had married their grandmother, Lavinia, in 1925, at a time when it was unusual for a black man to marry a white woman.

And as a consequence, some of the family, and Lavinia in particular, experienced racial abuse.

Lyn Davies said: “If I walked down the street with my friends and he was coming the other way, he would cross to the other side of the road so I could pretend that I didn’t know him, so I didn’t suffer.

“But I’d run across and say, ‘Hello Granddad.'”

Despite helping Plymouth gain promotion, a top-four finish in division two, captaining the club and, in 1931-32, scoring 21 goals in 43 games, Leslie was never again picked for England.

Anderson, picked to play for England against Czechoslovakia at Wembley in 1978, went on to win 30 caps.

“I’d never heard of Jack Leslie until up to two weeks ago,” he told BBC News.

“And that’s a crying shame, because what he achieved and what he did should be paramount in every black person’s mind.

“It’s a crying shame but hopefully the statue they are trying to get erected will carry on his legacy.”

Argyle have already honoured Leslie with a mural and renamed their boardroom after him.

And now a group of fans are campaigning for a statue.

“At a time when some statues are being pulled down, we want to put one of Jack Leslie up to commemorate his amazing achievements and to remember the injustice that he suffered,” campaign co-founder Greg Foxsmith says

The campaign hopes to raise £100,000.

And supporters include Anderson and the club itself.

“Having a statue promoted by our fans and funded by fans is a statement by them that they are joining the fight against racism in football,” Plymouth chairman Simon Hallett told BBC News.

“History has been written by the winners and I think we are now trying to pay more attention to some of the victims of those victories.”

Bill Hern co-author of the upcoming book Football’s Black Pioneers said: “Jack Leslie should have been a major figure in the history of British football and society.

Bill Hern co-author of the upcoming book Football’s Black Pioneers said: “Jack Leslie should have been a major figure in the history of British football and society.

“Everyone needs a role model and young black footballers didn’t have that major role model in the 30s, 40s and 50s.

“Had he played for England, as he should have, he would have fired the aspirations of generations of young black players.”

Boot room

Leslie’s playing days came to an end after he sustained an injury when a lace from a leather ball flew into his eye.

He and his family returned to east London and he resumed his trade as a boilermaker

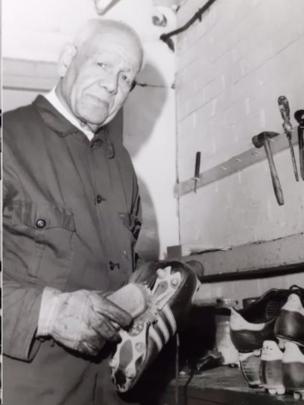

Following his retirement and with time on his hands, Lavinia urged him to go to West Ham and ask the club if there was any work he could do.

He met manager Ron Greenwood, who immediately recognised and remembered him as a great player.

Greenwood offered him a job in the boot room, where, somewhat poignantly, he cleaned mud from the boots of England stars Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst, Martin Peters, and Trevor Brooking.

Greenwood offered him a job in the boot room, where, somewhat poignantly, he cleaned mud from the boots of England stars Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst, Martin Peters, and Trevor Brooking.

In a further ironic twist to his story, Leslie also cleaned the boots of West Ham’s black striker Clyde Best, who, in the late 1960s and 1970s, was still one of only a tiny number of black players in top-flight English football.

Leslie loved the work and being around footballers but it was hardly fitting for a man who should have occupied a unique place in football history – and now, perhaps, will.

“Stories like this are incredibly sad. Discrimination in the game, in any form or from any time period, is unacceptable,” said FA chairman Greg Clarke, adding that English football had made “huge strides” in diversity, although there was still more to do.

He said the FA backed the campaign for a statue to recognise Leslie as a pioneer.